It may be perverse of me, but in a week when I’m proofing my

next thriller, have a glut of crime novels to read and a whole raft of new

horror movies to watch, I’m going to be talking about science fiction.

It may be perverse of me, but in a week when I’m proofing my

next thriller, have a glut of crime novels to read and a whole raft of new

horror movies to watch, I’m going to be talking about science fiction.

Yes, this is one of those ‘relaxing’ blogposts, which

is more designed to occupy readers during mid-morning tea breaks than impart crucial information to them.

To start with, I’m going to be reviewing and discussing – in

what I hope is my usual forensic detail – Alfred Bester’s sci-fi masterwork, THE STARS MY DESTINATION (as always, you’ll find that review towards the bottom end of today’s column).

On a not dissimilar subject, I’ll also be presenting a gallery of what I consider to be the 25 best ever science fiction book covers. It’ll be an entirely personal choice, of course; browsers and readers must feel free to disagree, or add suggestions of their own.

On a not dissimilar subject, I’ll also be presenting a gallery of what I consider to be the 25 best ever science fiction book covers. It’ll be an entirely personal choice, of course; browsers and readers must feel free to disagree, or add suggestions of their own.

Reaching for the stars

That’s not something I’ve ever done, basically.

Well, in purely metaphorical terms, I’ve tried to reach for

the stars … but when it comes to writing about journeys to the stars, in other

words penning sci-fi, that’s not something I’ve done a whole lot of.

Okay, I’ve done it a little. Students of my career (assuming

any such creature exists) will probably be familiar with my DR WHO output:

LEVIATHAN and HEXAGORA, two full-cast audio dramas, and SENTINELS OF THE NEW

DAWN, a Companion Chronicle, all courtesy of Big Finish Productions, which came

out in 2010 and 2011; SPOILSPORT, a short story of 2008; HUNTER’S MOON and TALES OF TRENZALORE, published by BBC Books in 2012 and 2014; and THRESHOLD, the pilot episode of the Dr Who spin-off series, COUNTERMEASURES

(Big Finish again) in 2012.

Okay, I’ve done it a little. Students of my career (assuming

any such creature exists) will probably be familiar with my DR WHO output:

LEVIATHAN and HEXAGORA, two full-cast audio dramas, and SENTINELS OF THE NEW

DAWN, a Companion Chronicle, all courtesy of Big Finish Productions, which came

out in 2010 and 2011; SPOILSPORT, a short story of 2008; HUNTER’S MOON and TALES OF TRENZALORE, published by BBC Books in 2012 and 2014; and THRESHOLD, the pilot episode of the Dr Who spin-off series, COUNTERMEASURES

(Big Finish again) in 2012.

Before any of that, way back in 1996, there was also A

GLITCH IN TIME, a short story I wrote for the non-Dr Who spoken-word (these days it

would be called ‘audible’) anthology, OUT OF THIS WORLD; this one has a really special place in my heart as, despite it existing in our universe rather than the Whoniverse, my particular contribution to this excellent anthology was narrated by the late, great Jon Pertwee.

But the majority of this lot, as I’ve already said, is Dr

Who-related, and therefore occupies a little world of its own, sitting slightly apart

from the sci-fi mainstream. However, that doesn’t mean that I’m not a big fan or eager reader of all those other wondrous tales.

But the majority of this lot, as I’ve already said, is Dr

Who-related, and therefore occupies a little world of its own, sitting slightly apart

from the sci-fi mainstream. However, that doesn’t mean that I’m not a big fan or eager reader of all those other wondrous tales. My father, Brian Finch (right), another late, great character, and an author in his own right, was a huge science fiction buff, and helped turn me onto it as a genre when I was very young.

Perhaps that is why I’m slightly biased to the older school, as

you’ll see when I present my 25 Best Covers. I hasten to add that I

read the modern stuff too. But to put a gallery together like this, you really

have to look for those cover-images that made the biggest impact on you, and in my case certainly, such a task took me back to my earliest days.

