One additional thing. Seeing as we’re in short story territory today, I will also be reviewing the latest anthology from Midnight Street, Trevor Denyer’s excellent RAILROAD TALES. From that title, the subject matter probably speaks for itself, but those who know Trevor Denyer know that they won’t just be getting any ordinary antho. You’ll find said review, as usual, at the lower end of today’s post, in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

Before then, though, hope you enjoy ...

STUFFING2

Cleghorn hit one light-switch after another as they traversed a succession of tall, drab rooms, most of them unfurnished and connected by spartan passages laid with threadbare carpets. It was warmer than outside at least, though not markedly so, and there was a faint odour of mildew. One thing completely notable by its absence was the festive season.

“You don’t celebrate Christmas anymore, Mr Cleghorn?” Max asked.

“I had a bellyful of that during the ’70s,” came the curt response.

“Your Christmas shows are fondly remembered by the Great British public.”

“Then more fool the Great British public. Though I don’t blame them entirely. Not given the unadulterated shite that passes for British television today.”

Kerry groaned inwardly. If Cleghorn was one of these nostalgia buffs who firmly believed that TV was always better in the past, then he’d already found common ground with Max, and that was the last thing she wanted. Not that Cleghorn was a particularly warm or welcoming presence. Now that he’d put a few lights on, she could see him properly. As she’d already noted, he didn’t stoop or bend, or walk with an old man’s shuffle, but his age showed in his wizened hands and yellow, cracked fingernails, in his liver-spotted scalp and thin, peevish face. His eyes were rheumy and jaundiced, but seemed alert. His clothing was a suit of scruffy brown Tweed, long unpressed, and underneath that a collar and tie so grubby that it was difficult to tell what colour they were supposed to be.

In that regard, the past-its-best room he finally led them into fitted him to perfection.

Kerry presumed it was the lounge, and that it was located at the front of the house, but she could only guess that because though there were two large bay windows, both were screened off by drawn curtains laden with dust. In fact, dust was a common theme. The carpet was so thick with it that in the room’s corners it had curled upward into balls of fluff. It clad the lampshades too and clustered the overhead chandelier with web-like strands. Meanwhile, the furniture, while it wasn’t exactly tatty, was old and worn. Though it comprised one armchair, a sunken sofa, and alongside that, some kind of footrest, an overlarge beanbag or poof, covered with a rather disgusting furry brown material, it didn’t come close to filling the spacious room, but was arranged around a large hearth, which though it was black and sooty, clearly hadn’t been used in a long time. There was no television, Cleghorn’s main form of recreation appearing to reside with newspapers, magazines and periodicals, of which there were great numbers, some on the floor, some scattered on the sofa, some shoved into a rack.

“Make yourselves at home,” he said, hanging his scarf from a hook above the telephone table, the landline on top of which was so dated that it almost looked Edwardian. “I hope you’re not expecting food and drink?” “Oh … erm, no, not at all,” Max replied.

“Because I don’t do that sort of thing. I mean, you can have a drink, obviously. You want tea or coffee, it’s in the kitchen. Likewise, if you want something stronger …” He nodded towards an open drinks cabinet containing a range of bottles. “But I don’t wait on people.”

“We’re good, thanks.”

Despite her increasing revulsion for Bernie Cleghorn, Kerry couldn’t help being intrigued by him. To date, Max had held face-to-face interviews with at least fifteen individuals who’d formerly been famous. They’d ranged widely: from a Formula 1 ace who’d lost his nerve, to a TV cookery queen who’d been busted twice for drunken driving, on the last occasion having caused an accident that nearly killed someone; from a soap opera star whose domestic violence had seen three different women divorce him, to a footballer’s WAG and aspiring chat show hostess whom it transpired had once been a working prostitute. And yet in none of these cases had there been a hint of the bitterness she sensed here. Some had been indifferent because they were now living new lives; several had been pleased by the opportunity to put their side of the story. But all had seen lucrative lifestyles crash and burn in an instant, and yet none had been as brusque and uncivil as this fellow.

That said, in nearly all those other cases, they’d brought about their own misfortune, but the origins of Bernie Cleghorn’s trouble were murkier. Perhaps Max’s interest was understandable. What had happened to end the career of ITV’s ‘Lord of Misrule’?

The man himself had now poured a large brandy, but true to his word, hadn’t offered anything to his guests. Perched at the far end of the sofa, legs crossed, he appeared to have relaxed, but still watched distrustfully as Max, at the other end, checked the batteries and mic on his Dictaphone, and then laid his notebook on his lap.

Still wearing her anorak and scarf, Kerry sat on the armchair.

As usual, Max’s first few questions were what he considered to be ‘groundwork’. In other words, he was laying the base for the real conversation to come. They covered the subject’s childhood in post-war Coventry, a city of rationing, bomb damage and fatherless boys (of whom Cleghorn was one). The impromptu comedy shows he put on for the queues at corner shops. His gradual realisation that he had a gift for it: a child like him, an urchin with short pants and dirty knees, able to make impoverished and bereaved families laugh. His first few gigs on the working man’s club circuit of the late 1950s, usually as the warm-up for better-known, better-paid comedians. His breakthrough on radio in the early 1960s, thanks mainly to Tony Hancock and Hattie Jacques, from where the obvious next step was television, though then, as now, it was less an actual step and more a monumental leap.

Deciding that Max would be in his element listening to personal remembrances of old-time radio and TV, Kerry decided to take Cleghorn up on his offer and to make a brew. She got up and moved to the door.

