Outline

A nightmare tale told in three parallel strands.

In the 1860s, Elsie Bainbridge, a burned, mute and seemingly deranged woman, lies in a secure ward in St Joseph’s, a lunatic asylum deep in the English countryside. Here, the attentive Dr Shepherd provides her with an empty diary and encourages her to jot down the terrible events that led to the destruction of The Bridge, the stately residence she once called home, and her resulting mental collapse. The doctor is certain that only by giving her own twisted account of these incredible events, can Elsie prove to the authorities that she is clinically insane, and thereby evade the gallows. Despite this, Elsie resists for as long as she can, unable to revisit the horrors that have recently ruined her life, but in due course, inevitably, she succumbs.

Thus begins the second strand in the tale, with Elsie Bainbridge, now half a year younger, but pregnant and recently widowed, arriving at The Bridge, her late husband’s neglected country estate, in company with her self-confident younger brother, Jolyon Livingstone, and the cousin of her late husband, Sarah Bainbridge (who is even more grief-stricken than Elsie, as she has now seen everything that once belonged to her family pass into the hands of an in-law).

The Bridge is a drear, decaying edifice in a remote and desolate location, to which all kinds of unedifying legends are attached. The staff, used to having things their own way, are openly hostile and uncooperative, while the local villagers, who live in a permanently impoverished state, dislike everyone at the local manor house and blame them for all their ills, the direct cause of which, they suspect, is witchcraft.

Already traumatised at having lost her husband, and worn out by her pregnancy, Elsie struggles to adapt to this terrible environment. But when Jolyon returns to London to run the family business, the situation worsens as she and the ultra-timid Sarah begin hearing strange sounds at night. They trace these to a locked attic, which no one seems willing or able to open, though when Elsie manages this, she finds that it contains a 17th century diary, and a so-called ‘silent companion’: a flat, lifesize figure made from painted wood, depicting a child that is alarmingly similar in appearance to Elsie, herself, when she was young.

From here on, the terrors mount. There are more and more eerie noises in the house, while the silent companions, inexplicably, begin to multiply, appearing all over the building, at the ends of corridors or looking down from internal balconies, always, it seems, watching. The increasingly distraught Elsie thinks she recognises some of the persons they represent, while others are complete strangers, yet all are chilling in the intensity of their stares … and could it be Elsie and Sarah’s imagination, or do these horrible figures actually move around the house on their own when no-one is looking?

The 17th century diary, meanwhile (the third strand in our story), tells its own tale of menace, following the declining fortunes of Anne Bainbridge, whose husband, Josiah, is a country gent of minor importance in the years leading up to the Civil War. His one chance to impress comes unexpectedly, when King Charles I opts to visit The Bridge, the ancestral Bainbridge seat. Anne prepares The Bridge thoroughly, as any good chatelaine should, planning to treat her royal guests to a magnificent masque, but she has a dark and guilty secret: her habitual use of rural magic, which as a Christian woman she is certain will bring retribution on her at some point. Anne has called on the dark arts several times in the past to gain advantage, on one occasion to impregnate herself when she’d supposedly turned barren, the result of which was Hetta, her curious young daughter, who has beautiful ‘pixie’ looks, but is mute and distant, makes friends with outcasts and oddballs (like the local gypsies), and seems to possess a detailed, self-taught knowledge of herbal lore.

This is the age of witch-hunting, of course, but though the local villagers harbour suspicions about Anne and her little goblin, Hetta, they won’t dare say anything. More problematic is the attitude of Josiah, a muscular Christian in his own right, who also hates and fears witches. If he has any concerns about his wife and daughter, he keeps them to himself until the time of the king’s visit draws near, at which point he decides that Hetta is an embarrassment and must stay out of the way.

Anne is heartbroken for her daughter, but also fearful that God’s punishment is now looming, especially when Hetta withdraws into herself, becoming surly, truculent, and surrounding herself with an eerie cadre of brand-new friends, the Silent Companions …

Review

When I consider the traditional English ghost story, it invariably makes me think isolated manors, cold, misty landscapes, a vengeful entity, and, quite often, some nervous, damaged individual, either male or female, lured far from civilisation to meet this nemesis – and all of it set in that ageless if generic Victorian/Edwardian time-loop.

All these criteria are staples of the classic spooky tale, and whether dated or not in the 21st century – and that’s very subjective! – they surely can’t help but infuse a majority of us with a deep sense of foreboding, picking at what appear to be our deepest fears.

If you include yourself in that majority, then The Silent Companions is a book for you. But be warned from the outset, this is a seriously frightening foray into the genre. When Laura Purcell embarked on this novel, there was no intent to produce a ‘Gothic romance’, a ‘period mystery’ or a ‘supernatural thriller’. The Silent Companions is out-and-out horror.

Yes, it might have the trappings of an archetypical ghost story, something you’d expect to read in a firelit drawing room some snowy Christmas Eve (as I did), but the ghastly evil at The Bridge comes at us and our isolated heroine, Elsie, with a malicious brutality reminiscent of the merciless spirit in Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black, the manifestations growing steadily more disturbing (even if the early ones are done ultra-subtly), until it becomes obvious that an appalling crescendo will soon be reached.

Moreover, any suggestion that the malignancy here is perpetrated by a human hand is jettisoned early on by the presence of those awful watching figures, the titular Companions. Though the actual secrets of The Bridge are never given away until the very end of the novel – masterly writing by Laura Purcell, to protract the mystery to that length! – the possibility always remains, mainly due to Elsie’s increasingly unreliable state, that there is a psychological factor here too, the sort found in Shirley Jackon’s The Haunting of Hill House, though readers with faint hearts should take no comfort from this, as it only serves to boost the nightmare.

As a story, The Silent Companions is filled with fascinating characters. No-one here is stock or run-of-the-mill, not even lesser characters like the two maids, Helen and Mabel, who provide realistic portrayals of churlish and impudent ex-workhouse girls, while housekeeper, Edna Holt, instead of being a typical trusty stalwart of the older staff, is another difficult presence, harbouring thinly-veiled resentment of her youthful new mistress.

The book’s three leads are equally well-drawn.

Elsie herself is stronger and grittier than the average Victorian-era heroine, very much a high-handed lady of the period – dressing well, minding her manners and casually ordering her servants around – but also one who is risen from nothing and the daughter of abusive parents. Her father a factory-owner, she grew up amid the smoke and ashes of London’s industrial quarter, an early life from which she bears both mental and physical scars – which, in its turn, has marooned her somewhere between the two worlds of the establishment and the underclass, meaning that she’s able to draw friends and allies from neither. This has toughened her, of course, though not to a silly degree. Elise is a feisty woman by the standards of her time, but when the haunting at The Bridge commences, she wilts like all the rest.

This is all in stark contrast to Sarah Bainbridge, Elsie’s ‘Plain Jane’ cousin-in-law, and a neurotic, self-pitying individual, who, convinced that she has been left on the shelf, cuts a pathetic figure in whose support Elsie simply can’t trust. Of course, as is regularly the case in this novel, the still waters that are Sarah Bainbridge could run deceptively deep.

Anne Bainbridge meanwhile, the mistress of the house in the 17th century, is a different animal again. A beautiful and respected lady-of-the-manor, she dominates her immediate world with an authority that Elise could only dream of, but nevertheless lives in dread of her even more powerful husband, Josiah, to the point where she can barely raise an objection to his callous mistreatment of their ‘faerie child’, Hetta. She also fears God, certain that he will plunge her into Hell for those dabblings in the dark arts, and perhaps even more so, His servants on Earth – the witchfinders – who will punish her equally severely if her tricks are discovered. Anne, the second most important character in The Silent Companions, is another mother caught between two opposing forces, and another commanding presence who in the end wields such little real command that her world will be consumed by elemental forces beyond her control.

I don’t want to say too much more about The Silent Companions, because this is a book of very well-kept secrets, which will intrigue and enthrall you as much as frighten you, and keep you guessing to the very last page. Suffice to say that the two strands, both the 17th century and the 19th century stories, while running parallel to each other, dovetail repeatedly and perfectly, in the end creating a single narrative which is presented to us in the most sumptuous, readable prose, and filled not just with eeriness, but with moments of spectacular terror.