As with previous galleries –

I did horror and crime on Oct 22 and Sept 10 respectively – I’m sticking to

English language editions, as it would be too complex and time-consuming to go

beyond that. Anyway, without further ado, here are what I consider to be …

THE 25 BEST SCIENCE FICTION COVERS OF ALL TIME

1. THE CHRYSALIDS

John Wyndham (Penguin, 1970)

Not the first vision in sci-fi of a hellish post-apocalyptic world, but certainly one of the most intelligent, John Wyndham’s 1955 classic (originally published by Michael Joseph), takes us to a UK decades after the bombs have dropped, where a form of fundamentalist feudalism has reformed what remains of society, and as this marvellous cover amply illustrates, mutation is a source of open war.

2. MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM!

Harry Harrison (Orb, 2008)

Probably best remembered for the 1973 movie version, Soylent Green (which considerably changed the plot), Harry Harrison’s 1966 masterpiece (first published by Penguin) envisions a world where overpopulation has collapsed all infrastructure, leading to societal chaos, and follows the fortunes of several hapless individuals. This Orb cover is clean, simple, and almost tells the story on its own.

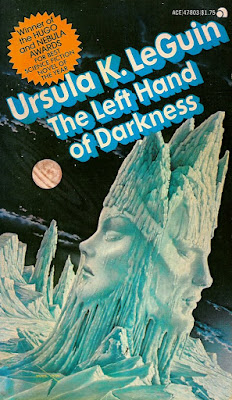

3. THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS

Ursula K. LeGuin (Ace Books, 1985)

The novel that made Ursula LeGuin’s name (and surely the best book title ever). First published in 1969 by Ace Books, the author’s career-long fascination with anthropology hits new heights of ‘what if'’, when, in a different universe to ours, a male ambassador makes contact with an ambisexual race, and fails to understand it - to a near fatal degree. Described as the first foray into ‘feminist sci-fi’

4. THE BLACK CORRIDOR

Michael Moorcock (Mayflower, 1973)

The embodiment of ‘new wave’ science fiction, as tough businessman, Ryan, takes a select band of friends on a stolen spaceship to escape an impending nuclear war. The trouble is that, while they lie in stasis, he must remain awake to steer the ship on its seven-year journey. First published by Ace in 1969, this later cover perfectly encapsulates his terrifying descent into solitude-induced madness.

5. DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP?

Philip K. Dick (Doubleday, 1968)

One of the most famous sci-fi novels of all time, though mainly because of the movie, Blade Runner, which differs in many ways, this deeply moving piece of visionary writing - and this is the original wonderful cover, as produced by Doubleday back in 1968! - sees a conscience-stricken bounty hunter pursuing a rogue band of human-like androids through a world dying from radiation poisoning.

6. THE RINGS OF SATURN

Isaac Asimov (New English Library, 1974)

The final installment in the Lucky Starr series, a collection of sci-fi novels written for younger readers (despite this scary later cover). First published by Doubleday in 1958, it tells an adventurous spy story set in the Saturnian system, but, Asimov being Asimov, is nevertheless filled with advanced scientific thinking, and was viewed by many as a thought-provoking commentary on the Cold War.

7. FAHRENHEIT 451

Ray Bradbury (Ballantine, 1953)

The ultimate Dystopia, as a young fireman becomes disillusioned with his job - which is not putting out fires, but starting them, using mountains of forbidden literature as fuel! What better cover could illustrate the anguish the author felt, not just about book-burning, but about book abolition in general? Written as a stinging response to McCarthyism, and viewed by many as Bradbury’s greatest work.

8. HELLSTROM’S HIVE

Frank Herbert (Gollancz, 2011)

For once, not the original Doubleday cover, as first published in 1973, but an infinitely superior later one. Inspired by the speculative sci-fi/horror documentary of 1972, The Hellstrom Chronicle, this exceptional and chilling novel tells the tale of an undercover agent and his discovery of a secret society modelled along the lines of social insect communities, and the devastating events that follow.