“Those were the glory days,” Cleghorn was saying. “When I was young and energetic. But you had to be energetic back then, just to keep working ...”

Outside the room, even with the lights on, it was more difficult to find the kitchen than she’d expected. The door wasn’t closed behind her, so she could still hear their host talking, now recalling a summer season he’d done on the Central Pier at Blackpool with Ken Dodd and Frankie Howerd. Again, this would be meat and drink to Max and his podcast’s imaginary audience.

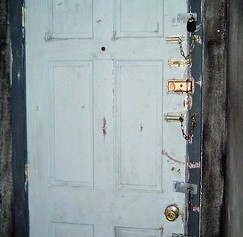

She let them get on with it, but the first corridor she took led her to the front door, which had several strong locks on it, not to mention a heap of unopened junk mail on its mat.

She headed back, passing the lounge door again.

“The amazing thing,” she heard Max say, “is that by 1968 you had Crazy House, your own TV show. For a guy in his late twenties, that was phenomenal. I mean … posh kids who’d been at Oxbridge did it. The well-connected Footlights crowd. But you had no such advantages.”

“You have to find other ways,” came the terse reply.

Kerry pressed on, turning left and coming to a junction of passages, all with darkened doorways leading off them. It bewildered her. How big was the place?

At which point she again heard a loud thud.

Another thud followed and another. Three in rapid succession.

Almost like someone demanding admittance.

Slowly, she headed in the direction she thought the sounds had come from, turning a corner and stepping through into the kitchen. Its worktops and most of its shelves were bare. Only a few basic pots and pans hung on the wall. When she spied the kettle, it was mottled with rust and, by the looks of it, non-electrical; it would be too much hassle making tea with that, she decided.

There was another thud.

Very loud.

Quite clearly from the back door.

Kerry moved towards it, curious. Did Cleghorn live alone? Did he have a partner, or a lodger? Realising that she at least had to look, she drew back the bolts at the top and bottom, turned the key in the middle, and opened the door. The first thing she noticed was that a breeze had picked up, intensifying the cold; it swept shockingly in on her and sent violent ripples through the ranks of decayed weeds in the garden.

Hands in her armpits, she stepped outside. “Hello?”

Her voice was lost in the wind. Thanks to the light from the kitchen, she could see that a few minuscule snowflakes were dancing on it.

“Hello?”

When something flapped and rustled, she spun right – and spied the polythene at the back of the car port. It was bellying fiercely.

She retreated inside, closed the door and rammed the top bolt home. She backed away, feeling strangely relieved, only for the door to bang in its frame with abrupt and savage force. It was obviously the wind, but she still jumped, and it hastened her journey back, which was a lot easier as all she needed to do this time was follow Cleghorn’s voice.

“It was getting on telly that enabled me to recruit Trudy Baker,” she heard him say, though his tone now was muffled. “Remember her?”

“How could I forget the Saucepot?” Max replied.

Kerry reached the lounge door. One of them had closed it, or the wind had.

“She was brilliant, if I’m honest.” Cleghorn again. “Funny, sexy, dead busty of course, but lots of them were back then, weren’t they?”

Kerry shook her head, wondering if those dollybird comediennes of times past might have adopted a different approach had they been given the opportunity. She opened the door and walked through, and found herself in total darkness.

“What I really want to talk to you about,” Max’s voice said, “for obvious reasons, is Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing …”

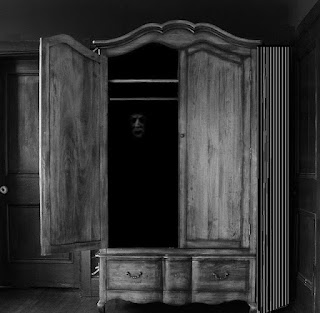

Startled, Kerry groped the wall on her left, found a switch and hit it. A dim light came on, revealing a room with bare walls and floorboards, empty except for a freestanding wardrobe.

“Where did the idea of Huckleberry Manor come from?” Max enquired.

Still puzzled, Kerry glanced around, and spotted what looked like a square glass panel in the upper corner on the left, though some time in the past it had clearly broken and been replaced with something like card or chipboard. Whatever it was, it didn’t block out sound.

At least she wasn’t going mad.

“Bing Crosby,” Cleghorn replied. “He’d been doing something similar for years with his Christmas shows.”

Kerry saw the Crosby link, she supposed, though she was now distracted by the open wardrobe door and the red and sparkly thing hanging out. The Cleghorn Christmas specials had all been broadcast from a fantasy English mansion called Huckleberry Manor, a studio set obviously, all Tudor beams and mullioned windows looking out into fake snow.

Despite herself, she ventured across the room.

Each show had lasted two hours, while a succession of celebrity guests visited, all arriving at the grand front door as prospective carol singers.

She opened the wardrobe, already suspecting what she was going to find.

It was an amazing coincidence of course, but there was no doubt what she was looking at: red and gold parti-coloured trousers and tunic, a pair of curly-toed red and gold slippers, a jester’s red coxcomb complete with golden bells. The very same jester’s costume that Cleghorn, as Lord of Misrule, had always worn for Christmas Stuffing. But it was one of two sets of clothes hanging there. She looked at the other and gave a wry smile. Not that Bing Crosby would ever have spent his festive shows deriving mucky humour from a French maid whose main contribution was her wiggly walk and ample cleavage. Because that was the second outfit: a short, black dress with white trim, and a ruffled lace bonnet.

