I hope you’re all getting in the mood by now. If you’re not, maybe this will help? It’s the third and final installment of my festive chiller, STUFFING.

Before you commence reading, just a quick reminder - this is PART THREE. If you want to start at the beginning, aka PART ONE, and you haven’t done that already, just scroll down to the previous two posts, You’ll find PART ONE on December 8, and PART TWO on December 16.

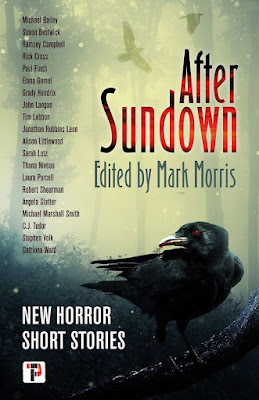

In addition to that, and because we’re on the subject of short scary stories today, I’ll also be posting a detailed review of last year’s amazing horror anthology, AFTER SUNDOWN, as edited by the indefatigable Mark Morris (I know, I know ... the bloke is everywhere at present). As always, you’ll find that review towards the bottom end of today’s post in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

But that’s for later. Before then, let’s get going with ...

STUFFING3

Max inserted an ear-bud and played back what he’d recorded. “What are you talking about?” “You can’t seriously be buying all this?” Kerry said.

“Are you kidding? This is fantastic.”

“Fantastic?”

“If nothing else, it’ll be a weird and wonderful podcast.”

“But he talks about that damn bear as if it was some kind of rival.”

Max shrugged. “In some ways it was, wasn’t it? As Cleghorn’s act waned, the bear grew popular. Think about the era. The Muppets were on telly, Basil Brush, Rod Hull and Emu. But the stand-up guys who’d started on the club circuit were fading …”

“He talks about it as if it was real. As if it was deliberately trying to undermine him.”

“Obviously that’s the way it seems to him.”

“That’s the way it would seem to someone who isn’t right in the head. How long are we staying and listening to this? The last train’s eight-thirty … we can’t afford to miss it.”

Max sighed. “What time is it now?”

She glanced at her watch. “Nearly six-thirty.”

“We’re okay yet. It’s what, eight or nine miles to the station. That’s a fifteen-minute taxi ride. We’ve got bags of time.”

Cleghorn re-entered the room, carrying a flattish cardboard parcel. Again, Kerry felt surprise. The guy was so far off the grid down here, it was difficult to imagine he could be the recipient of Amazon deliveries and such. He dropped the parcel onto the telephone table, scooped up his glass and headed back to the drinks cabinet.

“Where were we?” he said, slurring a little. “Oh yeah, the catch. That wretched bear.” He poured himself another generous measure. “Well, they weren’t getting me with that caper, I can tell you. I’d see to the bastard personally.” He plonked himself down. “There was only room for one clown on this stage, and it certainly wasn’t going to be him.”

Kerry decided that if Max didn’t soon realise they’d got everything useful they could out of this man, she’d announce it publicly. As Max consulted his notes, she stood up, crossed the room and glanced around the curtain – and was stunned to see a winter wonderland.

Those first few flakes she’d spotted earlier had only been the prelude to a snowfall so heavy that despite the relatively short time since, the front garden was already inches deep. Not only that, snow was still falling, fast and thick, and whipping on a sharp wind. So intense was it that she could barely see the main gates at the end of the drive.

“Max!” She pushed the curtain open. “We need to call a taxi immediately.”

Max got to his feet, equally surprised by the outdoor scene, and not a little disappointed. Kerry nodded at Cleghorn, who seemed oblivious to the problem. “I’m sure you’ve got enough material now, aren’t you, Max?”

“Well, I …”

“Mr Cleghorn? Max and I need to leave before we get snowed in. Thank you for your hospitality. But I’m wondering, may we use your landline?”

Cleghorn gave an indifferent shrug.

She walked to the telephone table. “I don’t suppose you know any taxi firm numbers?”

Again, a shrug. He swilled more booze. Irritated, Kerry dug through a pile of dog-eared paperwork stacked next to the phone, and with fortuitous speed, found a small card.

She placed the call, glancing at Max, who was standing around looking frustrated. He seemed to be about to raise an objection, when the call was suddenly answered.

“Eastside Cars,” came a woman’s voice.

“Can we have a taxi as soon as possible please?” Kerry replied. “We’re going to the railway station.”

“Where are you, my love?”

For half a second, Kerry couldn’t remember the address. She grabbed up the cardboard package and turned it over, only to find that it was blank. On both sides.

She tossed the package onto the sofa, and asked Max. Sulkily, he told her.

“15, Hockton Mill Lane,” she said.

“Oh, I’m sorry, love.” The tone had immediately changed. “I can’t send a car down there. Not in this weather.”

“Are … are you serious?” Kerry stuttered.

“I’ve never been more serious.”

“But we can’t be marooned here. It’s Christmas Eve. We have to get home.”

“I’m sorry, love. I’m not sending cars down that road in this weather. Last time we did that, we had two of them stuck there all night.”

As if for emphasis, the line went dead.

Kerry relayed the info to Max, who absorbed it without comment as he buttoned his overcoat. Behind him, meanwhile, Cleghorn seemed nonplussed as he turned the unaddressed package over in his hands. Presumably he hadn’t looked at it properly when picking it up from his doormat.

“Mr Cleghorn,” Kerry said. “Are there any other taxi companies in town?”