9. THE DROWNED WORLD

J.G. Ballard (Penguin, 1965)

Another post-apocalyptic saga, though this time it isn’t Man’s fault, solar flares having returned much of the Earth to a topical Triassic paradise, where even a hard-headed scientific research team find themselves regressing mentally into a dreamlike, tribal state. First published in 1962 by Berkley, this later, postmodern cover hints at the darker, grosser elements that lie beneath Eden’s genial facade.

10. STAR MAKER

Olaf Stapledon (Gollancz, 1999)

First published by Methuen in 1937 - pretty incredibly, given how long that was before space exploration became a real thing! - this remarkable odyssey of a sci-fi novel charts an Englishman’s journey through the universe in a disembodied state, at the same time telling us the story of all things and hitting us with a deluge of philosophy. How to illustrate such other than with a cover like this?

11. THE STARS MY DESTINATION

Alfred Bester (Gollancz, 2010)

In some ways, this 2010 cover to a novel written in 1956 (first published by Signet) almost softens the ferocious character of tiger-faced Gully Foyle, who ruthlessly pursues vengeance across a solar system wracked by interplanetary war, but it remains one of the most iconic in modern sci-fi, putting the man first and foremost above the futuristic setting, and perfectly capturing the author’s intention.

12. I, ROBOT

Isaac Asimov (Gnome Press, 1950)

The wonderfully basic cover to the original publication, which, though it only partly provided the story for the recent Hollywood epic (that movie also owes quite a bit to Eander Binder’s same-titled short story of 1939), saw Asimov break phenomenal ground with a collection of interlinked stories and essays concerning the development and gradual humanisation of an imaginary android species.

13. ONE WAY

S.J. Morden (Gollancz, 2018)

The most recent entry in the gallery, and in some ways more a ‘space-thriller’ than pure science fiction, but with a planetary geologist at the writing helm you know you’re in for an ultra-realistic assessment of just what it would mean for a party of condemned men sent to build a colony in the frozen wastes of Mars, who have no way back, and who, one by one, are then systematically murdered.

14. THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

H.G. Wells (New American Library, 1986)

An appropriately horrific cover for what in truth was a horror story. Everyone is familiar with Wells’s masterly 1897 tale (first pub. by William Heinemann) of a late-Victorian era Earth at the mercy of an amoral and super-powered alien species prepared to wreak a total holocaust, but the transformation of our conquered world into a blood-soaked parody of Mars (as per this cover!) still has chilling impact.

15. STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND

Robert Heinlein (Ace Books, 1987)

A human raised by Martians returns to Earth as a kind of pseudo-messiah, and promotes libertarian concepts like free love and communal living, as this provocative cover illustrates. First published by GP Putnam in 1961, it was ahead of its time, but not by much, and is often seen as a prelude to the counter-culture - the very last thing those who knew Robert Heinlein would have expected of him.

16. BRAVE NEW WORLD

Aldous Huxley (Chatto & Windus, 1932)

The original, unforgettable cover to what is probably the most famous sci-fi novel ever written, though it’s as much a philosophical text in its study of a future world where hard scientific theory rules, human beings are produced in test-tubes, and though society is harmonious and productive, this comes at the cost of a cruel caste-system, psychological manipulation and extreme social control.

17. SWARM

Guy Garcia (Morphic Books, 2017)

A sci-fi novel you genuinely believe could happen - and in the not-to-distant future. The horror-esque cover nicely imagines the central antagonist, Swarm, an expert hacker and cyber warrior, who comes into possession of illegal experimental software, the resulting transformative effect of which goads him into seeking to change society without considering the potential catastrophic consequences.

18. THE ROAD

Cormac McCarthy (Alfred A Knopf, 2006)

Surely the last word on the apocalypse, though the author maintains that he never considered it sci-fi, penning it as a simple study of a father and son, this chilling epic still tells the story of an odyssey through a North America ruined by some unspecified disaster, leaving no stone unturned in its quest for misery and pain, and yet remains a lyrical masterpiece. This bleak, spare image sells it perfectly.

