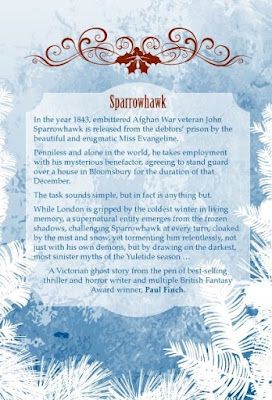

Okay, well it’s still a few weeks off Christmas, but the year is definitely waning, and for this reason I want to talk a little bit today about SPARROWHAWK, a festive novella of mine: a ghost story, needless to say, set in the depths of snowy Victorian Britain. It was first published back in 2010, but as you can see from the image on your right, it’s now out again, both in paperback and ebook, having been given a complete makeover. On top of all that, there’s an Audible version as well, coming out very soon.

Okay, well it’s still a few weeks off Christmas, but the year is definitely waning, and for this reason I want to talk a little bit today about SPARROWHAWK, a festive novella of mine: a ghost story, needless to say, set in the depths of snowy Victorian Britain. It was first published back in 2010, but as you can see from the image on your right, it’s now out again, both in paperback and ebook, having been given a complete makeover. On top of all that, there’s an Audible version as well, coming out very soon.

In addition today, because we’re talking a period piece with strong horror elements, I thought this might also be the appropriate time for me to review and discuss Kate Ellis’s ultra-spooky WW1 era serial killer thriller, A HIGH MORTALITY OF DOVES.

If you’re only here for the Kate Ellis review, that’s fine as always. And, as usual, you’ll find it in the Thrillers, Chillers section at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Speed right down there now, if that’s your choice.

But first, as promised above, it’s time for my own personal …

Winter soldier

You may recall that towards the end of the 2000s, we had a succession of very cold and snowy winters here in the UK. At the time, these inspired me to fully develop a novella idea I’d been playing about with for some time, though the actual core of the story was influenced – very mysteriously, I now feel – by an inexplicable dream I had concerning a Victorian soldier called John Sparrowhawk (yes, the name was given to me too!), who returns home from war traumatised and alone, only to find himself embroiled in a chilling Christmas mystery.

I finally started sketching things out in November 2009, during which month it was already snowing here in Lancashire and what increasingly looked as if it was going to be a very traditional Christmas was almost upon us. From there on, everything seemed to fall into place, the whole storyline spinning itself out in front of me, the characters dropping into the plot one by one of their own volition.

I’d always felt that, while writing a Victorian-era Christmas ghost story would be following a well-worn path – there are so many prototypes, after all – what might be a little different would be trying to create one that spoke genuinely of its period and of the festive season and, at the same time, had a relevance for today. And somehow, I felt in myself – and okay, I know I’m the author so obviously I was biased – that SPARROWHAWK might just do that.

Inevitably, as it was scheduled to run to 40,000 words, it wasn’t finished in time for that Christmas. In fact, I was still writing it at Easter 2010, which fell during a gloriously warm and sunny April (and that increased the challenge dramatically, trust me) but the novella was ready by the following autumn, and picked up by independent publisher, Pendragon Press, who, adorning it with a splendidly spectral cover by artist, James Higgins, published it the following December, which, again as fortune would have it, was very cold and very snowy.

The book seemed to do well. The paperback edition sold out quickly, while the ebook version just went on and on. In 2011, it was shortlisted for the British Fantasy Award in the capacity of Best Novella, but lost out to Simon Clark’s excellent HUMPTY’S BONES (if you’re going to lose out, you might as well lose out to something that’s really good, I always say). Only a year after that did its shelf life begin to wind down.

So why, you may wonder, a decade later, am I bringing out this completely new paperback edition of SPARROWHAWK complete with a snazzy new cover courtesy of the inexhaustible Neil Williams, and not only that, putting out an original Audible version too (as narrated by Greg Patmore, who did such an amazing job with my autumnal horror / thriller of 2019, SEASON OF MIST)?

Well, it’s simple. On a personal front, I may be better known these days as a writer of crime thrillers than ghost and horror stories, but I like to think that I still have a foot in both camps and I want my new readers to know about this and to read SPARROWHAWK. But at the same time, we can’t pretend that period supernatural thrillers are not back in a big way. In these final years of the 2010s, authors like Laura Purcell, Michelle Paver and Diane Setterfield have forged a dynamic new path for the period chiller subgenre, weaving in gothic and darkly romantic elements alongside vivid historical detail and of course that invaluable 21st century social relevance, to create an entirely new experience for ghost story fans.

