Also, in the spirit of TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY, I’ll be running a gallery of folk horror on film, but specifically picking movies that are perhaps less well known or less associated with that genre.

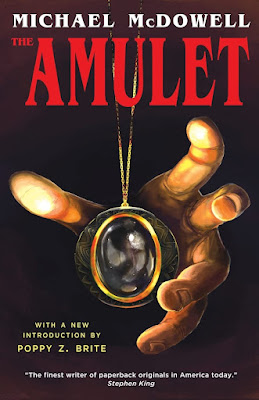

While we’re on the subject of rural horror, I’ll also be offering a detailed review of the late Michael McDowell’s 1979 classic, THE AMULET.

If you’re only here for the McDowell review, that’s A-okay as always. Just hop straight down to the Thrillers, Chillers section of today’s blogpost, and you’ll find it there.

Before then, however, let’s get back into the world of …

Terror Tales

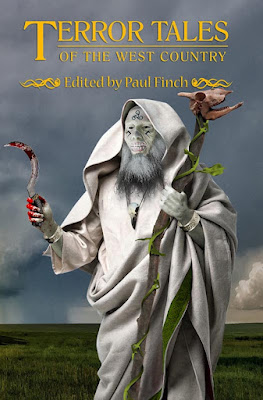

TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY is the 14th in the TERROR TALES series. For anyone who hasn’t encountered these books yet, they are a series of folklore-based horror anthologies, each one set in a different geographic region. They comprise both fiction (mostly original and from some of the best ghost and horror writers in the field) and snippet-length ‘true terror’ anecdotes.

TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY kind of speaks for itself. It’s all about England’s mystical West Country. I don’t think I need to say too much more about that. Anyway, the amazing Ro Pardoe of GHOST AND SCHOLARS fame has finally cast her discerning eye over it, and on the whole seems to approve. I hope she won’t mind if I include a few quotes from her, as we work through her various high points.

Ro heaped praise on the ‘incredibly impressive’ line-up and, in no particular order of preference, singled out a number of specific stories for praise, including Dan Coxon’s The Darkness Below, which she likens to Ramsey Campbell at his best, and summarises as ‘when a family visits Gough’s Cave at Cheddar Gorge, are they the same people who come out, and if not, which of them has changed?’ She also mentions Lisa Tuttle’s Objects in Dreams May Be Closer Than They Appear, which she calls ‘a fine tale of nightmarish time entrapments, and a Devon house visible on Google Satellite View which is almost impossible to find on the ground (it would have been better for the narrator if it had been completely impossible to find).’

Inevitably, Ro, an expert on MR James, is exceedingly fond of the volume’s antiquarian stories. Of John Linwood Grant’s The Woden Jug, she writes ‘in Somerset, an apparent stoneware witch-bottle, decorated with a one-eyed face, turns out to be a protection not against witches but against something else entirely’, and calls it ‘a good one’. Ro wastes few words when she likes something, so this is praise indeed.

Another antiquarian tale she enjoyed was Stephen Volk’s Unrecovered, which she says stands out in the volume, adding ‘it begins in familiar territory, with the archaeological excavation of a Wiltshire Anglo-Saxon cemetery, and the sighting of a distant figure with only half a head … but the horror is of a more recent war and the trauma of losing a buddy on the battlefield. I can’t deny that I shed a tear’.

There are three main Dartmoor-set stories in the anthology, an ancient landscape that has proved a happy hunting ground for horror writers going way back, and Ro seems to have particularly enjoyed these. She was pleased that in Thana Niveau’s Epiphyte, ‘the supernatural threat takes an unusual form’, and says of Adrian Cole’s Land of Thunder that ‘a horrific episode in the history of Dartmoor jail produces revenants raised by a much older force on the moor’. But above all, the story she considers the best in the book, is Steve Duffy’s Certain Death for a Known Person. Those who don’t know Steve Duffy’s work need to rectify that, as he’s an author of exceptional skill. Of his story here, Ro writes, ‘I don’t know many authors who could turn what is essentially a Twilight Zone-type plot about Death personified, and an agonising choice that needs to be made into something as introspective and deep’.

As for own contribution, Bullbeggar Walk, which is ‘set on Exmoor, where a church’s stained glass window provides a vivid depiction of the legendary Bullbeggar, a monster created through a disagreement between an Anglo-Saxon and a Norman in the 11the century,’ Ro describes it as ‘effective’.