Something else then caught her attention. She pushed the costumes apart and saw writing on the back wall of the wardrobe. At first, she was shocked. Because it was bright crimson and she wondered if it had been applied in blood. In truth it was probably too bright for that.

Even so, the letters were inscribed jaggedly, almost brutally:

She’d studied Marlowe for her A-levels, though that had been a long time ago. The only thing she remembered of his had been Dr Faustus. Not that that was the sort of classical text she’d ever associate with a performer like Bernie Cleghorn.

A burst of laughter from Max in the next room shook her out of her reverie.

It surprised her too. Their host was such an embittered presence that it had been difficult believing he could ever have been affable enough to strut his stuff as a comedian. Clearly though, he hadn’t lost the ability to be funny even now. Her gaze then fell on something that proved he had once been very funny. An object on the shelf over the empty fireplace was fluffed with dust, but still recognisable as a rose cast in gold and attached to a plaque. Kerry didn’t need to clean it off to know that it was the much-prized Rose d’Or, or Golden Rose award, which Max told her Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing had won in 1974 for one particular slapstick routine, a decorating sketch performed by Cleghorn and his pet polar bear, which, according to Variety, had “rewritten the rules of TV anarchy”.

And speaking of that …

“Buckleberry Bear soon became an essential part of Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing, didn’t he?” Max said.

“Not just the Christmas shows,” Cleghorn grunted, sounding sour again. “It was only supposed to be in the second one, but it went down so well, it ended up in all the other shows too. Even Crazy House …”

Kerry let herself out of the room, turned a couple more corners and found the open door to the lounge. As she went back in, Cleghorn, still seated at the far end of the sofa and nursing a large brandy, evidently a refill, greeted her with a strangely hostile smile.

“Welcome back, my dear. Find anything interesting in the cupboards?”

She stopped dead. “I’m sorry?”

“Any skeletons that prove everything you suspect about me? Namely, that I’m a dirty old git who deserved his fall from grace for being sexist, chauvinist, whatever other ‘ist’ you can think of?”

“I was looking for the kettle,” Kerry replied tartly. “But I’m not sure we’ve got time for tea, judging from the weather.”

“In which case we’d better get on,” Max said hurriedly.

She headed back, passing the lounge door again.

“The amazing thing,” she heard Max say, “is that by 1968 you had Crazy House, your own TV show. For a guy in his late twenties, that was phenomenal. I mean … posh kids who’d been at Oxbridge did it. The well-connected Footlights crowd. But you had no such advantages.”

“You have to find other ways,” came the terse reply.

Kerry pressed on, turning left and coming to a junction of passages, all with darkened doorways leading off them. It bewildered her. How big was the place?

At which point she again heard a loud thud.

Another thud followed and another. Three in rapid succession.

Almost like someone demanding admittance.

Slowly, she headed in the direction she thought the sounds had come from, turning a corner and stepping through into the kitchen. Its worktops and most of its shelves were bare. Only a few basic pots and pans hung on the wall. When she spied the kettle, it was mottled with rust and, by the looks of it, non-electrical; it would be too much hassle making tea with that, she decided.

There was another thud.

Very loud.

Quite clearly from the back door.

Kerry moved towards it, curious. Did Cleghorn live alone? Did he have a partner, or a lodger? Realising that she at least had to look, she drew back the bolts at the top and bottom, turned the key in the middle, and opened the door. The first thing she noticed was that a breeze had picked up, intensifying the cold; it swept shockingly in on her and sent violent ripples through the ranks of decayed weeds in the garden.

Hands in her armpits, she stepped outside. “Hello?”

Her voice was lost in the wind. Thanks to the light from the kitchen, she could see that a few minuscule snowflakes were dancing on it.

“Hello?”

When something flapped and rustled, she spun right – and spied the polythene at the back of the car port. It was bellying fiercely.

She retreated inside, closed the door and rammed the top bolt home. She backed away, feeling strangely relieved, only for the door to bang in its frame with abrupt and savage force. It was obviously the wind, but she still jumped, and it hastened her journey back, which was a lot easier as all she needed to do this time was follow Cleghorn’s voice.

“It was getting on telly that enabled me to recruit Trudy Baker,” she heard him say, though his tone now was muffled. “Remember her?”

“How could I forget the Saucepot?” Max replied.

Kerry reached the lounge door. One of them had closed it, or the wind had.

“She was brilliant, if I’m honest.” Cleghorn again. “Funny, sexy, dead busty of course, but lots of them were back then, weren’t they?”

Kerry shook her head, wondering if those dollybird comediennes of times past might have adopted a different approach had they been given the opportunity. She opened the door and walked through, and found herself in total darkness.

“What I really want to talk to you about,” Max’s voice said, “for obvious reasons, is Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing …”

Startled, Kerry groped the wall on her left, found a switch and hit it. A dim light came on, revealing a room with bare walls and floorboards, empty except for a freestanding wardrobe.

“Where did the idea of Huckleberry Manor come from?” Max enquired.

Still puzzled, Kerry glanced around, and spotted what looked like a square glass panel in the upper corner on the left, though some time in the past it had clearly broken and been replaced with something like card or chipboard. Whatever it was, it didn’t block out sound.

At least she wasn’t going mad.

“Bing Crosby,” Cleghorn replied. “He’d been doing something similar for years with his Christmas shows.”

Kerry saw the Crosby link, she supposed, though she was now distracted by the open wardrobe door and the red and sparkly thing hanging out. The Cleghorn Christmas specials had all been broadcast from a fantasy English mansion called Huckleberry Manor, a studio set obviously, all Tudor beams and mullioned windows looking out into fake snow.