Overall, one of the most satisfying ghost stories I’ve read in quite a long time.

As always at the end of one of my reviews, I’m going to do my bit to lobby for a TV or film adaptation by nominating the cast I would choose should such a fortunate circumstance arise … and given the dearth of recent Ghost Stories for Christmas productions by the BBC, there ought to be a vacant slot on the horizon soon! So, here we go; feel free to disagree or agree, as the mood takes you.

Elsie Bainbridge – Tamsin Egerton

Anne Bainbridge – Christina Cole

Sarah Bainbridge – Lily Cole

Josiah Bainbridge – Ben Barnes

Jolyon Livingstone – Freddie Highmore

Dr. Shepherd – Bill Nighy

Edna Holt – Penelope Wilton

One of the most important characters in The Silent Companions is undoubtedly Hetta Bainbridge, but as she’s a very young child, it would be well beyond my ability to find someone adequate for the role. So that’s one part I’ll happily leave to the official Casting Director (he or she will doubtless be glad to know).

Outline

Nothing is going right in the life of Professor David Ullman. He’s an expert in demonic literature, in particular Milton’s Paradise Lost, but he’s also an atheist, so he gets no spiritual fulfilment from this. In addition, his home life is a mess, his marriage falling apart and his 12-year-old daughter, Tess, suffering from depression. Then he learns that his best friend, Elaine O’Brien, has been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

In an effort to get away from it all, Ullman accepts a curious invitation to travel to Venice and bring his expertise to bear on “a phenomenon”. Taking Tess with him, he embarks on what he hopes will be a short but welcome holiday. However, the phenomenon turns out to be the apparent and rather horrible possession of an unknown man in a dingy backstreet house. Bewildered and distressed, Ullman returns to his hotel, only to find Tess in a similar condition, standing on the roof. Before he can intervene, she throws herself into the Grand Canal, screaming two words: “Find me!”

When the police search, no body is recovered. But Ullman saw the incident with his own eyes, and is certain his daughter is dead. He returns to the States, devastated, but soon embarks on a mission to learn more about the evil spirit he confronted in that grubby old house.

So begins a journey from religious denial to religious conviction for David Ullman. And it’s a very arduous journey indeed, a demonic entity that he’s only previously encountered in fictional work leading him from pillar to post across North America with a series of complex clues. It’s also a journey he must make with an extremely dangerous man on his heels, a proficient killer who calls himself ‘George Barone’ after a famous Mafia hitman. Whoever this guy really is and whoever’s paid him to pursue Ullman are details that remain elusive for the time-being. All that matters initially is Ullman surviving and unravelling the devilish puzzle that has been laid in front of him in the seemingly vain hope that, at the end of it all, he might find Tess, and that she might – just might! – still be alive …

Review

In some ways, The Demonologist is more like a road trip than a horror novel, but be under no illusions. For all its arthouse trappings, it is a horror novel, and in some ways a very traditional one. It’s not even low on gore – there are killings aplenty, while the demon, when it appears, will be very familiar in its motives and manners to those imagined by orthodox religious folk.

And ultimately, at least at subtext level, that’s what this is all about: a soul’s voyage from darkness to light. It’s been suggested that in some ways it mirrors Satan’s journey in Paradise Lost; he too clawed his agonising way out of the pit, though in his case there was no chance of redemption at the end.

David Ullman is a strange kind of hero – somewhat stiff, somewhat stuffy, quite superior on some occasions, and yet vulnerable and uncertain in others (he’s been dealt a pretty crappy hand, after all!), and for much of the time in this book, he’s terrified, relying on intellect rather than raw courage. For all that, he’s a nice guy in his odd, introspective way. So you can’t help but root for him along every inch of his difficult path.

I personally wasn’t terrified by The Demonologist, even though I first noticed it in various ‘top 10 scariest novels’ lists. But I was intrigued and pleasantly unnerved (the hitman is in many ways your very worst nightmare – an utterly cold, completely unemotional professional murderer), and once I got into it, I found it a damn good read. It’s taut, tense, and while it might not keep you awake at night, it will certainly keep you turning the pages.

As usual, just for fun, here are my picks for who should play the leads if The Demonologist someday makes it to the screen (I’ve heard that a movie version is in development, but we’ll have to wait and see):

Professor David Ullman – Brian Cranston

Elaine O’Brien – Mayim Bialik

George Barone – Viggo Mortensen

Outline

DS Harri Jacobs is a cop on the edge.

Okay, lots of police fiction likes to adopt that attitude, but in this case, author Danielle Ramsay really means it. Her central character has been through an ordeal the likes of which few people would recover from. A Newcastle girl by origin, she joined the Metropolitan Police in London, during the course of which service she was attacked and raped with such ferocity that she almost died. Before abandoning her broken body, her anonymous assailant made things even worse by promising her that one day he’d return and finish the job.

As part of her effort to get over this nightmare – not least because, somewhat outlandishly, she suspected that one of her London colleagues, DI Mac O’Connor, was the culprit – Harri transferred to Newcastle, feeling more at home in familiar surroundings. But even then – and this is where the novel actually starts, she is increasingly frightened and paranoid. It hardly seems likely that her attacker will follow her north, but while Harri is a strong, tough character, she is deeply damaged psychologically, and finds that she can’t trust anyone. Not only that, she keeps her new colleagues at arm’s length. In the case of wideboy DC Robertson, it’s perhaps understandable, because he’s a total throwback, but DI Tony Douglas is one of the good guys, and yet Harri is equally cool with him. And after all that, at the end of each trying day, she goes back home to an upper apartment in an otherwise empty industrial building, where she barricades herself in, so increasingly unnerved by the all-encompassing darkness that she sits with her back to the door and a baseball bat in her hand.

Of course, none of this self-imposed isolation really prepares her for the ultra-difficult days that lie just ahead.

A series of horrific crimes commences, when a young woman is found murdered and ghoulishly disfigured. We, the readers, know who is responsible; we don’t know his identity, but we’ve seen him at work in his homemade surgical lab, where he coldly, clinically, crudely, and in eerie, concentrated silence, performs torturous reconstruction on helpless and brutalised female captives. We realise, without needing to be told, that the body already discovered will only be the first of many.

All of this would be difficult enough for the cops to deal with, but Harri’s own troubles are about to get a whole lot worse. Not only has the first victim been left at a deposition site which has personal meaning for her, but she then becomes the recipient of information connecting this latest atrocity to the attack that she herself suffered (including, very alarmingly, photographic images). Convinced that it’s the same perpetrator finally coming back for Round Two, Harri knows that if she was to hand this new intel to her bosses, she’d immediately be taken off the case – and she cannot stand that thought. She’s only just regained control of her life, and to lose it again, so soon – to the same heinous villain – would be more than she could bear.

And so begins one of the most difficult enquiries that any police officer, fictional or otherwise, has ever embarked on, the killer behaving ever more monstrously, Harri agonised with guilt about withholding key evidence from the rest of the team, but determined to stay on the case, because unless she is the one to take this fiend down, she knows that she’ll never have peace, and will never be able to live with herself …

Review

In the modern era, there is an increasingly thin line between crime fiction and horror, and in The Last Cut, Danielle Ramsey crosses it several times. Make no mistake, this story centres around a truly horrific concept.

Conceive, if you can, of a serial killer who abducts his victims, straps them down in the dark and the cold, and then literally goes to work on them over a period of days, if not longer, gradually transforming them through non-anaesthetised surgery into a completely different kind of creature. Scalpels, needles and acid are all applied liberally. He even replaces their eyes with glass baubles, so that in the end only featureless monstrosities remain.

Danielle Ramsay doesn’t lay it on hard in terms of obscene detail, but again, it’s the bone-chilling concept. If you tried to put that idea alone into a movie, it would be 18-rated for sure.