Does SPARROWHAWK hit these same buttons?

I’d like to think so, but as I’ve already said, I’m biased. It’s up to you guys, really.

The Kindle edition is still available now as it always was, but the new-look paperback version is out as of yesterday, the Audible due in the next couple of weeks.

And now, just in case you need your appetites whetting even more, here’s a handful of brief trailers:

He approached it, frightened but at the same time fascinated.

The elf made no move, and when he got close, he saw why. It wasn’t a real man, but a marionette. It was life-size, but its face and hands were carved from jointed wood and had been crudely painted. Its body and limbs were suspended by strings, which rose towards the ceiling but there were lost in dimness. It was also – and this was perhaps the most disquieting thing of all – a close representation of his father.

It seemed that Doctor Joseph Sparrowhawk, the one-time academic, philosopher, publisher and pamphleteer, was now little more than a comic mannequin. Its head lay to one side, its eyes glass baubles containing beads designed to roll crazily around. Its chin and nose were exaggerated, Punch-like, in the tradition of the season, but the lank white hair was the same, the white side-whiskers were the same, the prominent brow, the small, firm mouth …

Despite the intense cold, the mob was in full strength and voice, all classes and creeds represented, the coster folk eagerly supplying them with wintry consumables, everything from boiled puddings to roast chestnuts and hot coffee. Excitable urchins darted back and forth; occasionally a beadle or constable managed to get hold of one and whipped him until he yowled, before kicking him on his way. A tall placard revealed the presence of a long-song seller. “Three yards a yenep, three a yenep!” he shouted hoarsely, as he told the ghoulish tale of James Keggs, a buckle-maker from Southwark, who had lured four unfortunate women back to his cellar room, and there throttled them and raped their corpses. Several well-to-do ladies did the honourable thing by fainting in their carriages.

“Four victims,” Miss Evangeline said. “That’s two short of your tally.”

“Hardly,” Sparrowhawk replied. “My full tally would make your toes curl.”

With another low growl, this one mewling and prolonged, the lion-thing tore off its dress shirt. The naked torso beneath was massive of shoulder and chest, padded all over with muscle, rich with thick, tawny fur. The monster hunched low, the entire room reverberating to its growls. Fleetingly Sparrowhawk saw its eyes again: pits of molten gold. With an ear-splitting roar, it charged, still on two legs but in a stooped, gambolling run, swerving in and out of the moonlight.

Sparrowhawk knew that it would leap on him and tear him apart, snap his limbs, flay the flesh from his ribs, clamp his skull with its colossal jaws, its ivory teeth sinking like bayonets through skin and bone ...

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

by Kate Ellis (2017)

Outline

It’s 1919, and Britain is still reeling from the horrors of the trenches. But the village of Wenfield in Derbyshire appears to have suffered more than most. Numerous of its young men failed to return, while others have only done so after being horribly wounded or shellshocked, many of their families broken as a result. As if this isn’t difficult enough for the grief-stricken local population, a bizarre series of crimes now commences.

It begins with Myrtle Bligh, a young woman who volunteered at the wartime hospital set up in the nearby stately home, Tarnhey Court. Though she believes her fiancé, Stanley, killed on the Somme, she is stunned to suddenly receive a letter from him explaining that he is alive but in trouble, and that he needs to have a secret meeting with her out in nearby Pooley Woods. Excited beyond belief, Myrtle rushes out there, but when Stanley confronts her in the shadow of the trees, he is nothing like the man she remembers. He is nothing like any man at all.

A short time later, Myrtle is found murdered, ripped apart by a military bayonet, her mouth slit to the ears, with a dead dove shoved inside it.

The investigation is initially undertaken by the local constabulary, led by the stolid but unimaginative Sergeant Teague, while the medical examination is spearheaded by local GP, the cold and rather reserved Dr Winsmore. Fascinated by this ghoulish turn of events is Winsmore’s daughter, Flora, who served alongside the deceased Myrtle as a nurse at Tarnhey Court, and thanks to this experience, is disturbed neither by gruesome injuries nor the fast-spreading rumour that a ghostly soldier with a nightmarish face has been seen lurking on the outskirts of the village.