Despite herself, she ventured across the room.

Each show had lasted two hours, while a succession of celebrity guests visited, all arriving at the grand front door as prospective carol singers.

She opened the wardrobe, already suspecting what she was going to find.

It was an amazing coincidence of course, but there was no doubt what she was looking at: red and gold parti-coloured trousers and tunic, a pair of curly-toed red and gold slippers, a jester’s red coxcomb complete with golden bells. The very same jester’s costume that Cleghorn, as Lord of Misrule, had always worn for Christmas Stuffing. But it was one of two sets of clothes hanging there. She looked at the other and gave a wry smile. Not that Bing Crosby would ever have spent his festive shows deriving mucky humour from a French maid whose main contribution was her wiggly walk and ample cleavage. Because that was the second outfit: a short, black dress with white trim, and a ruffled lace bonnet.

Something else then caught her attention. She pushed the costumes apart and saw writing on the back wall of the wardrobe. At first, she was shocked. Because it was bright crimson and she wondered if it had been applied in blood. In truth it was probably too bright for that.

Even so, the letters were inscribed jaggedly, almost brutally:

Fools that will laugh on earth, most weep in hell …

Christopher Marlowe *

Kerry stood bewildered. She’d studied Marlowe for her A-levels, though that had been a long time ago. The only thing she remembered of his had been Dr Faustus. Not that that was the sort of classical text she’d ever associate with a performer like Bernie Cleghorn.

A burst of laughter from Max in the next room shook her out of her reverie.

It surprised her too. Their host was such an embittered presence that it had been difficult believing he could ever have been affable enough to strut his stuff as a comedian. Clearly though, he hadn’t lost the ability to be funny even now. Her gaze then fell on something that proved he had once been very funny. An object on the shelf over the empty fireplace was fluffed with dust, but still recognisable as a rose cast in gold and attached to a plaque. Kerry didn’t need to clean it off to know that it was the much-prized Rose d’Or, or Golden Rose award, which Max told her Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing had won in 1974 for one particular slapstick routine, a decorating sketch performed by Cleghorn and his pet polar bear, which, according to Variety, had “rewritten the rules of TV anarchy”.

And speaking of that …

“Buckleberry Bear soon became an essential part of Cleghorn’s Christmas Stuffing, didn’t he?” Max said.

“Not just the Christmas shows,” Cleghorn grunted, sounding sour again. “It was only supposed to be in the second one, but it went down so well, it ended up in all the other shows too. Even Crazy House …”

Kerry let herself out of the room, turned a couple more corners and found the open door to the lounge. As she went back in, Cleghorn, still seated at the far end of the sofa and nursing a large brandy, evidently a refill, greeted her with a strangely hostile smile.

“Welcome back, my dear. Find anything interesting in the cupboards?”

She stopped dead. “I’m sorry?”

“Any skeletons that prove everything you suspect about me? Namely, that I’m a dirty old git who deserved his fall from grace for being sexist, chauvinist, whatever other ‘ist’ you can think of?”

“I was looking for the kettle,” Kerry replied tartly. “But I’m not sure we’ve got time for tea, judging from the weather.”

“In which case we’d better get on,” Max said hurriedly.

“I can always sense disapproval,” Cleghorn said to no one in particular. “It’s in the body language.”

Kerry eyed him with distaste as she sat on the armchair.

“We were talking about Buckleberry Bear,” Max said.

“Were we?” their host replied. “How unfortunate.”

“He first appeared on your show at Christmas 1971, if my notes are correct?”

“Hmm.” Cleghorn became thoughtful. “I’d done one Christmas Stuffing without him. They had me in fancy dress … the Lord of Misrule. Plus we had more celebrity guests than usual. But Granada TV felt we needed something else. Something to connect with the youngsters. I thought the same to be honest. Even though the Cleghorn show was a bit naughty, it wasn’t blue, and research had shown that kids were still watching. They were definitely watching on Christmas Day. So it seemed like a good idea.” He smiled ruefully. “And what do they say the road to hell is paved with?”

Kerry didn’t bother correcting him that it was ‘good intentions’ rather than ‘good ideas’.

“Listen!” Suddenly, Cleghorn leaned forward, his expression startlingly intense. “That bloody bear was nothing when I first acquired him! Whatever else you say in your podcast, make sure you mention that … he was nothing!”

“Erm, okay …” Max was taken aback. “I seem to recall that you first appeared with Buckleberry Bear … that wasn’t his name at the time, of course, on a television advert for a breakfast cereal.”

“Correct.” Cleghorn shook his head at the folly of his youth. “It was a big success for them. And as I say, I was looking for something extra for the show, so I acquired ownership of him full-time …” The words petered out as he glowered into the past.

“I understand that different people played him?” Max probed, to no response. “Sometimes, if there was dancing to be done, it was a dancer. Once, when you did an ice skating scene, it was a skater. Of course, their identities were always kept secret.”

“We were talking about Buckleberry Bear,” Max said.

“Were we?” their host replied. “How unfortunate.”

“He first appeared on your show at Christmas 1971, if my notes are correct?”

“Hmm.” Cleghorn became thoughtful. “I’d done one Christmas Stuffing without him. They had me in fancy dress … the Lord of Misrule. Plus we had more celebrity guests than usual. But Granada TV felt we needed something else. Something to connect with the youngsters. I thought the same to be honest. Even though the Cleghorn show was a bit naughty, it wasn’t blue, and research had shown that kids were still watching. They were definitely watching on Christmas Day. So it seemed like a good idea.” He smiled ruefully. “And what do they say the road to hell is paved with?”