The horror movie atmosphere doesn’t end there, either. The Last Cut isn’t just about a deranged killer and his nightmarish MO. It’s also about the state of heroine, Harri Jacobs’s mind. This is without doubt one of the most effectively traumatised lead-characters I’ve encountered in a crime novel to date. Primarily, that’s because it’s not in the reader’s face, but it’s there nevertheless, lurking constantly in the background.

Harri, as we’re told from the outset, it a rape survivor. Though, in many ways, she hasn’t survived at all. Her intense conviction that the madman who attacked her is not only still out there, but still stalking her, and even murdering other women in the most elaborate, grotesque ways in order to get at her, clouds her thinking to the point where she withholds essential info from her superiors, misjudges fellow officers (almost fatally at one point), and is driven to live like a recluse in a semi-derelict former factory with only a single, heavy-duty lift connecting her residence to the rest of the world.

This excellent latter device is itself hugely effective in creating a sense of fear and alienation. Harri is a lonely soul even during the day, when she’s on duty. She is so convinced that indifference to her plight lurks on all sides that she takes desperate, dangerous measures to ensure that she is kept on the case, which segregates her massively. But at nighttime, this sense of paranoia literally takes physical form. She blockades herself into this terrible old building, which creates a siege mentality, thanks to which she gets almost no rest.

The mere thought of this is blood-curdling. How would you react if, in the darkest part of the night, you heard movement on the other supposedly empty floors? How would you respond if you suddenly heard the lift ascending in the early hours of the morning – and indeed how does Harri respond?, because yes, you guessed it, that’s exactly what happens.

This is all tremendously effective in creating a dark, ultra-grim police novel.

The authentic Newcastle setting is desolate and gloomy, and again in horror fiction fashion, maintains a subtle but ghostly aura. We’re so focussed on the tight, tense interplay of the central characters that we see very little of the cty’s day-to-day life or its general population (aside from those among them who die so horribly – one gruesome event on the Tyne Bridge lingers long in the memory), so the whole of Tyneside is there, but mostly as a spectral backdrop.

Danielle Ramsay obviously loves her native Northeast, but this is a stark portrayal of the difficulties faced by police teams in the heart of an unfeeling city, especially when they are confronted by particularly violent crimes. It also reminds us that police officers themselves are only human, and likely to be damaged by many of the things they see and do – and quite often are not always the best judges of their own situations.

An intense, brooding psycho-thriller, gritty and dark as hell, and built around a disturbing but intriguing mystery. You can’t afford to miss it.

As I say, I would love to see The Last Cut get the film or TV treatment, even if it could never be sceened after 9pm (not that that would worry me). On the off-chance it will happen, and I so hope it does, here are my picks for the leads:

DS Harri Jacobs – Emily Beecham

DI Tony Douglas – Robert Glenister

DI Aaron Bradley – William Moseley

DI Mac O’Connor – Christopher Fulford

DC Robertson – Anthony Flanagan

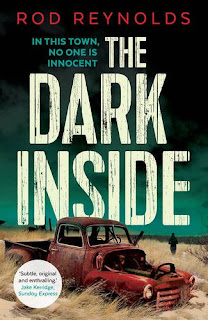

THE DARK INSIDE

by Rod Reynolds (2015)

Outline

We commence proceedings in the newsroom of the The Examiner newspaper, New York, in 1946, where we meet long-serving newshound, Charlie Yates. At first glance, Yates is an unimpressive specimen, who, though he has fifteen years experience investigating and writing about crime, was injured out of the armed forces by a road accident before he could be sent overseas (which some folk feel worked out rather well for him), and now has anger-management issues that have put paid to his marriage and regularly enrage his equally ill-tempered boss.

After one particular incident in the office, Yates, his career hanging by a thread, is sent south to Texarkana, the twin cities that straddle the Texas-Arkansas border, where a series of gruesome fatal attacks are underway, young couples accosted by a hooded gunman in remote areas and shot, the women then sexually mutilated.

It’s a lurid case, the killer referred to locally as ‘the Phantom Slayer’, but Yates still considers it small potatoes and is infuriated both to have been landed with such a story in the first place and to have been sent out here to what he considers the boondocks, to cover it.

Ironically, the boondocks are equally unhappy to have him.

Though he puts up in the Mason Hotel, along with the rest of the press pack (because despite Yates’ frustration, this is fast turning into a big story!), he isn’t received well at the Chronicle, the local newspaper, which is owned by the same company as the Examiner and thus somewhere he’d expected to find allies. Neighbourhood crime reporter, Jimmy Robinson, something of an unstable character himself, views their guest as an arrogant interloper, while Chronicle editor, McGaffney, is less overtly hostile but evidently discomforted to have a big-city crime writer on the patch.

Despite being advised that Texarkana is not New York and that these murders actually mean something because almost everyone in town has been personally affected by them, Yates goes in feet-first, asking bullish questions of all and sundry, which brings him into near-immediate conflict with lead-investigator Sheriff Horace Bailey and his enforcer-in-chief, the ultra-menacing Lieutenant Jack Sherman, who warns him off subtly but in no uncertain terms.

Yates’ suggestion that the killer may be a deranged ex-GI gains no traction with anyone, even though the town is full of such potential suspects, hordes of demobbed men, many still trigger-happy, filling the town’s bars and flocking to work at nearby Red River Arsenal, a military supply depot where their expertise would be valued, but which is currently in the process of being acquired by the town’s most prominent citizen, millionaire Winfield Calloway, throwing its future into the balance.

As the body-count mounts, the town turning ever more volatile and the dogged Yates’ relationship with both the local press and police becoming so strained that the latter soon go from warning him to making open threats, he inveigles his way into the hospital to speak to 17-year-old Alice Anderson, thus far the only survivor of a Phantom attack. He finds her upset and confused, claiming no real memory of what happened but insisting that the police have been leaning on her, trying to put words into her mouth. Afterwards, when the cops release an official statement that Alice Anderson has described her assailant as a black man, Yates knows it for a lie.

Not long after this, a huge reward is offered, which Yates realises is going to lead to violence and intimidation against the local black community, while the real culprit is not only going unpunished but, for some reason, not even being pursued … maybe is even being protected.

Unsure who to trust, he tries to win the confidence of Lizzie Anderson, Alice’s attractive and adversarial older sister. However, Lizzie’s a woman of secrets too, and initially doesn’t seem to like him, never mind trust him. But then, bewilderingly, Alice disappears from the hospital, apparently without trace.

Against an ever-deepening mystery and in an atmosphere of simmering violence, Lizzie has no option but to turn to Charlie Yates, and Yates to her. Both feel the entire town is now ranged against them, including the killer who strikes by moonlight, the one they call the Phantom …

Review

The ‘Moonlight Murders’ that occurred in Texarkana in 1946 were a dreadful series of actual events, which saw five people killed and three others seriously wounded at the hands of an unknown killer dubbed ‘the Phantom’ because of the terrifying white hood he always wore. It’s one of the the most fascinating aspects of The Dark Inside that Rod Reynolds follows this grim, real-life history very closely indeed, even using the genuine locations of murder scenes like Spring Lake Park and Red River Army Depot. That said, he changes the names of the victims and the law enforcement officials charged with finding justice for them, and of course, purely for dramatic purposes, adds heaps of local corruption, whereas in reality there was no suggestion of such.

Of course, this isn’t the first time the legendary crime spree has been fictionalised.

In 1976, Charles Pierce made the notorious exploitation movie, The Town that Dreaded Sundown, which also told the tale but took liberties with many of the facts, suggesting, for instance, that one of the Phantom’s female victims was killed with a musical instrument, which definitely never happened and yet thanks to the movie became canon among teenagers interested in the case. Despite being vividly done, The Town That Dreaded Sundown barely rates a mention among worldwide horror movie fans these days, but it so plucked at the nerve strings of Texarkana residents that, even now, it regularly receives late-night open air screenings in Spring Lake Park.

The upshot of this (not to mention the fact that sundry other books have been written about the case, both fictional and non-fictional) is that it was never very likely Rod Reynolds would be accused of showing bad taste by dramatising these astonishing events, which I personally am more than happy about because I found The Dark Inside a thoroughly engrossing piece of grown-up thriller fiction, populated by completely convincing characters and speeding through a series of hairpin twists and turns that constantly threw me and left me eager to know what was coming next. To call this one a page-turner is not just hyperbole.