Well … I told you that she doesn’t waste words.

Secretly, I’m most pleased that Ro likes and appreciates how much time and effort went into my own creation of the anecdotal ‘true’ stories that intersperse the works of fiction. These are great fun but time-consuming to research and write. For the most part, reviewers seem to appreciate them, but Ro says of them that they ‘are among the highlights of the book’.

Anyway, the overall review is far more extensive than I’ve quoted here. If you want to read it in full, you’ll need to get hold of Ghosts & Scholars 44. However, I’d like to thank Rosemary for taking the time and trouble to offer her opinions and provide us with what amounts to a detailed, fulsome and very warm-hearted review of the latest book in the series.

(In an item of late news, I can also reveal that TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY will also be reviewed today, Sunday May 21, on BIG HIT RADIO on Trevor Kennedy’s noon programme).

On the subject of TERROR TALES, a few quick words now about the next one in the series, which will be TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN. You may consider that an unusual break-away from our more normal British-set volumes, and it probably is, but I’d draw your attention to the fact that we did TERROR TALES OF THE OCEAN in 2015, which obviously wasn’t British-bound, and maybe was a sign of things to come. After all, in the next two or three years, we’ll have run out of locations in mainland Britain. We opted to visit the Med this time around, with one or two UK locations still remaining, just to freshen things up a little and to check out the lie of the and where our readers are concerned.

I beg no one to entertain even the remotest possibility that this location might not ‘do it for them’ in horror terms. Already, and the book is nowhere near ready yet, we’ve found some visceral terror in the secretive halls of Turin’s satanist university, in the Spanish/Pyrenean castle where a decadent and brutal vampire lurked, and among the mist-shrouded origins of some of that ancient region’s most terrifying monsters … among many others.

And now, just for the hell of it, let’s check out a gallery of …

Lesser known folk horror

While we’re on the subject of folk horror, and also because I love this stuff so much, here’s a fun list. Folk horror(ish) movies you might not have heard of but ought to watch at least once. The first rule I’m imposing is that none of these films have got status as classics of folk horror, so that means no The Wicker Man, no Blood on Satan’s Claw, no Witchfinder General, no Midsommar, no The Witch. Second rule, none of these are British in origin, as it’s surely about time we looked beyond the borders of folk horror’s traditional home, which means no Kill List, no Night of the Eagle and no A Field in England.

With luck, that doesn’t mean that you won’t enjoy it. So, in the order of their production, let’s get cracking.

HAXAN (1922)

Dramatised but scholarly narrative, following the emergence of witchcraft as a potent force, from the early days of village ritual to the publication of Malleus Maleficarum and the violence of the Inquisition. Ben Christensen writes, directs and stars in this hotchpotch of pagan / Satanic / psychological horror, which was highly controversial for its depictions of nudity and torture.

CITY OF THE DEAD (1960)

The search for a missing student leads two guys through mist-shrouded Massachusetts to the eerily olde worlde village of Whitewood. At first glance, a traditional witchcraft chiller, but with lots of neat folky touches: the Hour of Thirteen, the silent dancers etc. An early pre-Amicus effort for Milton Subotsky, with Chris Lee nailing himself down as horror’s primary villain.

THE HAUNTED PALACE (1963)

Newly married heir to a fortune, Charles Dexter Ward returns home to New England, to find deformed villagers everywhere, and his mansion-like residence the centre of a cult bent on summoning ancient powers to create an evil super race. HP Lovecraft gets in on the folk-horror act, Corman directs, Vincent Price and Lon Chaney Junior star. What more could you want?

KWAIDAN (1964)

Horror abounds in this early, excellent portmanteau of Japanese folk tales, all adapted from the works of Lafcadio Hearn, including terrifying stories like Black Hair (which became go-to Japanese horror) and Woman of the Snow. Masaki Kobayashi directs while Yoko Mizuki scripts, the pair managing what had previously been thought impossible: bringing Japanese mysticism to western audiences.

DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW (1981)

When a mentally ill man is lynched for a crime he didn’t commit, the country boys responsible seek to cover their tracks, but a mysterious scarecrow undertakes to kill them all. Not as gory as you’d expect, though there are some imaginative farm-tool related deaths, while at times it’s also rather sad. Veteran horror writer, Frank de Felitta, directed it for TV, which may explain its lack of fame in modern times.

SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES (1983)

In rural Illinois, two kids are captivated by the arrival in town of Mr Dark’s mysterious and grotesque carnival, gradually deducing that these aren’t normal entertainers, they’re actually the much-feared ‘Autumn People’. Ray Bradbury’s revered slice of fantastical Americana doesn’t translate ideally to the big screen – he and direct Jack Clayton fell out a lot – but you can rarely go wrong with Mr. Bradbury.

ANGEL HEART (1987)

A war-scarred PI pursues a missing singer around Harlem, a trail that finally leads down south into a world of hellish hoodoo. William Hjortsberg’s Gothic noir gets the Alan Parker treatment, Parker purposely taking it out of New York and into the Bayou, the resulting film so risque in parts that it got into a big wrangle with the censors. De Niro and Rourke add serious quality.

PUMPKINHEAD (1988)

When dirt-bikers run down a small child, the bereaved father begs a woodland witch for vengeance, and a horrific creature is raised from the pumpkin patch. Special effects whizz Stan Winston finally got into the director’s chair for this low budget but hugely effective adaptation of Ed Justin’s poem. Lance Henrikson brings complexity, the monster brings genuine terror.

THE MEDIUM (2021)

A Thai film crew heads way inland to interview Nim, a village matriach who claims to have been possessed by the spirit of Ba Yan, a goddess of the old religion. Director Banjong Pisanthanakun creates an atmosphere of visceral dread in this fast-moving found footage study of the old meeting the new, and all set against a tropical backdrop rich in folklore and superstition.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

MOLOCH (2022)

A Dutch woman, traumatised as a child by a violent attack on her family, now lives a secluded life on the edge of marshland in the middle of nowhere. However, as an archaeological team start uncovering bog bodies, clues suggests than an ancient cult is still active. A tad slow, but esoterica mingles with bleakness in a typical Euro-horror outing. Nico van den Brink directs his own script with a sure hand.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

by Michael McDowell (1979)

Outline

Pine Cone, Alabama, the mid-1960s.

It’s the heartland of the rural South, but the Vietnam War has reached its tentacles even into this sleepy backwater. Local boy, Dean Howell, gets his call-up papers, but before he can ship out to Nam, he suffers a critical injury on the range, when a rifle, made in the munitions factory at Pine Cone no less, blows up in his face. A blinded, zombified mute, he is honourably discharged and sent home to become the problem of his hardworking but very tired wife, Sarah, and his middle-aged mother Jo, who is not just lazy, obese and relentlessly vicious-tongued, but who harbours grudges against almost everyone she knows, usually for the most imaginary of slights.

Sarah’s constant exhaustion is due partly to her astonishing workload at the factory, where she functions on one of the actual conveyor belts along which travel the same rifles that injured her husband, but mainly because when she gets home she becomes Jo’s personal skivvy as well as the main carer for Dean. Becca Blair, her slightly older friend and neighbour, constantly harries her to stand up for herself, to make Jo share in the chores, but Sarah is a passive sort, who gets through either by trying to persuade herself that this is her lot in life, or alternatively, by grabbing a couple of moments’ rest here and there and simply not thinking about it.

Then, something shocking happens.

Larry, one of the supervisors at the munitions plant, and an old friend of Dean’s, comes to visit, and is genuinely and visibly shaken to see the paralysed, bandage-wrapped condition of the young ex-soldier. Even then, Jo Howell doesn’t have much time for Larry, but rather to Sarah’s surprise, she gives him a present for his wife, an exotic looking medallion, or amulet, hanging from a gold chain. No real explanation is offered and Larry doesn’t quite know what to make of it, but to avoid being rude, he takes the gift home and presents it to his wife, Rachel.

Later that evening, having tried the amulet on and found that it suits her, Rachel poisons Larry and then sets the house on fire while her children are in bed. All of them die in the subsequent inferno, Rachel included.

The whole town is appalled by what seems to have been an atrocious accident, with the exception of Jo Howell, who, from what Sarah can see, is smugly satisfied.