19. GATEWAY

Frederik Pohl (Penguin, 2008)

A suitably mind-blowing cover for the multi award-winning novel that kicked off an entire series of award-winners. First published by St Martin’s in 1977, it’s another of these incredible ‘imagine if’ sagas, in this case the human response to the discovery of a derelict alien space station, where all kinds of abandoned craft, with pre-set coordinates, promise immediate voyages to distant stars.

20. A TIME OF CHANGES

Robert Silverberg (HarperCollins, 1975)

First published by Doubleday in 1971, this timeless tale of repression and revolution comes to us in the form of an intense autobiography as a young telepath seeks to overthrow a culture so down on individuality that the use of words like ‘I’ and ‘me’ are classified as a cultural crimes, and show his people exactly what it means to be human. As the ghoulish cover above illustrates, that won’t be easy.

21. THE PALACE OF ETERNITY

Bob Shaw (Pan, 1972)

Originally published by Ace in 1969, this legendary sci-fi thriller never really needed an iconic cover to sell itself, but it got one eventually, as illustrated above. Master of his craft, Bob Shaw spins the action-packed but thought-provoking tale of an exhausted war veteran seeking redemption and refuge on the tranquil Poets’ World, only for the war to catch up with him again in the shape of his one-time comrades.

22. DUNE

Frank Herbert (New English Library, 1968)

Everyone’s favourite space epic, and the cover that most genre fans remember best, mainly because it comes so close to encapsulating James Herbert’s colossal, multi-sequel-spinning 1965 saga (Chilton) of two noble houses fighting each other to the death across an interstellar empire. Yes, that’s correct; Herbert re-set the War of the Roses in Outer Space and created the best-selling sci-fi novel in history.

23. DAY MILLION

Frederik Pohl (Ballantine, 1970)

The original cover to a seminal collection of short stories, in which the author gives full vent to his imagination, taking his readers through the many realms of science fiction, but at the same time addressing serious issues like trans-sexuality, racism, medical and technological advance - both the benefits and drawbacks of such, etc. Still regarded as a masterly work by a true genius of the genre.

24. THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES

Ray Bradbury (Bantam Spectra, 2003)

First published by Doubleday in 1950, this episodic but poetic vision of Man’s attempted colonisation of Mars and his inevitable clashes with its indigenous inhabitants commenced life as a series of short stories originally published in the 1940s. But this latter-day cover is still the best, perfectly imagining the barren red world, along with its mythical canals, as envisaged throughout the early days of astonomy.

25. THE GREEN BRAIN

Frank Herbert (New English Library, 1973)

One of Herbert’s lesser-known works, but a classic of its time, originally published by Ace in 1966 (as Greenslaves), and dipping into the expanding eco-consciousness in its tale of a human race at war with Earth’s flora and fauna, and the retaliation from the insect world, as experienced by a scientific expedition to the Brazilian jungle. This later cover says all you need to know about the ensuing terror.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime,

thriller, horror and sci-fi novels) – both old and new – that I have recently

read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will

certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by

the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books

in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly

enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these

pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts

will not be your thing.

Outline

In the 25th century, humanity has developed the power to

jaunt, most individuals now able to transport themselves up to 1,000 miles

simply by the power of thought. However, life has not improved greatly. Earth

society is going through constant social and economic flux as a result, and

though the solar system is fully colonised, the Inner Planets (Earth, Mars, and

Venus) are in ongoing conflict with the Outer Satellites (the moons of Jupiter,

Saturn and Neptune).

One casualty of this is the deep space cargo vessel, Nomad,

which belongs to the influential Presteign corporation. Damaged by rocket fire,

Nomad is now a drifting, incommunicado wreck with only one survivor on board,

crewman Gulliver ‘Gully’ Foyle, an ignorant, uneducated man, who nevertheless

stays alive against all the odds. He even manages to signal for help to passing

sister-ship, Vorga, also a Presteign vessel, but is astonished when it

deliberately ignores him, abandoning him to a terrible fate.