Charlie Yates makes for an excellent lead. He’s now gone on to star in two other novels, Black Night Falling and Cold Desert Sky, but this is his first appearance and it’s a powerful one, though the author set himself no small task birthing a hero who is flawed for all the wrong reasons: a guy deeply embarrassed and self-recriminating about his cowardice during World War Two, frustrated about his failures as a husband and a man, and when he first arrives in Texarkana, self-centred, aimless and drifting. Uninspired and mostly unrepentant, about the only thing Yates has got going for him is his nose for a story, but it is this that will lead him on a path to redemption. And that’s our main narrative arc.

Yes, there is a brutal murderer to unmask, but The Dark Inside is also about a man at his lowest ebb frantically trying to claw his way back to the light. And he only gets there incrementally, continually making bad choices and letting himself down, though that renders Yates all the more interesting to me. He’s the hero, of course, so you never quite give up on him. It’s no surprise that by the end of this book, the reader is one hundred percent behind the guy in his quest to put things right.

His relationship with Lizzie Anderson is a big part of this. Our heroine is hardly a femme fatale, beautiful and spirited, yes, but in her own way flawed as well as being tired and depressed. On top of that, she’s not at all attracted to Yates in the early stages of the narrative, and is eventually only drawn to him because it seems as if he’s the only guy she can trust.

Equally multi-layered is Rod Reynolds’ depiction of the book’s main villains, Horace Bailey and Jack Sherman in particular, both of whom hark back to that earlier age when ‘men were men’, even though in reality, as shown here, that could be quite nasty given the propensity of men like that for explosive violence. Bailey and Sherman are two characters you’re certain would kill you as soon as look at you if it suited their purpose. You only need to read The Dark Inside to be very thankful for the much more answerable law-enforcement agencies that we have today.

Other characters are also clearly drawn, Richard Davis, the town punk, and Winfield Calloway, Texarkana’s overweening patriarch (the sort of character Ed Begley would have played back in the ’50s and ’60s), providing much more than simple window-dressing, while local journalists Robinson and McGaffney are expertly cast as redneck newspaper men at least as concerned about protecting their hick town’s almost non-existent reputation as in breaking good stories.

I’ve never visited Texarkana, so I can’t comment on how authentically Rod Reynolds captures the atmosphere of the place, but in The Dark Inside he gives us a tremendously vivid picture of a functioning but self-absorbed community at a difficult time in the history of the American South: before the Civil Rights movement, with women and blacks still second class citizens, but with poverty and social problems never far from anyone’s door, and now with GIs flooding home from foreign battlefields, many traumatised, and of course all matters of dispute still deferred to the town’s ruling elite no matter how thuggish and inexperienced they may be.

This is even more remarkable because author Rod Reynolds is a Brit. So, all the more credit to him for producing this hardboiled slice of classic Southern Noir, in which the crimes are heinous, the atmosphere crackles and the characters bounce off each other like human ninepins.

The Dark Inside is a pitch-perfect period thriller, tense, claustrophobic and sweaty. It gets my very strongest recommendation.

I’m hoping that, with its taut tone and bad attitude and with the recent repopularisation of the Southern Gothic crime subgenre by such recent TV hits as True Detective and The Devil All the Time, it won’t be long before The Dark Inside hits our screens. So now, as usual, in eager anticipation of such a pleasure, I’m going to try and cast this beast. No one will listen to me, of course, but you must admit, it’s a fun exercise.

Charlie Yates – Adam Scott

Lizzie Anderson – Dakota Johnson

Sheriff Horace Bailey – Robert Patrick

Lieutenant Jack Sherman – Glenn Fleshler

Richard Davis – Jack Quaid

Winfield Calloway – Brett Cullen

Jimmy Robinson – Tommy Flanagan

McGaffney – Rainn Wilson

Outline

When a young pagan couple, Robin and Betty Thorogood, acquire an old farmhouse in rural New Hindwell, they are delighted to discover the relic of an abandoned Christian chapel in the grounds. Immediately, they launch plans to perform rituals there and to reclaim the ancient site for the ‘old religion’ by celebrating the traditional Celtic feast of Imbolc.

But of course, it isn’t going to be that simple.

To start with, Betty Thorogood – the more tuned-in of the two – senses a dark presence in the ruin and an air of foreboding in the encircling Radnor Valley. If this doesn’t worry her enough, the couple’s plans arouse the wrath of Reverend Nick Ellis, the local evangelical minister, who has brought a hellfire message to the UK from his former parish in the American South. Despite Betty’s charm and beauty, Ellis, a man with great charisma but an increasingly sinister fundamentalist agenda, manages to stir up intense local feeling against the duo – to the point where mob violence soon threatens.

Merrily Watkins, local vicar and Diocesan Deliverance Officer, a woman very experienced in tackling the occult, is sent to keep a watch on the volatile situation. But it soon becomes apparent that this is a vastly more complex and frightening problem than even she anticipated. To start with, there are several other bizarre, possibly interconnected issues in New Hindwell: eccentric lawyer JW Weal can’t seem to let go of his recently deceased wife and may well have used nefarious, if not downright evil, methods to hang onto her soul, while at the same time Merrily is disturbed by the rumour that a circle of medieval churches dedicated to St. Michael, originally built to contain a dragon lurking in Radnor Forest, may actually have been located there to entrap a demonic entity.

Above all though, the main threat to peace in this small community stems from the Rev. Ellis, who is much more than just a zealous preacher. Merrily soon comes to doubt his motives and even his beliefs, and finds his followers – who include several local people of note, including the fearsome councillor’s wife, Judith Prosser – a particularly menacing bunch, whose strict loyalty to each other may be concealing a wealth of sins, including murder. In fact, so worried is she by this gathering storm, that she finds herself siding with the pagan newcomers, though they themselves don’t make this easy for her when a whole bunch of them turns up, determined to desecrate the ancient Christian site with their Imbolc rites …

Review

A Crown of Lights is the third outing in the hugely popular Merrily Watkins series, and for my money one of the best. Not that I don’t have a couple of reservations about it.

One key issue I have with the Watkins stories overall is the central heroine’s apparent lack of conviction. It can’t be easy for her; the loss of her husband while she was still young and the hostility she seems to face at almost every turn from her know-all teenage daughter, Jane, must leave her feeling pretty friendless at times. But even so, Merrily, while not exactly beset with doubts about her faith, is hardly the sort of muscular Christian you’d normally expect to occupy the role of exorcist. She doesn’t seem to like anything about her own Church, and nor is she easily convinced that supernatural forces exist (despite much evidence to the contrary in this series).

That said, these apparent weaknesses work in her favour in this particular outing, as the powers soon ranged against her – from all sides, both pagan and Christian – leave her more embattled than we’ve ever seen before, which quickly wins her over to the readers. You always tend to root for the underdog, especially if she gets bullied as often as Merrily does – one scene in particular, when she is unwillingly drawn into a live TV debate with a bunch of militant witches under the control of arch manipulator Ned Bain, has you on her side in no uncertain terms.

Less easy to reconcile is the other issue, which is Phil Rickman’s general reluctance to plunge fully into the world of the weird. There are several ghostly and demonic elements in A Crown of Lights, though it is essentially a clever and absorbing murder mystery, so they remain on the periphery. This is a personal viewpoint of course, but while this subtle combo of thriller and chiller has worked for some, I found the many signposts to the arcane – the ancient churches, the legends, the folklore, the prehistoric monuments with which the wild landscape is littered, the hints of a devilish presence, etc – disappointing, as there is no real fulfilment of that particular promise.

However, this is still an excellent read.

To start with, the incendiary atmosphere in the village is hugely well handled. You wouldn’t normally expect the wintry Welsh Marches to play host to a furious war of words between fanatical religious groups, but it happens here in completely convincing fashion, the hostility simmering throughout the book until the threat of violence feels so real that you can’t help but shudder – there is surely nothing more frightening in both fiction and non-fiction than lynch-law.