Jo, it seems, continues to blame everyone in the town for her unhappy life, and the state of her son. She particularly blamed Larry for the latter because she believed he was in a position to make Dean an essential worker and therefore remove him from any danger of being drafted. Sarah is hardly surprised by such mean-spiritedness. In truth, she reviles Jo, only staying with her out of her sense of duty as a wife and daughter-in-law. But worse horrors are now to be visited on Pine Cone.

Within a day or so, a cop assessing the ruins of the burned-down house comes into possession of the amulet, passing it on to his own wife. That same night, she too turns homicidal, puncturing his brain by stabbing him through the ear with an ice pick, before falling on broken glass and dying herself from a severed jugular.

A terrifying, self-repeating pattern appears to have been set in motion, the amulet finding its way from one new owner to the next, every new owner then committing brutal murders before dying, him or herself, through some incredibly unlikely accident, each one seemingly more gruesome than the last.

Increasingly certain that it’s something to do with the amulet, Sarah confronts Jo, only to be told that it came from a catalogue and doesn’t have any kind of power. In fact, the idea seems so ridiculous, even to Sarah, that she hesitates to mention it to Becca, though the ongoing succession of horrific deaths – a farmer whose skull is crushed by a tree branch wielded like a club, a farmer’s wife hurled off a bridge into a rushing river, another farmer’s wife trampled and savaged by a formerly placid but now insanely out-of-control mother-pig – gradually persuades her.

Even Becca, who is superstitious to her bones, struggles to buy into the theory that the amulet is causing these acts of murderous rage, until the two of them hold a séance together and are delivered some frightening if non-specific messages.

But who will believe them?

The amulet, meanwhile, continues to make its round of Pine Cone’s citizens, usually in secret as everyone seems to get hold of it in some kind of underhand fashion, in which case the first the rest of the community hears about it is when the owner’s loved ones have been slain, they themselves following shortly afterwards.

At this rate, Sarah thinks, unless she can do something soon, the whole town is likely to perish …

Review

Michael McDowell was a sadly short-lived American horror author, though in the time he was active, from 1979, when he had his first novel published, this one in fact, The Amulet, until his premature death in 1999 at the age of 49, he was very prolific.

Whatever his long-term plans were, this debut novel of his, reissued in 2013 in a very neat new package by Valancourt Books, originally came about in unusual if macabre circumstances, when McDowell and a friend got together and to amuse themselves, tried to pass the time creating as many gory deaths as they could think of derived from everyday appliances. The two of them clearly had ghoulish and vivid imaginations, because they came up with a heck of a lot. On top of those previously mentioned, you can also add decapitation by ceiling fan, mangling by hay-baler and the almost unbearably horrible laundering of a young baby in a washing machine, with many others to follow.

I’m not sure at which point McDowell decided there was a novel in this (or even a screenplay, as that is the form in which The Amulet was first written), but despite the incredibly lurid sounding material that he’d given himself to work with, once he’d actually started writing, he quickly pushed it beyond the norms of routine horror, the story taking us deep into the heart of his native southland, evoking a distinct air of the Southern Gothic.

Many aspects of life in that world are touched upon convincingly. It’s the mid-1960s and the Civil Rights Movement is in progress, but Alabama is resisting, and folks down there still lead segregated lives. The whites themselves are not vastly happier than their black ‘across the river’ neighbours, having hot summers and barren winters to deal with, living in poor-quality housing and engaged in mind-numbing but physically demanding work. The pleasures these people enjoy, of both races, are few and far between: the occasional bit of hunting or fishing, but mostly, and quite briefly, sitting on rockers on their creaky old porches, grumbling about so-called friends and neighbours, while knowing nothing about the rest of the world and caring even less.

It’s all very atmospheric, and a cut above most horror-writing of that era. All that said, whether the book can really be classified as a great horror novel, I’m not so sure. Valancourt have certainly done the reading world a favour in bringing it back to the light, for it has huge merits, but the mysterious amulet is never really explained (unless you assume that it’s some hoodoo-type transmitter for Jo Howell’s inherent vindictiveness, though that is never stated), while the narrative overall is a bit predictable and in the end becomes quite repetitive.

I don’t often say this about classily written books – because The Amulet is expertly and even beautifully written, often avoiding outright gratuitousness (apart from in the finale, which is a Carrie-esque explosion of grisliness) – but even though it’s less than 300 pages long, I felt a vague sense of relief as the end approached, simply because, well-staged and imaginatively gory though they are, I didn’t think I could sit through yet another elaborate death scene.