Flora’s father disapproves of his daughter’s involvement. In fact, even though she helps out at his surgery, he even tries to dissuade her from applying to nursing college so that she can take up the profession full-time, seemingly determined to maintain her sheltered existence in the village and keep her under his benign but firm control.

However, this becomes increasingly difficult for him when there is another identical murder, Annie Dryden, whose son went missing in action years ago, summoned to meet him by anonymous letter, her butchered body subsequently found off an overgrown country lane.

Flora – despite being affected by her own personal loss, her brother having died in Flanders (or maybe because of this!) – determines to be useful and continues to attempt to inject herself into the investigation, though nothing about the case is simple. Wenfield is not just a village of gossip and backbiting, it’s also a village of secrets. Most people here resent someone or other among their neighbours, and almost everyone has something to hide. Even Flora’s own father has a murky past; his wife (Flora’s mother) supposedly ran off with a ‘fancy man’ some time ago, leaving him to enter into an unspecified relationship with his beautiful housekeeper, Edith, who became like a second mother to the young Flora until she left the family’s service during the war. Even the local landowner, Sir William Cartwright, and his son, Roderick – an old friend of Flora’s – have secrets, and not of the edifying kind. It isn’t even as if there aren’t other potential culprits. For example, Winsmore’s colleague, Dr Bone, is a handsome but superficially charming man, though Flora happens to know from personal experience that has an unhealthy appetite for young girls.

As such, it all seems too simple to Flora when the murder spree is blamed on a local simpleton, Jack Blemthwaite (mainly because he is the one who discovered Myrtle’s body). Inevitably, the charges don’t stick, but even then it takes a third murder, while Jack is in prison, for the case against him to be dropped.

Flora is mightily relieved when an experienced murder detective, Inspector Albert Lincoln, is at last sent up from Scotland Yard. Though battle-scarred himself and, thanks to great unhappiness at home, something of an introverted character, Lincoln is a clear-headed, analytical investigator, who immediately brings in a more professional approach, an aspect of his character that Flora finds instantly attractive.

She is also fascinated by his observations that, though all the female victims here were brutally murdered, there was never a sexual assault, suggesting that this isn’t just a rampaging lust killer. The so-called phantom soldier roaming the village outskirts is also significant, he feels, as is the symbolic insertion of a white dove – normally a sign of peace – into each of the corpses.

Gradually, under Lincoln’s (ever closer) guidance, Flora comes to realise that the killings in Wenfield, which are not necessarily over yet, are part of a complex web of malice and deceit, and that there are actually a great number of very viable suspects …

Review

When I first commenced reading A High Mortality of Doves, I wasn’t sure what to expect. The promotional material was intriguing, describing a series of murders occurring in a small rural community immediately following World War One, the chief suspect a phantom soldier with a painted, doll-like face. It promised all kinds of interest, hinting at everything from the historical novel to the village green murder mystery, from a spine-chilling MR James-type ghost story to the suspense-laden tale of a serial predator.

And indeed, in due course, the book ticks all of these boxes.

The immediate thing that struck me is how well Kate Ellis goes about recreating the immediate post-war atmosphere of small-town England in 1919, by which point, of course, the country hasn’t had anything like enough time to recover. Disproportionate numbers of young men never came home from the Front, while the ones who did carry hideous scars, either physically or mentally, or both.

This part of the book is particularly vividly done (without being heavy-handed), bringing it home to the reader with a bump just what it would have meant to live in a community like this, where the numbers of menfolk have been so cruelly depleted, where so many of the womenfolk, young and old alike, are bereaved. Inevitably, Wenfield is not a happy place, though concerted efforts are made by all to be ‘stiff upper lip’ about it, put on a brave face and get on with their lives (though already there are hints of the terrible Spanish Flu scourge that followed so quickly after World War One and also killed millions).

That’s the backdrop to the narrative, which is unique enough, though the story itself is more than a little bit compelling.

With Wenfield in mourning, and hardly a prosperous village anyway (this is industrial Derbyshire, not the leafy Home Counties), the mood is already very different from anything you’d find in the more typical cosy murder mystery, and yet now we have a brutal slayer and mutilator on the loose rather than a straightforward murderer, and if that isn’t horrific enough, evidence that he may or may not be supernatural in origin. It’s no spoiler to reveal that early on in the text, we see the killer for ourselves as he approaches his victims in lonely places, and he is indeed frightening, a ghastly apparition – ‘human yet not human,’ as the author describes him – someone you’d run a mile from even if he wasn’t about to carve you up with his bayonet. That doesn’t mean that A High Mortality of Doves is a horror story, but it certainly adds more than a frisson of fear to proceedings, particularly whenever another poor woman receives an anonymous message to go and meet a relative she’d thought lost in the mud and blood of the trenches.

Ultimately, of course, despite all these extra trappings, A High Mortality of Doves is still a whodunnit, Kate Ellis cleverly sprinkling her plot with a host of potential suspects … like Sydney Pepper and David Eames, who came back from war disfigured and possibly demented, or Roderick Cartwright, who signed up willingly but was kept out of harm’s way and now resents the hostility of the town’s widows, or like Dr Winsmore, who still can’t (or won’t) account for his wife’s absence, or, more than anyone else, like Dr Bone, who already has a history of sexual predation against women and girls (even though no one knows about this, or at least they don’t dare repeat the rumour because after all, it’s still the Age of Men).

In classic Midsomer Murders fashion, all of these individuals, and others like them, become feasible suspects, the focus of the investigation shifting back and forth between them as the plot twists and loops, the tide of suspicion turning constantly, Kate Ellis keeping the reader guessing right to its final pages, maintaining the satisfaction level throughout (though by the end, it feels like a very different story from the one you started, and I mean that in in a good way).

Another of the book’s strengths is its characters. Flora Winsmore makes for a spirited and likeable lead, and is nicely illustrative of the young women of that era, when World War One changed society and enabled the rise of the suffragette movement. The preceding years have allowed Flora to prove that she is as good and conscientious a worker as any of her male colleagues, having enjoyed the useful independence she found while nursing the wounded, and now keen to take it on full-time. The deep frustration she feels about her father’s refusal to accept this is understandable, and if she at times seems a little eager to thrust herself into the investigation, it’s forgivable given her proactive nature and the relationship she embarks on with Albert Lincoln.

Lincoln himself is an equally complex character, though he owes a little more to that golden age of fictional but sharp-eyed detectives who are invariably imported from outside the murder-stricken community to resolve a case quickly and with minimum fuss while all the locals remain flummoxed. Okay, it isn’t quite that simple, but Lincoln is a familiar figure to us, despite his various scars, though that doesn’t make him any the less reassuring a presence at the heart of this dark tale.

I will admit to having some doubts about the burgeoning romance between Lincoln and Flora, and couldn’t help wondering if it felt a little bit forced. Both characters at least appear to have solid moral centres, and while Flora’s desire to make a new life for herself in the modern world naturally leads her into the arms of a city man with real-life experience, Lincoln’s response appears to be rather callous considering that he’s already married and, though it’s a loveless match, the deep depression that his wife is entrapped in. Lincoln is a sad, rather noble figure, and his dalliance with the feisty Flora feels like a bit of a misstep to me, but that’s only one viewpoint, and lots of others have disagreed.

A High Mortality of Doves remains an engaging and atmospheric mystery, set against the authentically turbulent background of a nation in mourning and in flux. Scary and intriguing in equal parts, while the final devastating denouement is worth the price alone.

And now, the moment you’ve been waiting for. My attempt to cast A High Mortality of Doves. Don’t worry, I’ve not been given that actual task. Should we ever be fortunate enough to see this novel be adapted for film or TV, someone who knows what they’re doing will get the gig. This is just a bit of fun (as you’ll realise when you see how much money I’ve spent on the actors).

Flora Winsmore – Lucy Boynton

DI Albert Lincoln – Dominic Cooper

Roderick Cartwright – Aneurin Barnard

Dr Winsmore – Ian Hart

Dr Bone – Rory Kinnear

Sir William Cartwright – Guy Pearce

Edith Barton – Alison Pargeter

Sydney Pepper – Adrian Bower

David Eames – Jamie Bell

No comments:

Post a Comment