It also helps to drive the narrative along that it’s such a multi-stranded mystery, which you simply have to get to the bottom of. A Crown of Lights is an intricate tale, at times almost overwhelmingly so, but it’s massively intriguing – and the reader can rest assured that it all gets tied up neatly at the end.

As always with Phil Rickman’s books, the writing is of the highest order. The gorgeous rural region is beautifully realised, its ancientness and mystery (my earlier comments notwithstanding) evoked in loving fashion. By the same token, the book is a mastery of research. The complex mythology of the Marches is brought vividly to life, while the pagan belief system is richly detailed and made to feel like so much more than silly superstition.

Most interesting of all, though, is the clash of cultures.

Paganism is portrayed as a free-spirited faith, only loosely based on genuine pre-Christian beliefs but unfettered by modernism, unlike Merrily’s ‘rational’ brand of 21st century Christianity in which the exorcist is expected to know as much about psychiatry as doctrine. And this is another key aspect of the book: the war between the old and the new – some of which rages inside Merrily, and between her vision of a kinder Christianity and Nick Ellis’s fire and brimstone, but also out in the wider village community of New Hindwell, which, though it’s hardly the back of beyond, is beset with tradition and was never likely to welcome changes enforced on it by outsiders.

A compelling, thought-provoking novel, very, very readable and highly recommended for lovers of both mystery and mysticism.

As usual – purely for fun, you understand – here are my personal selections for who should play the leads if A Crown of Lights ever makes it to the movies or TV. Thanks to that fine writer, Stephen Volk, Merrily Watkins has already bestridden our television screens in Midwinter of the Spirit, but that was then and this is now, and only a couple of those characters play a role in Crown, so, with the exception of Sally Messham, this is a different cast:

Merrily Watkins – Rachel Weisz

Nick Ellis – Billy Bob Thornton

Judith Prosser – Catherine Zeta-Jones

Ned Bain – Hugo Weaving

Jane Watkins – Sally Messham

Betty Thorogood – Sophie Cookson

Robin Thorogood – Nikolaj Coster-Waldau

JW Weal – Robert Pugh

(I know, I know … this would be an expensive line-up, but in my imagination I have limitless funds, so yah!)

Outline

Liverpool in the depths of December. Christmas is approaching, but there is little joy to be had in the Sefton Park district of the wintry city.

DCI Eve Clay and her team of experienced homicide investigators are baffled and horrified when they are called to the murder of retired octogenarian college professor, Leonard Lawson, an expert in medieval art. To make the case even more disturbing, Lawson, who was ritually slaughtered inside his own home and then fastened to a stake in the fashion of a game-animal, was discovered by his daughter, Louise, an ageing and rather fragile lady herself, who is so shocked by the incident that she can barely even discuss it.

This resolute silence, whether it’s a natural reaction to the horror of the incident, or something more sinister – and Clay is undecided either way – impedes the police, who are keen to delve into the victim’s past, not to mention his current circle of acquaintances, to try and work out who might harbour such a grudge that they would inflict such sadistic violence on him.

At least Clay can call upon a considerable amount of expertise. DS Bill Hendricks is her strong right-arm, and a no-nonsense but deep-thinking copper who knows his job inside out. DS Gina Riley is the softer face of the job, another experienced detective but a gentle soul when she wants to be, and very intuitive. Meanwhile, DS’s Karl Stone and Terry Mason are each formidable in their own way, as are the various other support staff the charismatic DCI can call upon.

With such power and knowledge in her corner, it isn’t long before Clay is making progress, a matter of hours in fact, though the mystery steadily deepens, leading her first to a care home for mentally disabled men (including the likeable, innocent Abey), and yet run by the non-too-pleasant Adam Miller and his attractive if weary wife, Danielle (who may or may not be more than just a colleague to the young, modern-minded carer, Gideon Stephens).

Yes, it seems as if there are mysteries within mysteries to be uncovered during this investigation. However, Clay and her crew continue to make ground, finally becoming interested in Gabriel Huddersfield, a disturbed loner who haunts the park and makes strange and even menacing religious speeches, and being drawn irresistibly towards three curious if time-honoured paintings: The Last Judgement by Hieronymous Bosch, and The Tower of Babel and The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel.

These garish Renaissance masterpieces were all regarded at the time, and by modern scholars, as instructions for the benefit of mankind, giving warnings about his fate should he stray from the path of righteousness, each one incorporating terrifying and brutal imagery in order to deliver its fearsome message.

But even though these objects inform the case, and Clay and her team soon develop suspects, the enquiry continues to widen. What role, for example, does the rather strange character who was the late Professor Noone have to play in all this, and what exactly was the so-called ‘English Experiment’? All we know about it initially is that it wasn’t very ethical and that it somehow involved children.

Clay herself becomes emotionally attached to the case, its quasi-religious undertones affecting her more and more, because, as a childhood orphan, she was raised by Catholic nuns, though in her case – and this makes a welcome change in a work of modern fiction – it wasn’t all negative; Clay owes her empathetic nature to the love and affection she received from her guardian, Sister Philomena, while the tough but kindly Father Murphy recognised and nurtured the spark of leonine determination that would go on to gird her greatly for the challenging paths ahead.

But all this will be rendered null and void of course if the Selfton Park murderer is not apprehended quickly. Because, almost inevitably, he now strikes again, committing two more equally horrific ritualistic slayings.

Clay and her team find themselves racing against time to end this ghastliness, a race that takes them into and around some very notable Liverpool landmarks, the city’s two great cathedrals for example, and all along the snowy, slushy banks of the Mersey (all of which are generously mapped out for us). And all the while, they become ever more aware that this is no ordinary level of depravity they are dealing with. Nor is it necessarily the work of a single killer. Who, for example, is ‘the First Born’, and who is the ‘Angel of Destruction’? Whoever these ememies of society actually are, however many they number, and whatever their crazed, fervour-driven motives, it soon becomes apparent that they are just as likely to be a threat to the police hunting them as they were to those victims they have already butchered …

Review

Dead Silent is the second Eve Clay novel from Mark Roberts, and a pretty intriguing follow-up to the original outing, Blood Mist.

From the outset, the chilly urban setting is excellently realised. You totally get the feeling that you’re in a wintry Liverpool, the bitter cold all but emanating from its pages, the age-old monolithic structures of the city’s great cathedrals standing stark and timeless against this dreary backdrop, the gloomy greyness of which is more than matched by the mood; the murder detectives certainly have no time for the impending fun of Christmas as they work doggedly through what is basically a single high-intensity shift, pursuing a pair of truly malign and murderous opponents.

And that’s another vital point to make. Dead Silent is another of those oft-quoted ‘page-turners’, but in this case it’s the real deal – because it practically takes place in real time.

The enquiry commences at 2.38am on a freezing December morning, and finishes at 8.04pm that night, the chapters, each one of which opens helpfully with a time-clock, often arriving within a few minutes of each other. This is a clever device, which really does keep you reading, especially as almost every new chapter brings another key development in the multi-stranded tale.

If this sounds as though Dead Silent is exclusively about the enquiry, and skimps on any additional drama or character development, then that would be incorrect. It is about the enquiry – this is a murder investigation, commencing with a report that an apparently injured party is walking the streets in a daze, and finishing with a major result for the local murder team (and a twist in the tale from Hell, a shocker of an ending that literally hits you like a hammer-blow!), with very few events occurring in between that aren’t connected to it. However, the rapid unfolding of this bewildering mystery, and the warm but intensely professional interplay between the various detectives keeps everything rattling along.

Because this is a highly experienced and very well-oiled investigation unit, each member slotting comfortably and proficiently into his or her place, attacking the case on several fronts at once, and yet at the same time operating as a super-efficient whole, of which DCI Eve Clay is the central hub.

Of course, this kind of arrangement is replicated in big city police departments across the world, and is usually the reason why mystifying murders are reported on the lunchtime news, only for the arrest of a suspect to be announced by teatime. As an ex-copper, it gave me a real pang of pleasure to see one of the main offenders here, a cruel narcissist and Pound Shop megalomaniac, expressing dismay and disbelief when he learns how quickly he is being closed down.

And yet, Mark Roberts doesn’t just rush us through the case. He also gives himself lots of time to do some great character work.

As previously stated, Eve Clay is the keystone, the intellectual and organisational force behind the team’s progress, but at the same time, while a mother back at home, also a mother to her troops, someone they can confide in when they have problems, but also someone they have implicit faith will lead them from one success to the next. What is really fascinating about Clay, though, is the way her difficult childhood in a Catholic orphanage has strengthened her emotionally and gifted her with a warmth the likes of which I’ve rarely seen in fictional detectives (and which, at times, is genuinely touching). She makes a fine if unusual hero.

To avoid giving away too many spoilers, I must, by necessity, avoid discussing the civilian characters in the book, except to say that Mark Roberts takes a cynical but perceptive view of the kind of people police officers meet when investigating serious crime.

Ultimately, all those involved in this case, even if only on the periphery, are abnormal in one way or another, while those at the heart of it … well, suffice to say that some kind of insanity is at work here. Because surely only insanity, or pure evil, or a combination of both, can lie at the root of murders like these. Roberts investigates this wickedness to a full and satisfying degree, completely explaining – if not excusing – the terrible acts that are depicted, and yet at the same time using them to underscore the dour tone of the book. Because there is nothing particularly extravagant or outlandish about the villains in Dead Silent, even if they do commit horrific and sadistic murders. They may be depraved, but there is still an air of the kitchen sink about them, of the mundane, of the self-absorbed losers that so many violent sexual criminals are in real life – again, this adds a welcome flavour of the authentic.

To finish on a personal note, I also loved the arcane, artistic elements in the tale. Again, I won’t go into this in too much detail, but I’ve long been awe-stricken by messianic later-medieval painters like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. Though replete with multiple meanings, their lurid visions of Hell and damnation, of a world gone mad (or maybe a world born mad!), are among the most memorable and disturbing ever committed to canvas. It’s distressing to consider that such horror derived from men of artistry and intellect, but then to see these ancient atrocities interwoven with latter-day insanities like the English Experiment (which again has emerged from men with talent and education!), is fascinating, and gives this novel a richness of aura and depth of atmosphere that I’ve rarely encountered in crime fiction.

Read Dead Silent. It’s a class act.

And now, as always at the end of one of my book reviews, I’m going to be bold (or foolish) enough to propose a cast should Dead Silent ever make it to the screen, though most likely that would only happen if Blood Mist happened first. Nevertheless, here are my picks:

DCI Eve Clay – Claire Sweeney

DS Gina Riley – Tricia Penrose

DS Bill Hendricks – Liam Cunningham

Danielle Miller – Cathy Tyson

Adam Miller – Paul McGann

Gideon Stephens – Tom Hughes

Louise Lawson – Alison Steadman

Leonard Lawson – Malcom McDowell

DS Karl Stone – Stephen Graham

DS Terry Mason – Joe Dempsie

Gabriel Huddersfield – Luke Treadaway

Abey – Allen Leech

A brand new sex killer is terrorising Glasgow, dumping and displaying his ‘party girl’ victims in ritualistic fashion in the city’s various Gothic cemeteries.

A seasoned but dysfunctional murder investigation team swings into action, aided and abetted by young crime scene photographer, Tony Winter. But this will be no straightforward enquiry. Retired detective Danny Neilson – Tony’s uncle – is convinced he’s seen this maniac’s hand before. Back in the ’70s, he hunted a Glasgow rape-strangler known as Red Silk, who also picked his victims up in bars and nightclubs. The problem is, the Red Silk murders were eventually pinned on another Scottish serial killer Archibald Atto – and Atto is still inside, serving a full-life sentence.

So what’s going on? Did the original Murder Squad get it wrong? Is this a copycat murderer? Or a student of Atto perhaps? One question definitely needs answering – how is it that Atto, all but incommunicado in the isolation block, knows so much about this latest batch of heinous crimes? …

Review

I have all kinds of reasons to recommend his novel. A Glasgow native, Craig Robertson brings the wintry city to life in glorious, gritty form, using lots of real locations, and painting a vivid picture of its lively and street-smart population – both as it is now, and as it was in the sectarian early ’70s. He also knows his local history, because this fictional case is clearly influenced by the unsolved Bible John murders of the 1960s, a dark chapter in Glasgow’s history, which continues to haunt many of those who remember it.

The police enquiry itself is excellently handled and worryingly authentic – there are lots of stresses and strains in the team, not to mention inopportune moments of realistic error-making, while the sheer griminess of its members’ daily experience has had a brutalising effect on them. There is little love lost here, and almost no political correctness, especially where hard knut boss DI Derek Addison is concerned, but none of this matters because this is not the nice, safe world so many of us inhabit – it is dark, bleak, dangerous, and at the risk of sounding clichéd, the wolves that scour it will only be brought down by wolves of a similar nature.

Robertson is also known for his character work, and it’s never been better exemplified than it is here. Winter himself is a flawed hero, his fascination with the artistry of violent death leaving him open to the wiles of Atto, who, during the course of several tense interviews, starts to recognise a like mind in the young snapper. This makes it all the more difficult for Winter’s on-off girlfiend, DS Rachel Nary, who might once have been the warm heart of this investigation unit had she too not been battered by life. For me though, the star of this show is Danny Neilson, who we see in two parallel narratives, as he was when still a carefree lad-about-town copper back in 1972, and as he is now, old, overweight, grouchy, constantly trying to patch up his many failed relationships, and at the same time obsessed with the case he never managed to solve.

So yeah … this is a bit of an ensemble job, with several lead characters, all of whom go on dark if fascinating journeys. And all the time of course, in the background, the clock ticks down to yet another vile murder.

I’ll say no more except that it’s a tour-de-force. If you like your urban crime fiction grimy, and you enjoy looking a little more deeply into the lives and loves and hates and fears of those caught up in it, then this one is definitely for you.

As usual, just for the fun of it, here are my picks for who should play the leads if Witness The Dead were ever to make it to the screen:

Tony Winter – James McAvoy

DS Rachel Nary – Karen Gillan

Danny Neilson – Brian Cox

Archibald Atto, Red Silk – Ciaran Hinds

DI Derek Addison – Dougray Scott

SLEEP NO MORE

by LTC Rolt (1948)A newly-reissued single collection of British ghost stories from an author not primarily associated with the supernatural genre, but a book with a long reputation in the field, particularly among fans of Jamesian-style ghost fiction, for being a forgotten classic.

Before we assess the book in closer detail, here is the publishers’ own description of its contents:

This powerful collection of stories of the supernatural combines LTC Rolt’s writing talent with his unparalleled knowledge of Britain’s industrial heritage to produce tales of real mystery and imagination. This haunting anthology takes the reader on a journey from Cornwall to Wales and from the hill country of Shropshire to the west coast of Ireland.

‘The House of Vengeance,’ set in the Black Mountains of South Wales, tells what happens when a walker becomes lost and disorientated as the mist falls, while in ‘The Gartside Fell Disaster’ an old railwayman recounts the terrible night when the ‘Mountaineer’ came to grief. Alongside these are twelve other tales of elemental fears and strange and inexplicable happenings.

First published in 1948, this enduring collection will appeal to all those who, like Tom Rolt, are passionate about the backdrop of our industrial landscape and will delight and terrify anyone who loves a good old-fashioned ghost story …

Lionel Thomas Caswell Rolt (1910-1974) was best known during his lifetime as a trained engineer who turned his hand to writing on engineering and industrial matters, and, most famously, to producing well-regarded biographies on the two great pioneers of that field, Thomas Telford and Isembard Kingdom Brunel. He was also renowned for his interest in and knowledge of cars, trains and other vehicles, which manifested itself in his participation in vintage car rallies and the development of heritage railways, as well as for being a narrow boat enthusiast and a major promoter of leisure cruising on Britain’s inland waterways.