He gave her a troubled frown. “What’s that?” Before she could answer, he swung to Max. “You didn’t manage to open the shed?”

“Erm, we … well …” Max looked fazed, “we loosened the wire.”

Cleghorn’s expression changed: from sudden anxiety to outright fear. He ripped at the package, which came apart with remarkable ease, as if the cardboard was old and rotten.

“Max!” Kerry said, worried. “What’re we going to do?”

There was a low but voluble curse. They glanced round and saw Cleghorn backing away from his sofa, staring at the item he’d dumped there, though to their eyes it was no more than a heap of colourful material.

“Chriiist!” the ex-comedian finally choked. “Good Christ almighty!”

With more energy than either of them had imagined possible, he spun and lurched out of the room. A few seconds later, they heard swift impacts on the staircase.

“What was that about?” Kerry said. “He disapproves of Christmas presents too?”

“Maybe he disapproves of guests suddenly walking out mid-conversation.”

“Max!” She stared at him askance. “Look what’s happening outside!”

“I see that. But I was making headway. And now suddenly we’re going?” More out of frustration than actual interest, he grabbed up the pile of material Cleghorn had been repulsed by. “I hadn’t even got to the nitty-gritty!”

“You mean why he stopped being famous?” she said. “For God’s sake, how about he developed a fixation that a puppet was plotting against him? That isn’t revelation enough …?”

“Jesus!” Max interrupted, having opened the material out.

It was an archetypical Christmas jumper; you could tell that from the thick woollen knit, from the parallel rows of Christmas trees, skiers and reindeer heads. It was also filthy: impacted with dirt, stinking of mold. But the most noticeable thing was its size. Whichever man wore this, he’d need to be truly massive.

“This came through the letterbox?” Max asked.

“I suppose,” Kerry replied. “It’s unaddressed, so I imagine it was delivered by hand.”

He visibly paled.

“Why?”

With a thunder of footfalls again belying his age, Bernie Cleghorn descended the staircase and came back into the lounge. He’d donned a heavy mac and a scarf.

He regarded them stonily. “You were unable to summon a taxi, I gather?”

Dumbly, Max nodded.

“In which case, I’ll be glad to drive you.”

Kerry frowned. “Haven’t you been drinking?”

Cleghorn gave her a pitying look. “My dear, do you really think any police will be looking to pull motorists over on a night like this?”

“Well, yes. It’s Christmas Eve.”

A tremendous bang, a real impact this time, not some hollow thud, sounded from the rear of the house. Cleghorn jerked, but pointedly didn’t look round.

“I imagine blizzard conditions like these will make it difficult for them to judge who’s been drinking and who is simply struggling in the snow,” he said. “The thing is … I’ve decided to make a festive visit to my sister in Coventry.” He indicated a suitcase out in the passage; from the rags and tags of clothes protruding, it had been hastily packed. “Of course, if you’d rather walk …?”

“No, no, it’s fine,” Max said, with a sudden, distinct feeling that leaving wasn’t such a bad idea.

“Good.” Cleghorn went out again, heading into the depths of the house. “Just wait by the car …”

“Max!” Kerry protested. “The guy’s half-cut.”

“Like he says, we can always walk.”

He headed out into the corridor, and she had no option but to follow. At the front door, they drew the bolts back, turned the key, and stepped into a tumult of wind and flakes. Huddled and shivering, they crunched along the front of the building. On rounding the corner to the car port, the whole rear end of the vehicle had already been plastered white.

“So, the octogenarian driver’s drunk,” Kerry said. “The car’s a wreck and the conditions are horrific. What could go wrong?”

“Like I say …” Max replied. “Podcast of all time.”

She turned to him. “Why did that jumper upset you? One minute earlier, you were ready to take your chances with this storm. Now you can’t wait to go.”

He shook his head, unsure how to phrase it. “It … well, it’s got to be a joke.”

From the front of the house, the main door banged closed, and a key rattled as it turned. Cleghorn, wearing a flat cap and muffler on top of everything else, stumbled towards them, humping his case.

“Whoa!” Max shouted.

“Kerry spun back. “What?”

He stared past the Humber at the sheet of polythene, which again was flapping and rippling. “Thought … from the corner of my eye, I thought …” He told himself that he’d been mistaken. Or tried to. “Nah, it’s … silly.”

“Max, what?” “Someone on the other side of that sheet. Just a silhouette, but …”

Cleghorn arrived alongside them, his face pinched and eyes watering. “If you could move that mess off the car, I’ll get it started.” And he sidled around to the vehicle’s driver’s door, unlocked it and folded his lanky body in behind the wheel.

Max stared at the polythene again, trying hard to think his way through the bizarre events of the last ten minutes. Kerry meanwhile was scraping handfuls of snow off the car’s rear window. When she called to him, he hurried to assist, grabbing boxes, rags and other garbage, and flinging them aside. Neither had really expected the ancient car to start, but they hadn’t realised their host had even been trying when he suddenly stuck his head out again.

“You! What’s-your-name!”

Max looked up. “Sorry, me?”

“Yes, you. Look under the bonnet, will you?”

“But I don’t know anything about …” The driver’s door clunked closed. “This is ridiculous,” Max grumbled as he slid sideways towards the front. “Maybe we should try walking. If we can get some distance up that valley road, the taxi might meet us half way. What do you think?”

Kerry didn’t respond, just hugged herself. She was increasingly troubled that time was getting on. It had to be approaching seven now, easily.