Kerry didn’t bother correcting him that it was ‘good intentions’ rather than ‘good ideas’.

“Listen!” Suddenly, Cleghorn leaned forward, his expression startlingly intense. “That bloody bear was nothing when I first acquired him! Whatever else you say in your podcast, make sure you mention that … he was nothing!”

“Erm, okay …” Max was taken aback. “I seem to recall that you first appeared with Buckleberry Bear … that wasn’t his name at the time, of course, on a television advert for a breakfast cereal.”

“Correct.” Cleghorn shook his head at the folly of his youth. “It was a big success for them. And as I say, I was looking for something extra for the show, so I acquired ownership of him full-time …” The words petered out as he glowered into the past.

“I understand that different people played him?” Max probed, to no response. “Sometimes, if there was dancing to be done, it was a dancer. Once, when you did an ice skating scene, it was a skater. Of course, their identities were always kept secret.”

Cleghorn swilled more brandy, still saying nothing.

“Because of his size, though, it was mostly a burly stage-hand. Even they’d have to look out through eye-holes in the neck, I suppose. But it wasn’t always difficult for them, was it? Sometimes Buckleberry was only there to be petted by some pretty girl guest. Sometimes, he’d just be clumsy … joining you in violent routines, barroom brawls or sketches in which the set was designed to fall apart. But it usually needed to be someone big and strong. Didn’t he occasionally carry guests off in a burlap sack if they’d offended him?”

Cleghorn suppressed something that looked like a shudder.

“It was all in jest, of course,” Max said.

“You reckon?”

Even Max was unsure how to respond to that. “Buckleberry getting cross with people became a key part of the comedy, didn’t it?”

“The comedy?” Cleghorn glanced up at him. “It’s called having an ego, son.”

“An ego?”

“You remember he had glowing blue eyes?”

“Erm, yes.”

“Well … the original plan was, his eyes would be different colours to show what mood he was in. Most of the time they were blue, because he was happy. They’d flip to violet when Annette came on, because he was supposed to be in love with her. And when he got vexed, they flipped to red. Yeah … I can see you’re nodding as if you remember it. But they soon stopped turning violet, because if there was anyone he loved more than Annette, it was himself. I mean, Jesus … he was a fall-guy, a stage prop. But he didn’t understand that. Not after a while. He thought he was the sodding star.”

Kerry found herself listening in dull disbelief.

“But the main problem …” Cleghorn leaned forward again, belligerently, “is illustrated by the fact that even now, you’re clearly more interested in him than me.”

“I’m …?”

“Oh, everyone loved him. Yeah, I get that. Course they did. He was loveable. Big, cuddly polar bear. Especially on Christmas Stuffing, when he wore that daft jumper.”

“Was this …?” Max, who was rarely tongue-tied when it came to his favourite subject, was uncertain how to continue. “Do you mind me asking, Bernie, was this antipathy to Buckleberry Bear always there? Because you wouldn’t have known it. I mean, in 1975 … you and him appeared as the Broker’s Men in Cinderella in the West End. It won all kinds of awards. Twiggy was Cinders, Tommy Steele was Buttons …”

“And that doesn’t tell you anything?” Cleghorn asked.

Max couldn’t reply.

“As early as 1975, we were a double-act!” Cleghorn rubbed at his furrowed brow. “I tried to get him a solo career after that. Licensed him to do Green Cross Code commercials, attend parties in kids’ hospitals.” He shook his head. “Didn’t make any difference. In fact, it made things worse. In 1978, eight years into Stuffing’s domination of the Christmas schedules, this lavish BBC version of Alice in Wonderland was going into production. At the same time, I was one of the biggest stars on telly, especially in the so-called season of goodwill, but when I entered talks to play the Mad Hatter, I got rejected.” He arched a wispy eyebrow. “Rejected! Me! Do you know why?”

Max shrugged. “Because you were Mr ITV and it would have been incongruous?”

Cleghorn scowled. “You young cretin!” Despite his age, his voice was a whipcrack. Froth speckled his tight, grey lips. “Because there was no role in it for that sodding bear!”

A metallic clatter sounded out in the passage. Max and Kerry jumped, but their host reacted only casually, levering himself upright, placing his glass on the telephone table and leaving the room.

Kerry gave Max a long stare. “So, do we call the mental health services now, or after we get home?”

Cleghorn suppressed something that looked like a shudder.

“It was all in jest, of course,” Max said.

“You reckon?”

Even Max was unsure how to respond to that. “Buckleberry getting cross with people became a key part of the comedy, didn’t it?”

“The comedy?” Cleghorn glanced up at him. “It’s called having an ego, son.”

“An ego?”

“You remember he had glowing blue eyes?”

“Erm, yes.”

“Well … the original plan was, his eyes would be different colours to show what mood he was in. Most of the time they were blue, because he was happy. They’d flip to violet when Annette came on, because he was supposed to be in love with her. And when he got vexed, they flipped to red. Yeah … I can see you’re nodding as if you remember it. But they soon stopped turning violet, because if there was anyone he loved more than Annette, it was himself. I mean, Jesus … he was a fall-guy, a stage prop. But he didn’t understand that. Not after a while. He thought he was the sodding star.”

Kerry found herself listening in dull disbelief.

“But the main problem …” Cleghorn leaned forward again, belligerently, “is illustrated by the fact that even now, you’re clearly more interested in him than me.”

“I’m …?”