What there was no outward sign of was his fascination with ghost stories, particularly the ghost stories of MR James, which were characterised by atmospheric old English (or old European) locations, gentleman scholar protagonists, and malevolent spectral foes invoked through their attachment to mysterious and arcane artefacts or locations. Bearing this in mind, and that Rolt was also a close friend to Robert Aickman, a fellow conservationist and a founder member of the Inland Waterways Association (which restored Britain’s by then semi-derelict canal system) but best known today as an author and very accomplished practitioner of the English weird tale, it may be less of a surprise that in due course the one-time engineer also penned a bunch of ghost stories.

Sleep No More was first published by Constable in 1948, and was immediately well-received. But because Rolt didn’t write any follow-up collections, his standing as a ghost story writer gradually faded until by the turn of the century, for the average man on the street at least, it had more or less vanished. New small-circulation editions have since been produced by enthusiasts: Branch Line (who specialised in publishing railway books) in 1974, and the late much-lamented Ash-Tree Press in 1996 (who added two extra stories to the line-up), but both those versions are now out of print. For that reason alone, this relatively new edition (2010) from The History Press must be regarded as something of a collector’s must, but also because with a new introduction by Susan Hill, it’s a really nice piece of work in its own right.

As to whether the material it contains still works, well … it did for me.

To start with, it’s all beautifully and compellingly written. Tom Rolt couldn’t just paint pretty pictures with his words. He did it succinctly. Considering that much of his output was factual non-fiction, he also had the talent to pace his stories effectively and people them with convincing characters.

In terms of style, there is no doubt that Rolt was strongly influenced by MR James, though Rolt’s world was not that of academia or the cloister, and this is clearly represented in his tales, in many of which, though the central characters are often lonesome scholarly types on missions of discovery through the British back-country, the settings are abandoned industrial sites or places where industry or engineering is in process or has left its mark on the landscape. However, what is very reminiscent of the old master is the malign and even deadly nature of the supernatural threats, while from Robert Aickman, he appears to have inherited an intriguing habit of injecting strangeness into his stories as well, not always providing clean cut explanations for the weird and disturbing events he describes.

For that reason, some of the stories in this collection I’d regard as eerie rather than out-and-out frightening, but that’s a good thing, because that means they were affecting and left me thinking about them long afterwards.

Three of the best stories in the book fall into this category, The Shouting (one of the two later additions), Cwm Garron (which is exceptional) and Hawley Bank Foundry, but because I’m going to be discussing these three a little later on (in the movie adaptation part of this review) I won’t say too much synopsis-wise, except to comment that all three take place in otherworldly semi-rural locations, and that all hit us straight off with an indefinably doom-laden atmosphere, which steadily deepens until reaching a stark, bone-chilling denouement.

Also falling into this category is The Cat Returns, in which a car breaks down on a stormy night and the honeymooning couple inside it fight their way through the rain on foot until encountering an isolated house. A man they suspect is a servant admits them and bids them stay over, but he seems to be terrified of something … and then the phone rings. There’s a bit of a traditional ghost story vibe with this one, but again, the creepiness of the situation, almost from the beginning, is its main asset. Likewise, in World’s End, a traveller on the Pembroke Coast becomes lost in a sea fret and takes refuge in an inn, where he must share a bedroom with a man he doesn’t know and subsequently endures an appalling experience. This is another dreamlike Aickmanesque tale, with much to disturb the reader before we even consider its supernatural message.

Perhaps the most overtly Jamesian story in the book, and another of the best, is Bosworth Summit Pound. Again, I’ll be talking about this one a little more later on, so I’m offering no thumbnail synopsis, but it’s got the personal touch and perhaps the most authentic feel of them all (not that they haven’t all got the air of authenticity when it comes to the industrial heritage of Britain) as it takes the reader deep into Rolt’s beloved inland waterway system.

Also with a Jamesian aura, though in a very different way, is New Corner. This one tells the story of a 1930s land speed trial, which is continually interrupted when the new corner of the racetrack becomes subject to curious phenomena, including disturbing smells and apparitions. As with many a classic Jamesian tale, the stakes are raised drastically when one of the officials has a terrible dream, which seemingly presages an awful disaster.

Even without the shadow of Dr James lying over it, this would be a powerful and frightening ghost story, as is Agony of Flame, which follows the misfortune of two men who, during a fishing holiday in the West of Ireland, are puzzled by the lights shining nightly from a ruined castle on an island in a loch. Against their better judgement, they investigate … and pay the price for the rest of their lives.

Taking us smoothly into the realm of the more traditional non-Jamesian ghost story is A Visitor at Ashcombe, in which a successful industrialist and his wife move to a mansion in the Cotswolds and insist on opening up a forbidden chamber, where once, it is said, a celebrated witch-hunter held court. Almost inevitably, chaos and tragedy result.

Similarly reminiscent of the older, more typical English ghost story (Dickens’s The Signalman being a good example here) is The Garside Fell Disaster, in which a Victorian-era signalman reflects on the events that led to a railway accident in the tunnel where he was stationed in the wilds of Cumbria and his conviction that there’d always been something odd about that mountain. Meanwhile, in Hear Not My Steps, a professional ghost hunter takes it on himself to spend a night in a haunted room. He’s never encountered a real ghost yet, though all that will shortly change.

In Music Hath Charms, a young man inherits a coastal house in Cornwall. When he travels down there with a friend, it is in a semi-dilapidated state. It also boasts an uncanny history, and when they search among its lumber they find a curious musical box, which produces a tune the new owner falls in love with but which his friend is strangely repelled by. In The House of Vengeance (the second of the two later additions), meanwhile, young John gets lost while hiking through the Brecon Beacons to his friend’s cottage. When a fierce storm strikes, he seeks sanctuary in a curious farmhouse that is not on any map.

These more familiar types of ghost stories are perhaps slightly less impressive in terms of originality, featuring, as they do, demonic spirits, possession etc. At least, that’s the case when they’re read today. But overall this is an excellent collection of supernatural tales. It’s a superior standard of writing, often taking place in unusual settings and strange, blighted locations, and if the ambition was to produce something as intensely and lingeringly scary as MR James often was, then it’s a very worthy effort indeed.

We’ve often heard it proclaimed that such and such an author is the next MR James, and while I’ve never read one yet who was, LTC Rolt comes very close.

And now …

SLEEP NO MORE – the movie.

I doubt that any film maker has optioned this book yet, and whether or not it’s ever likely to happen, but as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my opinions just in case some major player decides to put it on the screen.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a portmanteau horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances which require them to either relate spooky stories or listen to them.

It could be that they find themselves in an idyllic country villa, where a nervous renovator needs reassurance about his various nightmares (al la Dead of Night), or maybe locked in the basement of a Thames-side tower block, where drink and the passage of time forces them each to reveal their deepest fears (a la Vault of Horror).

Without further chit-chat, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The Shouting: Edward takes a rental cottage in a quiet corner of Devon, on the edge of coastal woodlands. But he soon becomes intrigued by the strange-looking children who pass his place while making an unexplained daily trip to a curious mound of turf deep in the trees ...

Edwina (no reason why it can’t be a woman) – Ruth Wilson

Bosworth Summit Pound: Fawcett, a man in ailing health, takes a boat trip along one of England’s lesser known waterways, which he doesn’t survive. His journal, however, relates a tale of terror concerning a bone-chilling encounter in a menacing canal tunnel at the journey’s halfway point …

Fawcett – Richard E Grant

Cwm Garron: Carfax embarks on a one-man holiday in the Welsh mountains. He stays at a peaceful inn in a picturesque valley. But a fellow guest, Elphinstone, a noted folklorist, advises him that not everything here is as pleasant as it may seem …

Carfax – Matthew Goode

Elphinstone (another gender change, but no harm done) – Alison Wright

Hawley Bank Foundry: During World War II, an industrialist reopens an abandoned ironworks deep in the Shropshire countryside, and immediately there are strange goings-on: reports of phantom figures and some type of unknown vermin that infest the factory and kill the local cats …

Frimley – Ken Stott

Clegg – Liam Cunningham

by Craig Russell (2019)

Outline

Hrad Orlů is a medieval castle built on a towering crag in the mountains of the Czechoslovak Republic. For long centuries, in that archetypical style of indomitable Eastern European bastions, it has lowered over the surrounding villages, casting a dark and ominous shadow, especially as it was once the home of law-unto-himself despot, Jan of the Black Heart, whose cruelty bordered on total madness. Now, in 1935, it remains fully intact and still strikes a note of fear in those who see it, because these days it is used as an asylum for the criminally insane. Local gossip has always held that Hrad Orlů is a bad place, haunted not just by evil memories but by the souls of the dead and even infernal spirits as, supposedly, the castle was built over a system of deep caves that formed one of the entrances to Hell.

So, it’s a surprise to no one among the local peasantry that only their country’s worst murderers are incarcerated there, including the so-called Devil’s Six, a bunch of killers so violent and degenerate that they are considered unfitted for imprisonment anywhere else.

However, things are not quite so bad on the inside. Under the leadership of progressive chief psychiatrist, Professor Ondrej Romarek, the staff are dedicated to treating their inmates rather than punishing them, and all the most modern methods and equipment are in use. It is the ideal environment for young up-and-coming psychiatrist, Viktor Kosárek, who as a student of Jung, is determined to get to the very roots of the mental disturbances that have led his new patients to kill.

He arrives at the asylum at a timely moment, as a new serial predator nicknamed Leather Apron is wreaking havoc in Prague’s poorer districts, where he butchers prostitutes in the manner of Jack the Ripper. Local police chief, Captain Lukáš Smolák, an intelligent, even-handed officer, is leading the hunt but getting nowhere, and increasingly having to balance this duty with controlling disorder on the streets, as, due to the rise of Hitler, stresses are growing between the country’s native Czech and Sudeten German populations. Similar differences are emerging inside Hrad Orlů, where the asylum physician, Doctor Hans Platner and one or two others, approve of Hitler’s philosophies, though for the time being, young idealist, Viktor, is too busy on other fronts to pay much heed to this: firstly, he is slowly falling in love with hospital administrator, Judita Blochova, who, as a Jew, suffers awful nightmares about a dark age looming for her people, and secondly is keen to bring pioneering treatment, a combination of drug therapy and deep hypnosis, to the Devil’s Six.

Viktor believes in the existence of the ‘id’, a deep place inside all of us where our most violent and destructive impulses are stored, our ‘potential for evil’ for want of a more scientific phrase. He argues that when this is triggered, all manner of horrors can be enacted by even the most mild-mannered people. Viktor calls this the ‘Devil Aspect,’ and asserts that everyone possesses one, though he admits that in the case of the Devil’s Six, it has already been given full rein.

These are a dangerous group of individuals by almost any standards.

They comprise: Hedrika ‘the Vegetarian’ Valentova, who killed her husband and fed him to his own sister; Leos ‘the Clown’ Mladek, a roving child-killer who lured his victims by wearing circus makeup; Dominik ‘the Sciomancer’ Bartos, a deranged scientist who murdered people in the midst of fiendish experiments; Pavel ‘the Woodcutter’ Zeleny, who chopped his wife and children to pieces with an axe; Michal ‘the Glass Collector’ Machacek, a sex murderer who kept his female victims’ heads encased in glass; and worst of all, Vojtech ‘the Demon’ Skála, a raging madman who has committed every kind of homicide, and revels in the pain these deeds have caused.

It’s perhaps understandable that Viktor feels he has his hands full inside the asylum. But it’s increasingly looking as if his expertise will be called for on the outside as well, and maybe some proof will be required that his patients are securely locked up. Because Leather Apron continues to hit new levels of depravity as he slaughters, with Captain Smolák increasingly helpless in the face of the violence unleashed and not a little bit bewildered when one of his suspects admits to peripheral involvement but insists that the real culprit was quite literally the Devil himself …

Review

Just from looking at it, you could be forgiven for thinking The Devil Aspect an out-and-out horror novel. All the trappings are there: the Dracula-type castle; the forested, mountainous setting; the fast approach of a terrible mid-European winter; the ongoing horrific slayings (often given to us unstintingly); the plethora of terrifying legends encircling these events.

But while there is no doubt that Craig Russell has written a horror novel here, and a Gothic one to boot, it’s also much, much more than that.

At the heart of it lies the fundamental discussion about whether heinous deeds spring from the damaged psyche of human beings traumatised beyond repair or because there is a force of genuine evil in the world. Both sides of the argument are handled intelligently and accessibly, but no easy answers are forthcoming, even Viktor Kosárek forced to wonder at one point if the mental illness that causes men to murder might actually be contagious, a theory no practitioner in psychiatry has ever taken seriously (despite the mass psychosis clearly on display here), and openly and repeatedly referring to this madness as ‘evil’, a politically incorrect term which, even in the 1930s many in his profession would eschew.

Of course, all the time this is going on, we’re acutely aware that, only next door in Germany and Austria, the Nazis are rising to power, threatening a tide of blood and violence, which we, with our hindsight, already know will be perpetrated and indulged in by so many who previously led law-abiding lives that it will make any such conversation seem almost redundant.

For me, this constant awareness of time and place is a key factor in The Devil Aspect’s success.

Many historians have asked the key questions: how did the Nazis ever attain power?; why did so many non-criminal persons end up collaborating in the Holocaust? And the uniqueness of where and when it happened has often been offered by way of at least partial explanation. In The Devil Aspect, this tiny corner of the First Czechoslovak Republic is almost a microcosm of that. To begin with, it’s an isolated community, cut off by geography in this case though by ideology in the wider context, there is poverty, frustration and urban decay, violence is already commonplace, society divided along racial lines (by picking mainly on the underclass, even Leather Apron is mostly eliminating ‘undesirables’). As well as all that, religious belief is on the wane, the strictures that once forbade men from doing evil fading fast, and yet a new humanist Utopia has not arrived and so mysticism has filled the gap, not just notions of Aryan superiority, but dark legends from Slavic mythology too (I challenge anyone to find a scarier deity than Veles, the Slavic lord of the underworld).

Craig Russell also neatly reflects the ambience of Central Europe in the 1930s. From his depiction of Prague as a foggy realm of arched alleyways, narrow cobbled streets and baroque buildings, he is drawing directly on the German Expressionist movement, while the serial killers who seem to abound here are strongly reminiscent of the real-life Weimar Beasts, the succession of mass murderers, from Peter Kurten (who is referenced in the book) through to Fritz Haarman, who seemingly came from nowhere to terrorise Germany between the wars.

Okay, well that’s all very clever, but does it work as a thriller?

Well, I feel there are one or two incongruities. Dare I say it, there may be a couple too many serial killers on show, though my main concern there is that several of them felt a little like window-dressing rather than real characters, and their presence in the plot soon seemed superfluous. I also felt that of the two lead good guys, Captain Smolák was by far the more engaging, an ordinary man doing his level best to hold it all together in the midst of murder and chaos, even though he suffers a personal loss as well, while Viktor is a little wrapped up in his own intellect (though to be fair to the latter, he does become more proactive when he starts to suspect that he knows the main killer’s identity).

These are minor quibbles, though. The Devil Aspect is a majestically written and superbly atmospheric thriller, which though it condenses quite a lot of food for thought into its 475 pages, most of this is so fascinating that you just keep reading. The action sequences, of which there are several, are also damn good, while the mystery itself continues to twist and turn in that time-honoured fashion. All-round, a brooding Gothic chiller that should grace the shelves of anyone interested in truly dark fiction.

And now, as ill-advisedly as ever, I’m going to take it on myself to try and cast this thing in the event that some very smart film-maker decides to put it on the big screen. As usual, only a bit of fun, but you never know, at some point someone with big cash may take the leap. (As I’m pretty short of knowledge re. Czech-born actors, I’m here going for English speakers; you’ll just have to imagine them putting on convincing accents).

Dr Viktor Kosárek – Rami Malek

Capt Lukáš Smolák – Joaquin Phoenix

Prof Ondrej Romanek – Michael McElhatton

Judita Blochova – Emmy Rossum

Vojtech Skála – Jamie Foreman

Filip Starosta – Danila Kozlovsky

Outline