“Bloody hell,” Max groaned. “This isn’t good.”

“What?”

“The bonnet’s already open.” He lifted it and, with the aid of his phone light, peered in – at a mishmash of shattered pipes and cylinders. “Shit.” Another kind of chill ran down his back. He straightened up stiffly. “Mr Cleghorn! You need to see this!”

“What is it?” Kerry asked.

Max shook his head. “This can’t be real …”

Cleghorn opened his door again. “What the devil’s the matter now?”

“I think you’ve been sabotaged.”

Hurriedly, Cleghorn climbed out and joined Max by the open bonnet. His face registered total dismay. At which point, movement caught Kerry’s eye.

Behind the hanging polythene.

In fact, directly behind Max.

Though it wasn’t so much a shape as something shapeless. A huge, hulking something.

She screamed and pointed. Cleghorn saw it too. He froze, eyes goggling. Max spun, but already the shape had withdrawn from view. He turned back. “This damage has been done deliberately, Mr Cleghorn. Whoever it was, they broke the bonnet open to get at it ...”

But the ex-comedian wasn’t looking either at him or the ruined engine. Gaze still locked on the polythene, he was shaking violently.

“Enough … enough of this!” he stammered. “This ends.” He dug a gloved hand into the pocket of his mac, and pulled out what they both thought was a dummy revolver, some prop from one of his shows. But then he snapped open its cylinder, and they saw that its chambers were loaded with ammunition. He clicked it closed again. “It ends now!”

He turned on them so fiercely that Max backed away along the car.

“They told me you can’t offset your fate.” Cleghorn’s voice was a snarl, his eyes teary and livid, though he barely seemed to see them. “That you can’t change your destiny once it’s fixed. But you can. I showed them you can. They thought they’d been clever, imposing that thing on me. Only slowly did I realise that was the catch, but once I did, I took the damn thing down … what if I burned my own career in the process? I’m still here, aren’t I? At eighty! And I’ve got miles and miles left yet!”

Abruptly, he seemed to remember that he had company.

He frowned. “You two … I’m sorry you’ve been caught in this. I don’t know what the rules are regarding interlopers, but I fancy they’re not good. So you should go.”

“Mr Cleghorn,” Kerry said, “if there’s someone here who shouldn’t be. Some old enemy, or …”

“Go! … While you can.”

And with gun levelled, he fought his way through the hanging sheet.

“My God …” Kerry shook her head. “Oh my God!”

Max blundered out onto the drive. “We need to exit stage left … right now.”

“But there’s clearly someone here who means Cleghorn harm. Someone he may have annoyed on the past …”

“Kerry, we need to go.” He lurched across the drive.

She hurried after him, grabbing his arm. “And go where?”

“Like I say, up the road.”

“Shouldn’t we call the police?”

“How? The front door’s locked and I’m not sure I want to go around the back, are you?”

“Max, I know he’s an old sod … but do we really want to leave him?”

“Christ’s sake, Kerry, he’s got a gun. He’s better protected than we are.”

“And what if he does something terrible with that gun?”

“All the better we’re not here.”

“Max!”

But they were now blundering up the garden, the deluge of flakes swirling, the wind factor adding a sword’s edge, a combination that almost overwhelmed their senses. Then, from somewhere behind came a muffled but sharp detonation. They stopped and turned. The house was already concealed from view; not just by the snow, but by darkness, for there were no exterior lights.

“Was that a gunshot?” Kerry said.

“I don’t know,” Max replied. “Could’ve been something blowing about in the wind.”

Another noise followed. Again dulled by the blizzard, it nevertheless was hollow and metallic, the sound a car’s bodywork might make if something struck it. “Okay, that’s it!” Max took Kerry’s elbow, steering her forward.

Still half-blinded, they went by pure instinct, tripping and tottering, only for the tall gate to loom up in front of them like a phantom. Max tried to pull it open, but yanked his hand back, yowling. Kerry activated her own phone light.

Their eyes almost popped.

The gate had not just been closed, but was fastened in place by long strands of barbed wire woven through its bars and around the gateposts. Without doubt, it was the same wire they’d seen wrapped around the shed, though such was the gnawing cold that the import of this took an age to sink in. When it did, Kerry and Mac twirled round together.

They saw only gusting, depthless flakes. But both were instinctively certain that someone was approaching. Or in Max’s mind, something.

He pushed Kerry towards the side of the garden.

“What are we doing?” she whimpered.

“There was a break in the perimeter … I saw it when we entered.” In seconds they’d come to a tall boundary wall clustered with ivy, though both brick and leaf were already pasted with snow. “Somewhere round here …”

Kerry glanced over her shoulder again. “Max, for God’s sake, find it!”

“Here!” he shouted.

And indeed, there was a crevice in the wall, as if a huge wedge of aged brickwork had fallen out. They clambered through into flat woodland. The tree trunks were sparsely spread, but there were thickets of undergrowth too, all shrouded in white. No discernible path led through, but they battled forward anyway, lashed by frozen vegetation. Kerry glanced back continually; the break in the wall fell steadily behind until that too was invisible.

“Max, where are we going?”

“We must be following the valley road,” he replied. “The river ran parallel to it, and that’s somewhere on our right. As long as we stay between the two, we’re going the right way.”

From somewhere to their rear came a loud fibrous crackle, as if a sapling had been uprooted or a hefty branch torn down. Kerry threw another backward glance, and some ten yards to their rear, saw twigs threshing violently.

“Max!” she half-screamed.

He grabbed her hand and lugged her on. Even in their panic, they realised they should try to veer leftward at some point, to connect with the road again. But the further they progressed, the more steeply the ground to their left rose upward. That had been the way of it, of course. All the way along Hockton Mill Lane, they’d descended ever deeper into this valley.

With a splintering crack, another bough behind was demolished.

Closer this time. Much closer.

They were both out of condition, but fear can drive the human body like a motor, and they crashed on and on, breath billowing. When open ground at last appeared in front, they hadn’t the time to feel relieved, but scrambled on across it for what seemed like an age, until with chests aching and lungs wheezing, they decelerated through utter exhaustion and risked a further glance behind. Nothing obvious was in pursuit.

Too fatigued to talk, they pressed on, though there was no going left now for the ground on that side had ascended to cliff-like proportions. There had to be a stair of some sort, they reasoned: a path with switchbacks maybe, old stone steps, an access road connecting to one of the derelict factories they’d seen. But they spotted nothing like that, and when they came to the first of those factories, it was no more than a shell, upright sections of jagged, rotted brickwork, heavily shelved along their tops with snow. The corrugated metal fence encircling it had collapsed, allowing them access. But they halted before going in, again scanning the woodland behind. Still nothing visible followed. Equally reassuring, the storm was finally weakening, the wind abating, fewer and fewer flakes descending.

They proceeded amid the gutted relics of buildings, the black holes of broken doors and windows gaping on all sides. As the clouds overhead cleared, the lying snow reflected spectral blue moonlight. Kerry glanced over her shoulder again. “What happened back there?”

“Dunno.” Max’s teeth juddered together as the sweat-damp in his clothes turned frigid. “All we need to think about now is getting somewhere warm.”

“Look!” She pointed between two roofless outbuildings, where a snow-covered track led away at an angle but clearly crossed over the river. “That bridge must lead somewhere.”

They lumbered forward, initial brief concerns that the bridge might be unsafe diminishing as they crossed. On the other side, an access road, presumably once having serviced the factory, appeared to ascend out of the valley. They followed it eagerly.

For about two-hundred yards.

At which point it was blocked off by a tall, steel fence.

They stood in disbelief, the body-heat steaming off them.

Max fidgeted with his phone, desperately trying to obtain a signal. While he did that, Kerry peeped along a path beaten through the snow-clad hawthorns on their right. It was certainly well-trodden and, from what she could see, mostly level. She called Max and they ventured along it. It was firm enough underfoot despite the carpet of white. The main problem was that it headed back the way they had come. When Kerry raised a concern about this, Max replied that at least they were on the other side of the river.

However, the further they followed the new route, the less comfortable they felt. Overhead, the valley side steepened until it became obvious the path was not going to suddenly divert uphill. Instead, it rolled on and on in the same direction, and all the while the excruciating cold reduced their feet to leaden weights, their hands to bloodless lumps.

“This is a nightmare,” Kerry moaned, unable to fathom how they’d finished up in such a predicament.

“Wait, look!” Max shouted.

Not far ahead, down and to the right, they saw Christmas lights.

“Surely that’s where we came from?” she said.

“There were no decorations at Cleghorn’s house, remember?”

That was true, she realised.

Max started forward, hauling her with him. “There must be another house on this side of the river. With luck, they’ll have a phone. Maybe even a car they can give us a ride in. We might make that last train yet.”

His enthusiasm infected her and they dashed forward together.

When the path commenced its descent, it was shallow, so there was no danger of slipping. They ran faster, eager to get back to some kind of sanity. Back on river-level, the route changed direction, cutting hard to the right, scything through snow-deep undergrowth. Any unease Kerry felt was allayed by knowledge that the river still lay in front of them, but then their feet started drumming on snow-covered boards, and they realised they were crossing back over via a footbridge. On the far bank, the path ended at a broken-down gateway.

Beyond this stood a mass of rhododendron bushes, and on the other side of those, the familiar outline of a garden shed. When they sidled around to the front of it, its door hung from a splintered jamb. Wearily, they turned. The house beyond the weeds was unquestionably Cleghorn’s, though now it glimmered with festive lights, bulbs in every window. A further source of light was its open back door.

“I really don’t want to go in there,” Max mumbled.

“I know,” Kerry said, “but we’re literally refrigerating out here.”

“He doesn’t do Christmas anymore. He told us that. Something’s still wrong.”

She pondered bleakly. “Suppose we sneak in, grab the phone, call 999? I don’t see we’ve any choice. We’d never make it back to that ruined factory, let alone the main road.”

She wasn’t exaggerating, and Max knew it. Their extremities felt frost-bitten.

Stealthily as possible, they proceeded, sliding sideways through the brittle structures of the weeds. At the back door, they waited again and listened. For maybe a whole minute, but the silence in the house was sepulchral. They glanced at each other, nodded, and went in. As with the shed, they immediately noticed that the back door, which, thanks to Kerry, had been held only by a single bolt at the top, had also succumbed to brute force.

More distracting than this, though, was the state of the kitchen, because a set of old, dingy fairy lights had been draped haphazardly around it. Over its cabinets, across its worktops. It was the same further in: in the warren of dim-lit passages, more strands of coloured bulbs, most thick with dust, hung from the odd nail or were slung across the tops of doors.

Creeped out beyond belief, they halted at each junction to listen. Still there was no sign that anyone else was present.

When they reached the part-open door to the lounge, they listened again. Very intently.

As before, nothing.

Holding his breath, Max pushed the door.

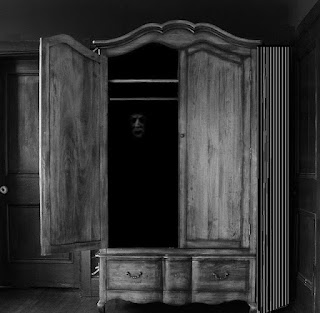

Beyond it, the spacious room stood motionless, the rancid Christmas jumper lying where Max had dropped it, the shaggy brown beanbag sitting next to the couch. The obvious main difference was that this room too had now been decked for the season. There were lights along the mantelpiece and over the tops of the curtains, while tinsel glittered from the bookcase. There was even a Christmas tree in the far corner, a scattering of white beads around the base of it to create the illusion of indoor snow. The tree itself was a scruffy, garish thing, reddish in colour, but overly decked with tinsel and crêpe, festooned with baubles, streamers and additional loops of twinkling lights.

They barely looked at it. On seeing the room was unoccupied, Max made straight for the telephone, Kerry standing guard by the door.

“Damn it!” he hissed. “The bloody line’s dead.”

“For God’s sake, it was working earlier!”

“I know, but there’s been a blizzard since then, hasn’t there!”

He slammed the receiver on the cradle three times, but it remained lifeless.

Hastily, he groped along the cable to see if it had come loose from the wall.

With nothing stirring in the corridor, Kerry crossed the room to the window with the open curtain. The lights in the building painted lurid patterns on the snow outside, but nothing else moved.

“Max, I think there’s no one …” Any additional words ended in a stupefied croak.

But it was only after Max discovered the end of the telephone cable, which had not been detached from the wall, but appeared to have been chewed clean through, that he straightened up, ice-cold again, and then saw his other half rigid as a plank, one mittened fist jammed into her mouth as she stared from close range at the Christmas tree.

Which on more prolonged inspection wasn’t a Christmas tree at all.

Near the top of it, through gaps in the festive wrappings, the tortured remnants of a human face were visible. The head had angled backward at a ninety degree angle, the mouth gaping around an upwardly protruding pole, which was either an old clothes prop, or maybe just a broken broom handle, though either way the limp form of a man had been impaled on it lengthways and then hefted upright.

Max and Kerry stood stiff. Aghast. Frozen to the core.

Unable to look any longer, Kerry averted her gaze to the floor and the scattering of fake snow. The white beads. Which, even through her swirl of horrified thoughts, were clearly not actually intended to be fake snow, but were more likely the innards of some item of furniture, the outer skin of which, all brown and furry, now lay torn in ribbons just to her left. Even then, she was too sickened with horror to make sense of this, or to notice as the great shaggy shape of the beanbag, so ingrained with dirt after all these years that it had now transformed from polar-white to deepest coffee-brown, uncurled itself and rose inexorably to its full seven feet of height.

They sensed it rather than saw it, and despite that it was almost too late.

Shrieking, they managed to dash past it, reaching the lounge doorway. Only to find that the door had been backheeled closed, and that two colourful costumes hung there: the slinky uniform of a saucy French maid, and the jester-like garb of the Lord of Misrule.

The brief halt this brought them too was all the delay the vast shape behind them needed, as it came on apace, its eyes flipping from brightest blue to searing red.

***

He did. He’s recreated every part of it.

Even when he came to take Kerry for their routine. Violet-eyed or not, he brought his burlap sack.

Course, I don’t know what time he’ll be coming to take me. I don’t even know what time it is now, because all I can see through this grimy window with the barbed wire stretched across it is darkness and falling snow. But I assume that Christmas Day is almost over. In which case, I’m not sure where I’ll fit in. Boxing Day? New Year’s Day? Most likely it’ll be Twelfth Night, the last night of the twelve days of Christmas. I’m the Lord of Misrule after all, always the last man standing. By the way, calling me ‘Lord’ is a misnomer. Look how I’m dressed. The Lord of Misrule is actually a clown. The lowest in the pecking order. Especially now. As Bernie used to say, there’s only one clown on this stage … and it isn’t me.

“But what’s this nonsense?”, I hear you cry. “What are you jabbering about? Clearly, Kerry was right. Cleghorn was a nasty piece of work, a crackpot. He’d been antagonising people for years. Someone had simply come for payback, plucking at the heartstrings of his past to drive him even crazier than he already was.”

I thought that too, which is why, as I tried to flee that lounge, I saw the old fool’s revolver on the armrest of the sofa. That’s why I grabbed it and cocked it, and punched all five remaining rounds through the centre of that great shaggy barrel chest.

But there’s the rub, you see. Because even I hadn’t bargained for what came out of it.

Can you guess? Of course you can.

Stuffing.

****

(The image of the stone ruins in the snow-bound forest is a fragment of the masterly painting, Snowy Ruins, by Markus Luotero. Meanwhile, whoever owns the bear image, or any of the images used on here, feel free to give me a shout, and I will happily give you a credit).

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

AFTER SUNDOWN

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

AFTER SUNDOWN

edited by Mark Morris (2020)

For quite a while now, British horror writer, editor and all-round expert, Mark Morris, has been looking for a new base from which to launch an all-new horror anthology series. Something unthemed but clearly inspired by the great anthology series of the past, the Pans and Fontanas, though perhaps with more modern sensibilities and a wider-ranging remit when it comes to the subgenres of horror. There have been a couple of false starts on the way, but now at last, the great man seems to have found a publishing house who are doing this worthy ambition proud.