“Oh, everyone loved him. Yeah, I get that. Course they did. He was loveable. Big, cuddly polar bear. Especially on Christmas Stuffing, when he wore that daft jumper.”

“Was this …?” Max, who was rarely tongue-tied when it came to his favourite subject, was uncertain how to continue. “Do you mind me asking, Bernie, was this antipathy to Buckleberry Bear always there? Because you wouldn’t have known it. I mean, in 1975 … you and him appeared as the Broker’s Men in Cinderella in the West End. It won all kinds of awards. Twiggy was Cinders, Tommy Steele was Buttons …”

“And that doesn’t tell you anything?” Cleghorn asked.

Max couldn’t reply.

“As early as 1975, we were a double-act!” Cleghorn rubbed at his furrowed brow. “I tried to get him a solo career after that. Licensed him to do Green Cross Code commercials, attend parties in kids’ hospitals.” He shook his head. “Didn’t make any difference. In fact, it made things worse. In 1978, eight years into Stuffing’s domination of the Christmas schedules, this lavish BBC version of Alice in Wonderland was going into production. At the same time, I was one of the biggest stars on telly, especially in the so-called season of goodwill, but when I entered talks to play the Mad Hatter, I got rejected.” He arched a wispy eyebrow. “Rejected! Me! Do you know why?”

Max shrugged. “Because you were Mr ITV and it would have been incongruous?”

Cleghorn scowled. “You young cretin!” Despite his age, his voice was a whipcrack. Froth speckled his tight, grey lips. “Because there was no role in it for that sodding bear!”

A metallic clatter sounded out in the passage. Max and Kerry jumped, but their host reacted only casually, levering himself upright, placing his glass on the telephone table and leaving the room.

Kerry gave Max a long stare. “So, do we call the mental health services now, or after we get home?”

*

Hope you’re enjoyed STUFFING so far. If so, a quick reminder that PART THREE will appear right here on December 23. If you are having a good time with this material, perhaps you’ll be interested to know that, to date, I’ve published two collections of festive-themed horror stories in paperback, Audible and on Kindle. They are: IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER and THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVE. It’s probably also worth mentioning that my Victorian-era Christmas ghost story / romance, SPARROWHAWK, was shortlisted for the British Fantasy Award in the capacity of Best Novella in 2010, and that can still be acquired too.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

RAILROAD TALES

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

RAILROAD TALES

edited by Trevor Denyer (2021)

The latest anthology from British independent press powerhouse, Midnight Street, a small publishing company that has been around for quite some time now and tends to focus on contemporary horror, often with an everyday setting but invariably with strange and unsettling realities lurking just beneath the surface.

In Railroad Tales, which is surely something of a companion piece to the last Midnight Street antho, Roads Less Travelled, editor and Midnight Street owner, Trevor Denyer, takes railway lines, railway travel and railway folklore as his overarching themes, asks questions of his readers such as have they ever travelled on an empty train at night, or stood alone on a eerie platform wondering if their connection is ever going to come in, and generally (and very successfully) evokes the whole spooky culture of our railway networks: the isolated stations, the windswept junctions, the abandoned signal boxes, the level crossings where catastrophes have occurred.

The latest anthology from British independent press powerhouse, Midnight Street, a small publishing company that has been around for quite some time now and tends to focus on contemporary horror, often with an everyday setting but invariably with strange and unsettling realities lurking just beneath the surface.

In Railroad Tales, which is surely something of a companion piece to the last Midnight Street antho, Roads Less Travelled, editor and Midnight Street owner, Trevor Denyer, takes railway lines, railway travel and railway folklore as his overarching themes, asks questions of his readers such as have they ever travelled on an empty train at night, or stood alone on a eerie platform wondering if their connection is ever going to come in, and generally (and very successfully) evokes the whole spooky culture of our railway networks: the isolated stations, the windswept junctions, the abandoned signal boxes, the level crossings where catastrophes have occurred.

Railroad Tales contains 23 stories in that vein, most of them supplied by relatively new or unknown authors, but all of them serving the Midnight Street ethos by creating an eclectic range of subject-matter (though that all important detail that it must be eerie and disturbing is never neglected).

To start with, as you’d probably expect, there is more than a handful of traditional ghostly tales in this collection. Most fans of supernatural fiction will probably be well aware how often railway lines and railway workers have featured in genuinely chilling stories, and not just in the distant past such as with Charles Dickens’ The Signal-Man (1866) or Perceval Landon’s Railhead (1908). Modern master of the genre, Ramsey Campbell, contributed to the canon in 1973 with his nightmarish The Companion, and many others have done the same since.

Continuing this tradition of hitting us with something genuinely and unambiguously frightening, Railroad Tales gives us, among other stories, The Hoosac Tunnel Legacy by Norm Vigeant, in which a rickety old cargo train breaks down in a New England mountain tunnel on a little-used track in the dead of winter, the two-man crew, one of them an addict, having no choice but to solve the problem on their own … only to then find that they aren’t alone in the icy darkness.

Similarly scarifying is Caboose by Andrew Hook. In this one, a businesswoman acquires an old railway carriage, intent on turning it into a modern diner. However, at this early stage, she knows nothing about the Edwardian-era passengers who perished inside it due to a disastrous fire.

Then we have The Pier Station by George Jacobs, which takes us to a quiet seaside village where, though the railway no longer runs here, a curious young antiquarian finds an old conductor’s badge and is then haunted nightly by a mysterious ghost train.

Ballyshannon Junction by Jim Mountfield, meanwhile, is an out-and-out ghost story though with serious undercurrents, which could easily make an episode in a spooky British TV anthology (were such programmes ever made these days). It’s one of the best in the book, though, so I’ll leave the synopsis for this until a little later on.

It’s the same thing with The Number Nine by James E Coplin. This might be the best story in the entire book, at least for me. This one would make a movie, never mind an episode of TV. Again, it’s such a treat that I’ll leave its outline until a little later on.

From the in-yer-face ghostly now to stories of a more introspective, perhaps slightly deeper ilk, because Railroad Tales has got several of these too.

The first one to mention has got to be Sparrow’s Flight by Nancy Brewka-Clark, which is set in London several years after the events of Oliver Twist have ended. In this unusual tale, Oliver, now a man of business, is convinced that he sees Nancy’s ghost at a busy London railway station. He follows her onto a train, only to discover that it it isn’t some run-of-the-mill rail service.

Meanwhile, in the sad and thought-provoking tale, The Anniversary, by David Penn, a widow is drawn back by an inexplicable vision to the exact spot on the station platform where her worn-out husband killed himself, while another quite affecting story is Harberry Close by CM Saunders, though I’ll talk a little more about that one later too.

To start with, as you’d probably expect, there is more than a handful of traditional ghostly tales in this collection. Most fans of supernatural fiction will probably be well aware how often railway lines and railway workers have featured in genuinely chilling stories, and not just in the distant past such as with Charles Dickens’ The Signal-Man (1866) or Perceval Landon’s Railhead (1908). Modern master of the genre, Ramsey Campbell, contributed to the canon in 1973 with his nightmarish The Companion, and many others have done the same since.

Continuing this tradition of hitting us with something genuinely and unambiguously frightening, Railroad Tales gives us, among other stories, The Hoosac Tunnel Legacy by Norm Vigeant, in which a rickety old cargo train breaks down in a New England mountain tunnel on a little-used track in the dead of winter, the two-man crew, one of them an addict, having no choice but to solve the problem on their own … only to then find that they aren’t alone in the icy darkness.

Similarly scarifying is Caboose by Andrew Hook. In this one, a businesswoman acquires an old railway carriage, intent on turning it into a modern diner. However, at this early stage, she knows nothing about the Edwardian-era passengers who perished inside it due to a disastrous fire.

Then we have The Pier Station by George Jacobs, which takes us to a quiet seaside village where, though the railway no longer runs here, a curious young antiquarian finds an old conductor’s badge and is then haunted nightly by a mysterious ghost train.

Ballyshannon Junction by Jim Mountfield, meanwhile, is an out-and-out ghost story though with serious undercurrents, which could easily make an episode in a spooky British TV anthology (were such programmes ever made these days). It’s one of the best in the book, though, so I’ll leave the synopsis for this until a little later on.

It’s the same thing with The Number Nine by James E Coplin. This might be the best story in the entire book, at least for me. This one would make a movie, never mind an episode of TV. Again, it’s such a treat that I’ll leave its outline until a little later on.

From the in-yer-face ghostly now to stories of a more introspective, perhaps slightly deeper ilk, because Railroad Tales has got several of these too.

The first one to mention has got to be Sparrow’s Flight by Nancy Brewka-Clark, which is set in London several years after the events of Oliver Twist have ended. In this unusual tale, Oliver, now a man of business, is convinced that he sees Nancy’s ghost at a busy London railway station. He follows her onto a train, only to discover that it it isn’t some run-of-the-mill rail service.

Meanwhile, in the sad and thought-provoking tale, The Anniversary, by David Penn, a widow is drawn back by an inexplicable vision to the exact spot on the station platform where her worn-out husband killed himself, while another quite affecting story is Harberry Close by CM Saunders, though I’ll talk a little more about that one later too.

Of course, whatever its basic schematic, no horror anthology would be doing its job if it didn’t hit us with at least a few dollops of psychological terror. And Railroad Tales doesn’t disappoint on that front either.

In Where the Train Stops by Susan York, a disturbed woman undergoes a series of psychiatric regressions, a train journey into her past, to get to the root of her night terrors, and uncovers a ghastly experience.

Equally mysterious, and another strong contender for best story in the book, in The Samovar by AJ Lewis, a man tortured by his past agrees to deliver an important package from Moscow to Vladivostok, but finds the journey lonely and difficult, especially as the demons pursuing him are never far behind.

Though perhaps the most overtly psychological tale in this volume is provided by Gary Couzens with Short Platform. In this one, a drunken secretary is marooned overnight at an unmanned railway station. Exhausted and lonely, she regresses back through her unhappy life.

From the scary uncertainties of psychological horror, it’s probably not too much of a leap to the world of the strange and surreal, and Railroad Tales offers several particularly good examples of this.

First up, we have Across the Vale by Catherine Pugh, which is set in an alternative Britain, where two women ride an armoured train north to Edinburgh. To get there, however, they must first cross the dreaded ‘Vale’.

Then we have Steven Pirie’s Not All Trains Crash, in which we turn this entire subgenre on its head by meeting the ghosts created during a frightful multi-fatality railway accident, and feel their fear and pain as they are forced to move on when their decayed relic of a line is finally torn up.

Lastly in this particular category, we have an effective monster story in The Tracks, by Michael Gore, though once again I’m not going to elaborate on this one at this stage, as I want to talk a bit more about it later on.

There are other stories in this collection, of course, but those you’ll need to experience for yourself. Suffice to say that all the tales in this book stand up for themselves and make a significant impact on the reader. Midnight Street have done it again, producing a very neat and contemporary horror anthology, featuring a host of interesting voices and adding a whole glut of chilling new fiction to the ‘scary railway’ pantheon.

And now …

RAILROAD TALES – the movie.

Thus far, no film or TV producer has optioned this book yet (not as I’m aware), and in the current horror-free zone of British TV at least, it seems unlikely. But you never know. And hell, as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my thoughts just in case someone with loads of cash decides that it simply has to be on the screen.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances that require them to relate spooky stories. It could easily be something along the lines of Dr Terrors House of Horrors, a group of passengers cooped up together in a distinctly suburban train, but finding themselves travelling endlessly through a terrifying night, or perhaps they’re all marooned in one of those soulless middle-of-nowhere waiting rooms as their connections fail to arrive and the winter mists come down outside, as in The Ghost Train. The choice is, as always, yours.

But without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The Number Nine (by James E Coplin): A free-riding hobo is menaced on a night-time freight train by the ghost of a guard once famous for his use of homicidal violence …

The Hobo – Zach Gilford

Henry Hart – Dave Bautista

Harberry Close (by CM Saunders): A tired office-worker catches the wrong train and is ferried out to a strangely deserted railway station, where he immediately notices signs of brutal violence…

Tim – Timothee Chalamet

The Tracks (by Michael Gore): An outcast girl, ugly and overweight, gets an opportunity to avenge herself on her tormentors when she learns that a weird monster, the product of a curse, lives near a remote railway line and dines on rail-kill …

Clarice – Jada Harris

Ballyshannon Junction (by Jim Mountfield): In Ulster of the 1980s, a peripheral IRA figure turns informer for a local police chief, and then flees a posse of vengeful gunmen. Frightened and conscience-stricken, he arrives at derelict Ballyshannon Junction, where the many ghosts he encounters seem strangely familiar…

Marty – Ruairi O’Connor

In Where the Train Stops by Susan York, a disturbed woman undergoes a series of psychiatric regressions, a train journey into her past, to get to the root of her night terrors, and uncovers a ghastly experience.

Equally mysterious, and another strong contender for best story in the book, in The Samovar by AJ Lewis, a man tortured by his past agrees to deliver an important package from Moscow to Vladivostok, but finds the journey lonely and difficult, especially as the demons pursuing him are never far behind.

Though perhaps the most overtly psychological tale in this volume is provided by Gary Couzens with Short Platform. In this one, a drunken secretary is marooned overnight at an unmanned railway station. Exhausted and lonely, she regresses back through her unhappy life.

From the scary uncertainties of psychological horror, it’s probably not too much of a leap to the world of the strange and surreal, and Railroad Tales offers several particularly good examples of this.

First up, we have Across the Vale by Catherine Pugh, which is set in an alternative Britain, where two women ride an armoured train north to Edinburgh. To get there, however, they must first cross the dreaded ‘Vale’.

Then we have Steven Pirie’s Not All Trains Crash, in which we turn this entire subgenre on its head by meeting the ghosts created during a frightful multi-fatality railway accident, and feel their fear and pain as they are forced to move on when their decayed relic of a line is finally torn up.

Lastly in this particular category, we have an effective monster story in The Tracks, by Michael Gore, though once again I’m not going to elaborate on this one at this stage, as I want to talk a bit more about it later on.

There are other stories in this collection, of course, but those you’ll need to experience for yourself. Suffice to say that all the tales in this book stand up for themselves and make a significant impact on the reader. Midnight Street have done it again, producing a very neat and contemporary horror anthology, featuring a host of interesting voices and adding a whole glut of chilling new fiction to the ‘scary railway’ pantheon.

And now …

RAILROAD TALES – the movie.

Thus far, no film or TV producer has optioned this book yet (not as I’m aware), and in the current horror-free zone of British TV at least, it seems unlikely. But you never know. And hell, as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my thoughts just in case someone with loads of cash decides that it simply has to be on the screen.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances that require them to relate spooky stories. It could easily be something along the lines of Dr Terrors House of Horrors, a group of passengers cooped up together in a distinctly suburban train, but finding themselves travelling endlessly through a terrifying night, or perhaps they’re all marooned in one of those soulless middle-of-nowhere waiting rooms as their connections fail to arrive and the winter mists come down outside, as in The Ghost Train. The choice is, as always, yours.

But without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The Number Nine (by James E Coplin): A free-riding hobo is menaced on a night-time freight train by the ghost of a guard once famous for his use of homicidal violence …

The Hobo – Zach Gilford

Henry Hart – Dave Bautista

Harberry Close (by CM Saunders): A tired office-worker catches the wrong train and is ferried out to a strangely deserted railway station, where he immediately notices signs of brutal violence…

Tim – Timothee Chalamet

The Tracks (by Michael Gore): An outcast girl, ugly and overweight, gets an opportunity to avenge herself on her tormentors when she learns that a weird monster, the product of a curse, lives near a remote railway line and dines on rail-kill …

Clarice – Jada Harris

Ballyshannon Junction (by Jim Mountfield): In Ulster of the 1980s, a peripheral IRA figure turns informer for a local police chief, and then flees a posse of vengeful gunmen. Frightened and conscience-stricken, he arrives at derelict Ballyshannon Junction, where the many ghosts he encounters seem strangely familiar…

Marty – Ruairi O’Connor

Sounds like shivery fun! And I'd love to see that movie!

ReplyDeleteThere's no shortage of amazing movie material out there. Somehow, they keep on missing it.

ReplyDelete