It holds together well enough. The dialogue crackles with believability (McDowell had a real ear for his own people), while the characters are vivid, the villains in particular – as evil and horrific hags go, Jo Howell will take some beating – while the sense of time and place, as I say, is immaculate. But all this really does, if I’m bluntly honest, is ensure that the procession of grotesque murders is all nicely packaged.

It’s a book worth reading, though. It will keep you entertained, and it’s a great glimpse into the early career of a very fine author, who would go on to do much better things later, but was taken from us all too soon.

And now, my usual high-risk addendum of who should play what if this property ever hits the screen. Only a bit of fun, of course, though you never know: Michael McDowell first wrote The Amulet as a drama after all. Here would be my current choices (price-tag no object, of course):

Sarah Howell – Erin Moriarty

Jo Howell – Conchata Ferrell

Becca Blair – Elizabeth Olsen

Sheriff Garret – Steve Buscemi

Outline

Pine Cone, Alabama, the mid-1960s.

It’s the heartland of the rural South, but the Vietnam War has reached its tentacles even into this sleepy backwater. Local boy, Dean Howell, gets his call-up papers, but before he can ship out to Nam, he suffers a critical injury on the range, when a rifle, made in the munitions factory at Pine Cone no less, blows up in his face. A blinded, zombified mute, he is honourably discharged and sent home to become the problem of his hardworking but very tired wife, Sarah, and his middle-aged mother Jo, who is not just lazy, obese and relentlessly vicious-tongued, but who harbours grudges against almost everyone she knows, usually for the most imaginary of slights.

Sarah’s constant exhaustion is due partly to her astonishing workload at the factory, where she functions on one of the actual conveyor belts along which travel the same rifles that injured her husband, but mainly because when she gets home she becomes Jo’s personal skivvy as well as the main carer for Dean. Becca Blair, her slightly older friend and neighbour, constantly harries her to stand up for herself, to make Jo share in the chores, but Sarah is a passive sort, who gets through either by trying to persuade herself that this is her lot in life, or alternatively, by grabbing a couple of moments’ rest here and there and simply not thinking about it.

Then, something shocking happens.

Larry, one of the supervisors at the munitions plant, and an old friend of Dean’s, comes to visit, and is genuinely and visibly shaken to see the paralysed, bandage-wrapped condition of the young ex-soldier. Even then, Jo Howell doesn’t have much time for Larry, but rather to Sarah’s surprise, she gives him a present for his wife, an exotic looking medallion, or amulet, hanging from a gold chain. No real explanation is offered and Larry doesn’t quite know what to make of it, but to avoid being rude, he takes the gift home and presents it to his wife, Rachel.

Later that evening, having tried the amulet on and found that it suits her, Rachel poisons Larry and then sets the house on fire while her children are in bed. All of them die in the subsequent inferno, Rachel included.

The whole town is appalled by what seems to have been an atrocious accident, with the exception of Jo Howell, who, from what Sarah can see, is smugly satisfied.

Jo, it seems, continues to blame everyone in the town for her unhappy life, and the state of her son. She particularly blamed Larry for the latter because she believed he was in a position to make Dean an essential worker and therefore remove him from any danger of being drafted. Sarah is hardly surprised by such mean-spiritedness. In truth, she reviles Jo, only staying with her out of her sense of duty as a wife and daughter-in-law. But worse horrors are now to be visited on Pine Cone.

Within a day or so, a cop assessing the ruins of the burned-down house comes into possession of the amulet, passing it on to his own wife. That same night, she too turns homicidal, puncturing his brain by stabbing him through the ear with an ice pick, before falling on broken glass and dying herself from a severed jugular.

A terrifying, self-repeating pattern appears to have been set in motion, the amulet finding its way from one new owner to the next, every new owner then committing brutal murders before dying, him or herself, through some incredibly unlikely accident, each one seemingly more gruesome than the last.

Increasingly certain that it’s something to do with the amulet, Sarah confronts Jo, only to be told that it came from a catalogue and doesn’t have any kind of power. In fact, the idea seems so ridiculous, even to Sarah, that she hesitates to mention it to Becca, though the ongoing succession of horrific deaths – a farmer whose skull is crushed by a tree branch wielded like a club, a farmer’s wife hurled off a bridge into a rushing river, another farmer’s wife trampled and savaged by a formerly placid but now insanely out-of-control mother-pig – gradually persuades her.