Infuriated beyond reason, Foyle manages to steer the

floating scrapheap into the Asteroid Belt, where a little-known tribe called

the Scientific People, a cargo cult who have long cut their ties with Earth,

imprison him and tattoo his face with tiger stripes.

Still bent on revenge – and now looking the part as well –

Foyle steals a ship to escape, and makes it back to Earth, where, in a barbaric

state, he rapes a gentle, telepathic woman called Robin Wednesbury, and

launches a one-man terrorist attack on Vorga, which fails and puts him in the

grasp of the company’s all-powerful CEO, a man simply called ‘the Presteign’,

someone who suddenly wants to know all about this errant crewman. It seems that

Nomad was carrying a newly-discovered mineral, PyrE, which could change the

course of the war – but Nomad is now lost, and only Foyle knows its

coordinates.

Foyle is interrogated by a fearsome private security officer,

the radioactive Saul Dagenham, but even Dagenham cannot break him, so he is

condemned to life imprisonment in the hellish subterranean jail, Gouffre

Martel. Here he befriends another convict, the resourceful Jisbella ‘Jiz’

McQueen, who educates him, advises him that it isn’t Nomad he should seek to

destroy, but whoever gave the order to ignore him, and finally helps him

escape.

Through Jiz’s criminal contacts, Foyle manages to remove the

tiger-stripes from his face – though in times of anger they show again –

educates himself further and augments his body so that he becomes a lethal

fighting-machine. He then treacherously cuts Jiz loose and reappears as the

dapper dandy, Geoffrey Fourmyle, bullying the unwilling Robin into helping him

penetrate Presteign high society.

Everything is going to plan, but there are still problems.

Those Vorga officers he tracks down involuntarily self-destruct before they can

tell him anything, while his determination to ruin Presteign is hampered by his

growing affection for the CEO’s beautiful daughter, the blind but

infrared-sensitive Olivia. Meanwhile, Robin hates and fears him, Jiz is

plotting something, and Foyle is troubled by an apparition he sees increasingly

often: himself wrapped in flames. At the same time, the Outer Satellites are

planning a massive attack, which they hope will win the war for them in one

overwhelming blow.

If things have been difficult for Foyle so far, vastly more terrible days lie ahead …

Review

On first reading The Stars My Destination, it would be quite

simple to write it off as straightforward space opera. The incredible

adventures of Gully Foyle and the personal changes he undergoes as, through

endless stress and suffering, he transcends the status of brute underling,

becoming first a wealthy, scheming sophisticate, and finally a godlike

intellectual, is more than a little bit reminiscent of Alexander Dumas’ classic

adventure, The Count of Monte Cristo. But if, after some protracted pondering,

that remains your sole assessment of this visionary sci-fi novel, you need to

read it again.

Comparisons between The Stars My Destination and The Count

of Monte Cristo are not wrong, and there’s a specific reason for that, Alfred

Bester, by his own admission, seeking to snare his audience with what initially

seems like a simple, exciting plot-line over which he can lay some complex but

wondrous notions.

Though initially an editor and script-writer for comics, by

the mid-1950s Bester was regarded as one of the world’s leading science

fiction writers (he ‘invented’ it, according to Harry Harrison), and if you

need further proof of that, just consider when reading The Stars My Destination

that he penned this astonishing story when the vast bulk of the public drew

their knowledge of the genre from movies concerned with insects grown to giant

size through atom bomb testing and threats posed to Earth by bulb-headed men

who spoke in senatorial US voices. That any serious sci-fi prophesying was done

by authors writing in that era is quite remarkable, but plenty of them did, and

yet Alfred Bester was ahead of the game even by those standards.

The concepts he presents us with in The Stars My Destination

were mind-boggling in their day, and in many ways still are, and yet the book

is also threaded with mindfulness of what these developments for mankind would

actually mean.