Flame Tree Press are an imprint of London and New York-based indie publishers, Flame Tree Publishing, and though relatively new (they’ve only been trading since 2018), have already got on board the horror anthology express with Morris, to publish this first in what it is hoped will become an ongoing series of terror-filled collections of short stories.

For quite a while now, British horror writer, editor and all-round expert, Mark Morris, has been looking for a new base from which to launch an all-new horror anthology series. Something unthemed but clearly inspired by the great anthology series of the past, the Pans and Fontanas, though perhaps with more modern sensibilities and a wider-ranging remit when it comes to the subgenres of horror. There have been a couple of false starts on the way, but now at last, the great man seems to have found a publishing house who are doing this worthy ambition proud.

Flame Tree Press are an imprint of London and New York-based indie publishers, Flame Tree Publishing, and though relatively new (they’ve only been trading since 2018), have already got on board the horror anthology express with Morris, to publish this first in what it is hoped will become an ongoing series of terror-filled collections of short stories.

First of all, rather than simply hit you with a succession of brief short story outlines, I’ll let the publishers give you their own official blurb:

This new anthology celebrates the horror genre with twenty original stories from some of the top names in the field. Chosen by esteemed horror editor Mark Morris, sixteen of the tales were commissioned and four were selected from hundreds of stories sent during an open submission window. Varying in theme and subject matter, you’ll find everything from dark mysticism to killer plants, with some terrifying revenants along the way. There are even some stories so strange that they defy categorisation.

The most obvious thing to say about After Sundown is that it contains a wealth of talent from the world of dark fiction, boasting a most impressive line-up of contributors, a host of big names sitting alongside a smaller group who perhaps are lesser known, though all provide tiptop spooky material.

First off, and this is something I was delighted to see, After Sundown offers us a huge bunch of what I consider to be traditional, near-Gothic horror stories, tales that wouldn’t be out of place in an anthology from the golden age of eerie fiction, though again I reiterate that they are also very modern in tone.

Laura Purcell’s Creeping Ivy, for example, concerns a gold-digging young husband in Victorian England, who marries a wealthy widow, only to learn that she cares more about her plants than him. Likewise, Angela Slatter’s Same Time Next Year follows a forlorn female phantom, who, every year on the same night, relives the events of her own murder.

In We All Come Home by Simon Bestwick, a depressed man returns to the drear stretch of woodland where his friends disappeared when they were young, desperate to find out what happened to them. He was there, but has blotted it all from his memory, and yet he can’t help thinking that it had something to do with their all going underground.

Equally alarming but equally ‘golden age’ in tone is Bokeh by Thana Niveau, in which a single mother is concerned that her daughter, who has struggled to cope since her father ran away, has made friends with a bunch of invisible beings in her back garden whom she is convinced are fairies.

Mark Morris also opts to throw us a few tales that we might also think of as traditional in that they are grim parables of vengeance from beyond, though perhaps in these cases with a harder, darker edge than is usual; in that regard, they wouldn’t be out of place in Tales from the Crypt or one of the old Amicus portmanteaux.

This new anthology celebrates the horror genre with twenty original stories from some of the top names in the field. Chosen by esteemed horror editor Mark Morris, sixteen of the tales were commissioned and four were selected from hundreds of stories sent during an open submission window. Varying in theme and subject matter, you’ll find everything from dark mysticism to killer plants, with some terrifying revenants along the way. There are even some stories so strange that they defy categorisation.

The most obvious thing to say about After Sundown is that it contains a wealth of talent from the world of dark fiction, boasting a most impressive line-up of contributors, a host of big names sitting alongside a smaller group who perhaps are lesser known, though all provide tiptop spooky material.

First off, and this is something I was delighted to see, After Sundown offers us a huge bunch of what I consider to be traditional, near-Gothic horror stories, tales that wouldn’t be out of place in an anthology from the golden age of eerie fiction, though again I reiterate that they are also very modern in tone.

Laura Purcell’s Creeping Ivy, for example, concerns a gold-digging young husband in Victorian England, who marries a wealthy widow, only to learn that she cares more about her plants than him. Likewise, Angela Slatter’s Same Time Next Year follows a forlorn female phantom, who, every year on the same night, relives the events of her own murder.

In We All Come Home by Simon Bestwick, a depressed man returns to the drear stretch of woodland where his friends disappeared when they were young, desperate to find out what happened to them. He was there, but has blotted it all from his memory, and yet he can’t help thinking that it had something to do with their all going underground.

Equally alarming but equally ‘golden age’ in tone is Bokeh by Thana Niveau, in which a single mother is concerned that her daughter, who has struggled to cope since her father ran away, has made friends with a bunch of invisible beings in her back garden whom she is convinced are fairies.

Mark Morris also opts to throw us a few tales that we might also think of as traditional in that they are grim parables of vengeance from beyond, though perhaps in these cases with a harder, darker edge than is usual; in that regard, they wouldn’t be out of place in Tales from the Crypt or one of the old Amicus portmanteaux.

A good example is That’s the Spirit from the ever reliable Sarah Lotz. In this excellent tale, a charlatan medium struggles to convince his sick and ageing partner that he doesn’t have an actual gift, but then, one day, what may be a genuine message comes through to him. Similar paths are taken by Grady Hendrix’s Murder Board and Elana Gomel’s Mine Seven, though these are particularly strong contributions to the book in my view, so more detail about those two later.

Of course, scaring folks is one laudable aim of a book like this, but no modern horror anthology would be complete without it straying a little bit into the realms of the strange and weird as well.

Completely fulfilling that requirement here, but nevertheless disturbingly eerie, we have The Importance of Oral Hygiene from one of the genre’s true masters of unclassifiable darkness, Robert Shearman. In this astonishingly discomforting tale, a respectable Victorian lady embarks on an affair with her attractive but decidedly strange dentist, while at the same time wondering what became of his wife.

Even stranger is Catriona Ward’s A Hotel in Germany, which sees a spoiled and pretentious movie star and her PA pitch up in a hotel in Germany, where the staff are driven slowly mad by a series of absurd and sinister demands.

Swanskin, by Alison Littlewood, also falls into this category, though it overlaps into dark fantasy as well. It follows the fortunes of a young fisherman who lives in a remote community where the women can shapeshift into swans, though their menfolk feel challenged by this and are determined to take action.

Perhaps the strangest story in the entire book is The Naughty Step by Stephen Volk despite its deceptively prosaic urban setting, but it’s also one of the best, so more about this one later too.

One thing I found particularly interesting about After Sundown was the way so many of the stories have been consciously written on a small canvas. This is very much in keeping with the horror story custom – they are so often very personal experiences for their protagonists. But a couple of the stories in After Sundown take the ‘personal’ to a whole new level, giving us introspective tales set in the insular, everyday world of modern suburbanites, which only appears to be mundane.

Two particular masters of the modern horror story, Tim Lebbon and Ramsey Campbell, excel in this department.

The former contributes Research, in which a thriller writer is lured to a basement by the insane couple next door, who trap him there, eager to see what happens when he can’t release his inner darkness onto the written page. The latter gives us Wherever You Look, a tremendous piece which introduces us to another writer, though this one is haunted by a mysterious and menacing being, who initially appears to him in one of his own books.

In The Mirror House, meanwhile, by Jonathan Robbins Leon, we meet Stephanie, who is married to a the bombastic Edgar and though she finds him tolerable, feels that the relationship is ending, until she locates a hidden door, which leads to a drab mirror-image version of their own home.

Perhaps the most curiously personal of all the stories in After Sundown, one which clearly relates to heartfelt experience, comes from old-stager Michael Marshall Smith, who hits us with It Doesn’t Feel Right, in which a self-employed everyman has endless trouble getting his difficult five-year-old ready for school, though even when he notices that other kids in the neighbourhood are misbehaving in similar ways and worse, it still doesn’t occur to him that these might be down to more than mere temperament.

At the opposite end of the scale, a more explosive form of horror fiction can be found in forecasts of the apocalypse. Truly, no anthology of fantastic fiction in the 21st century can be considered complete without at least one mission to the End of the World.

There are several in After Sundown, though all differ from each other widely, each one inventive and disturbing. CJ Tudor leads the way with Butterfly Island, in which, with Earth on the cusp of Armageddon through germ warfare, a bunch of survivors head to an Australian offshore wildlife sanctuary, though there are dangers there too, not least a flock of man-eating butterflies.

A very different tone is struck by Michael Bailey’s Gave, wherein an unspecified pandemic is rapidly depopulating the planet, and one particular citizen, an ageing man who never fathered any children, becomes so obsessed with trying to protect his fellow men that he donates gallons of his own blood. But how much can he afford to give, and will there be anyone left to receive it?

More epic in concept yet is Rick Cross’s Last Rites for the Fourth World, which sees tired firemen fighting colossal forest fires in California and kids witnessing bizarre things while surfing off Hawaii, the world slowly ending through a series of catastrophic anti-miracles.

I haven’t mentioned every story in this book. That’s deliberate; there has to be something here for the reader to discover for his or herself. But hopefully I’ve illustrated just how astonishingly diverse the subject-matter is in this latest high quality horror antho from Mark Morris, which I can’t give a big enough recommendation to. Let’s just hope that its uptake among fans of the genre will be such that his new publishers will have no hesitation in commissioning more from him (as a quick addendum, Beyond the Veil, vol 2 in the series, is on the bookshelves at the time of this writing, which I will be reviewing on here as soon as I get hold of it). Here’s hoping for yearly volumes ad infinitum.

And now …

AFTER SUNDOWN – the movie.

Okay, no film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), and I honestly don’t know how likely it is, but as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my thoughts just in case someone with cash decides that it simply has to be on the big screen.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that unusual circumstances have arisen that require us viewers to be told four spooky stories.

Of course, scaring folks is one laudable aim of a book like this, but no modern horror anthology would be complete without it straying a little bit into the realms of the strange and weird as well.

Completely fulfilling that requirement here, but nevertheless disturbingly eerie, we have The Importance of Oral Hygiene from one of the genre’s true masters of unclassifiable darkness, Robert Shearman. In this astonishingly discomforting tale, a respectable Victorian lady embarks on an affair with her attractive but decidedly strange dentist, while at the same time wondering what became of his wife.

Even stranger is Catriona Ward’s A Hotel in Germany, which sees a spoiled and pretentious movie star and her PA pitch up in a hotel in Germany, where the staff are driven slowly mad by a series of absurd and sinister demands.

Swanskin, by Alison Littlewood, also falls into this category, though it overlaps into dark fantasy as well. It follows the fortunes of a young fisherman who lives in a remote community where the women can shapeshift into swans, though their menfolk feel challenged by this and are determined to take action.

Perhaps the strangest story in the entire book is The Naughty Step by Stephen Volk despite its deceptively prosaic urban setting, but it’s also one of the best, so more about this one later too.

One thing I found particularly interesting about After Sundown was the way so many of the stories have been consciously written on a small canvas. This is very much in keeping with the horror story custom – they are so often very personal experiences for their protagonists. But a couple of the stories in After Sundown take the ‘personal’ to a whole new level, giving us introspective tales set in the insular, everyday world of modern suburbanites, which only appears to be mundane.

Two particular masters of the modern horror story, Tim Lebbon and Ramsey Campbell, excel in this department.

The former contributes Research, in which a thriller writer is lured to a basement by the insane couple next door, who trap him there, eager to see what happens when he can’t release his inner darkness onto the written page. The latter gives us Wherever You Look, a tremendous piece which introduces us to another writer, though this one is haunted by a mysterious and menacing being, who initially appears to him in one of his own books.

In The Mirror House, meanwhile, by Jonathan Robbins Leon, we meet Stephanie, who is married to a the bombastic Edgar and though she finds him tolerable, feels that the relationship is ending, until she locates a hidden door, which leads to a drab mirror-image version of their own home.

Perhaps the most curiously personal of all the stories in After Sundown, one which clearly relates to heartfelt experience, comes from old-stager Michael Marshall Smith, who hits us with It Doesn’t Feel Right, in which a self-employed everyman has endless trouble getting his difficult five-year-old ready for school, though even when he notices that other kids in the neighbourhood are misbehaving in similar ways and worse, it still doesn’t occur to him that these might be down to more than mere temperament.

At the opposite end of the scale, a more explosive form of horror fiction can be found in forecasts of the apocalypse. Truly, no anthology of fantastic fiction in the 21st century can be considered complete without at least one mission to the End of the World.

There are several in After Sundown, though all differ from each other widely, each one inventive and disturbing. CJ Tudor leads the way with Butterfly Island, in which, with Earth on the cusp of Armageddon through germ warfare, a bunch of survivors head to an Australian offshore wildlife sanctuary, though there are dangers there too, not least a flock of man-eating butterflies.

A very different tone is struck by Michael Bailey’s Gave, wherein an unspecified pandemic is rapidly depopulating the planet, and one particular citizen, an ageing man who never fathered any children, becomes so obsessed with trying to protect his fellow men that he donates gallons of his own blood. But how much can he afford to give, and will there be anyone left to receive it?

More epic in concept yet is Rick Cross’s Last Rites for the Fourth World, which sees tired firemen fighting colossal forest fires in California and kids witnessing bizarre things while surfing off Hawaii, the world slowly ending through a series of catastrophic anti-miracles.

I haven’t mentioned every story in this book. That’s deliberate; there has to be something here for the reader to discover for his or herself. But hopefully I’ve illustrated just how astonishingly diverse the subject-matter is in this latest high quality horror antho from Mark Morris, which I can’t give a big enough recommendation to. Let’s just hope that its uptake among fans of the genre will be such that his new publishers will have no hesitation in commissioning more from him (as a quick addendum, Beyond the Veil, vol 2 in the series, is on the bookshelves at the time of this writing, which I will be reviewing on here as soon as I get hold of it). Here’s hoping for yearly volumes ad infinitum.

And now …

AFTER SUNDOWN – the movie.

Okay, no film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), and I honestly don’t know how likely it is, but as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my thoughts just in case someone with cash decides that it simply has to be on the big screen.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that unusual circumstances have arisen that require us viewers to be told four spooky stories.

It could be that the Crypt-keeper of Tales from the Crypt fame delivers them to us, along with a glut of the usual quips and appalling puns, or maybe, if you feel this one merits a less irreverent atmosphere, perhaps we should visit something similar to the Club of the Damned, as seen in the BBC’s atmospheric antho series of the 1970s, Supernatural.

Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The Naughty Step (by Stephen Volk): A Child Services worker is called to a domestic murder scene, where she must persuade a little boy who witnessed the killing to come away with her. He won’t, however. He can’t leave the so-called ‘Naughty Step’, terrified that if he does, a strange and terrible fate will befall him …

Linda – Lucy Davis

The Boy – Open to ideas, as I don’t know many of Britain’s young starlets.

Mine Seven (by Elana Gomel): An American woman of Russian descent holidays on Spitsbergen during the Arctic winter. When an unexplained blackout plunges the island into darkness and deep freeze, everyone at the hotel is imperilled, but even more so when an ancient evil awakens in a nearby derelict coal mine …

Lena – Rebecca Ferguson

Murder Board (by Grady Hendrix): An aged and embittered musician, who never makes a plan without consulting his battered old Ouija board, receives a message from beyond implying that his trophy wife intends to kill him. But not, he reasons, if he can figure out a way to strike first …

Bill – Alice Cooper

Caroline – Bellamy Young

Branch Line (by Paul Finch … sorry folks but I’m never going to miss the chance to put my own stuff on TV): An odious man recounts a chilling incident from 1973, when he and a schoolfriend made an ill-advised trip to the Branch Line, a derelict stretch of railway infamous locally for a suicide that once happened there and the weird spectre now said to haunt it …

Gates – Jared Harris