Even Becca, who is superstitious to her bones, struggles to buy into the theory that the amulet is causing these acts of murderous rage, until the two of them hold a séance together and are delivered some frightening if non-specific messages.

But who will believe them?

The amulet, meanwhile, continues to make its round of Pine Cone’s citizens, usually in secret as everyone seems to get hold of it in some kind of underhand fashion, in which case the first the rest of the community hears about it is when the owner’s loved ones have been slain, they themselves following shortly afterwards.

At this rate, Sarah thinks, unless she can do something soon, the whole town is likely to perish …

Review

Michael McDowell was a sadly short-lived American horror author, though in the time he was active, from 1979, when he had his first novel published, this one in fact, The Amulet, until his premature death in 1999 at the age of 49, he was very prolific.

Whatever his long-term plans were, this debut novel of his, reissued in 2013 in a very neat new package by Valancourt Books, originally came about in unusual if macabre circumstances, when McDowell and a friend got together and to amuse themselves, tried to pass the time creating as many gory deaths as they could think of derived from everyday appliances. The two of them clearly had ghoulish and vivid imaginations, because they came up with a heck of a lot. On top of those previously mentioned, you can also add decapitation by ceiling fan, mangling by hay-baler and the almost unbearably horrible laundering of a young baby in a washing machine, with many others to follow.

I’m not sure at which point McDowell decided there was a novel in this (or even a screenplay, as that is the form in which The Amulet was first written), but despite the incredibly lurid sounding material that he’d given himself to work with, once he’d actually started writing, he quickly pushed it beyond the norms of routine horror, the story taking us deep into the heart of his native southland, evoking a distinct air of the Southern Gothic.

Many aspects of life in that world are touched upon convincingly. It’s the mid-1960s and the Civil Rights Movement is in progress, but Alabama is resisting, and folks down there still lead segregated lives. The whites themselves are not vastly happier than their black ‘across the river’ neighbours, having hot summers and barren winters to deal with, living in poor-quality housing and engaged in mind-numbing but physically demanding work. The pleasures these people enjoy, of both races, are few and far between: the occasional bit of hunting or fishing, but mostly, and quite briefly, sitting on rockers on their creaky old porches, grumbling about so-called friends and neighbours, while knowing nothing about the rest of the world and caring even less.

It’s all very atmospheric, and a cut above most horror-writing of that era. All that said, whether the book can really be classified as a great horror novel, I’m not so sure. Valancourt have certainly done the reading world a favour in bringing it back to the light, for it has huge merits, but the mysterious amulet is never really explained (unless you assume that it’s some hoodoo-type transmitter for Jo Howell’s inherent vindictiveness, though that is never stated), while the narrative overall is a bit predictable and in the end becomes quite repetitive.

I don’t often say this about classily written books – because The Amulet is expertly and even beautifully written, often avoiding outright gratuitousness (apart from in the finale, which is a Carrie-esque explosion of grisliness) – but even though it’s less than 300 pages long, I felt a vague sense of relief as the end approached, simply because, well-staged and imaginatively gory though they are, I didn’t think I could sit through yet another elaborate death scene.

It holds together well enough. The dialogue crackles with believability (McDowell had a real ear for his own people), while the characters are vivid, the villains in particular – as evil and horrific hags go, Jo Howell will take some beating – while the sense of time and place, as I say, is immaculate. But all this really does, if I’m bluntly honest, is ensure that the procession of grotesque murders is all nicely packaged.

It’s a book worth reading, though. It will keep you entertained, and it’s a great glimpse into the early career of a very fine author, who would go on to do much better things later, but was taken from us all too soon.

And now, my usual high-risk addendum of who should play what if this property ever hits the screen. Only a bit of fun, of course, though you never know: Michael McDowell first wrote The Amulet as a drama after all. Here would be my current choices (price-tag no object, of course):

Sarah Howell – Erin Moriarty

Jo Howell – Conchata Ferrell

Becca Blair – Elizabeth Olsen

Sheriff Garret – Steve Buscemi

No comments:

Post a Comment