For example, in the 25th century (or the 24th, depending on

which edition you are reading), Man’s reach might stretch across the solar

system, but it isn’t as though Pluto is suddenly in our back yard. The vast

distances remain, especially as jaunting between planets is impossible. And so,

Earth has lost cultural contact with its colonies. They have become advanced

societies in their own right, and barely understand Earthlings, let alone see them

as friends, and when war breaks out, there is no empathy between the two sides.

Earth and the inner planets aren’t even aware of the outer satellites’ military

strength, while the cargo cult that abducts Foyle early in the book is a

completely isolated tribe, whose whole world is now the wreckage of ours.

The jaunt itself (named after scientist Charles Fort

Jaunte), was an amazing concept to 1950s audiences. Long before Star Trek ever

thought of it, the inhabitants of The Stars My Destination jump from A to B via

teleportation. But again, Bester ponders the upheavals that stem from this: for

instance, valuable high-class women must be kept in jaunt-proof isolation to

‘protect their honour’, while convicts can only be held in jaunt-proof solitary

confinement (resulting in hellhole prisons like Gouffre Martel).

More familiar concerns among sci-fi writers of Bester’s era

are also on show. Chemically and mechanically enhanced human beings don’t

remain human for long. Telepaths are in such demand that they must conceal

their talents from almost everyone. The author was also worried about the rise

of ultra-powerful corporations, and how in the future they might become empires

in their own right. The Presteign, though maintaining an urbane exterior, is utterly

ruthless, and has the full cooperation of the government’s own intelligence

agency, as represented by Peter Yang-Yeovil.

And yet, despite all this fascination with psi-power and

speculative science, the main driving force in the book is that most basic of

all human instincts, a yearning for revenge.

It is perhaps a nihilistic concept that the route to

godliness may lie with Man’s desire to get even with other men … but you

certainly can’t argue with it in The Stars My Destination as it’s given to us

so full-bloodedly. It’s illustrated visually in the form of Foyle’s tiger mask,

which even after he’s had it superficially removed, blazes to life whenever

he’s angry (surely one of the most impressive devices of its sort that I’ve

ever encountered in fiction). This vengeful nature is the single thing that constantly

drives Foyle, and lies at the heart of his thrilling escapes: from the floating

wreckage of Nomad, from the clutches of the asteroid tribe, and even from the

jaunt-proof subterranean prison. It is this same motivation which, in due

course pushes him to better himself – mainly so that he can infiltrate high

society, though unknowingly of course, it also pitches him towards the realm of

perfection.

Foyle makes an intriguing anti-hero. Appalling in his

behavior at some points – the attack on Robin Wednesbury, for example (which

would need to be excised out if ever the book were to make it to film) – but

also later on, when he plays the likeable but untrustworthy Fourmyle. But from

the outset, he is never intended to be an ordinary person, much less a person

of noble character. If anything, he is a metaphor for mankind’s own evolution

(and the path that Alfred Bester clearly hoped we would at some point take).

I don’t want to say anything more about The Stars My

Destination for fear of giving too much away, except to add that it’s well

worth its classic status, and that if some of the concepts seem standard in

sci-fi these days, that’s only because forward-gazing writers like Alfred

Bester made them so.

Optioned for movie development many times, but never yet

made and in fact described more than once as ‘unfilmable’, The Stars My

Destination is nevertheless another of those novels I would dearly love to see

on celluloid – either the big screen or TV – and so once again, I’m going to

pitch in with my own thoughts on a possible cast. (One quick note; it’s

currently in the hands of director Jordan Vogt-Roberts, who gave us Kong: Skull

Island, so you never know – anything is possible). In the meantime, though,

here are my picks for the leads:

Gulliver Foyle – Paul Bettany

Robin Wednesbury – Tessa Thompson

The Presteign – Ben Kingsley

Olivia Presteign – Lea Seydoux

Jisbella ‘Jiz’ McQueen – Rhona Mitra

Saul Dagenham – Rufus Sewell

Captain Peter Yang-Yeovil – Mathieu Amalric

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete