If I could unveil the jacket for my next stand-alone thriller, NEVER SEEN AGAIN, and go to town a little more on the synopsis, believe me, I would. Likewise, if I could show you the cover and the amazing table of contents for the next TERROR TALES volume, or talk about the next HECK novel, or the proposed LUCY CLAYBURN TV series, or if I could say anything at all about the new screenplay I’ve just been commissioned to write after one of my older novellas was very unexpectedly optioned for film development last month, I would eagerly do so.

I would go to town, trust me. I would trumpet it from the rooftops.

But in all these cases things are not quite ready yet, and even here at du Cote de Chez Finch, we must patiently await developments. Therefore, this is another of what I consider to be my ‘holding pattern’ blogposts. In other words, I blabber a bit and chuck out a few radical ideas that some writers, readers and general followers of dark fiction might find interesting.

Therefore, I’ll this week be looking at some of the Most Extreme Cities on Earth, grim metropolises that literally scream to be written about in crime, thriller or horror fiction, urban locations that for various reasons would make absolutely perfect backdrops for dark, strange and stressful reading.

On that same theme, today’s Thrillers, Chillers book review will focus on Ahmed Saadawi’s remarkable postmodernist nightmare of present day Iraq, FRANKENSTEIN IN BAGHDAD.

If you’ve only called in for the Saadawi review, that’s absolutely fine. You’ll find it, as always, at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Zoom on down there straight away.

On the other hand, if you’ve got a minute to spare, you might find time to enjoy …

Neither thriller fiction, crime fiction, horror fiction, nor dark fiction in general, is any stranger to inaccessible and hostile locations. In fact, it’s often enhanced by them. My last blogpost, which I made at the end of last month, focussed on far-flung places, the extreme ends of the Earth (and beyond), where some of the greatest and most chilling novels ever written have been set. For the most part, though, these were wilderness environments noteworthy for their terrifyingly low or high temperatures, their dangerous flora and fauna, their challenging geography, their utter isolation from everyday human contact, and so on.

This week I thought why not take a similar idea into the city, because there are lots of inhabited places on Earth – real places! – which, while not necessarily horrendous to live in (I’m sure many of their occupants are rightly happy with their lot), would drop the jaw of the average outsider, and could make highly atmospheric backgrounds against which to set suspenseful, frightening fiction.

The ten cities I’ve picked today may already feature in novels or movies. If they do, apologies … I was unaware of the fact (which is not unusual, to be fair), but even if they don’t that doesn’t mean there haven’t been some great works of fiction set in some of the world’s most extreme urban locations.

For example, Julianne Pachico’s The Anthill is a literary but very frightening ghost story set in the heart of Medellin, Columbia, once known as the most dangerous city in the world due to the power and ruthlessness of the infamous Medellin Cartel.

Of course, cities don’t have to be deprived, or overrun by crime and squalor, or flattened by war, or impossibly isolated, or simply forgotten in order to play host to serial killers, satanic cults, organised crime, human slavery, torture-for-hire, Snuf pornography, etc. But just imagine that your fictional detective is investigating something along these lines at the same time as having to cope with everyday life (and crime) in any one of these …

The tragedies of Mexico’s border cities are widely known, but Tijuana embodies them. There are good things here, but bad things too, including Friendship Park, where locals can approach the wire fence and hold sad conversations through it with relatives who were successful in their efforts to enter the US. Much local industry comprises foreign-owned industrial plants where sweatshop conditions prevail and pay is poor. Many Tijuana neighbourhoods are thus slums, tin-shack housing balanced precariously on piles of tyres. And then there is the crime. The border outpost long attracted rough trade, meaning that sex shows and drugs were always available. But the dope wars have left the city battle-scarred, kidnappings and robberies happen regularly, and everyday tourism has collapsed. This sadly eroded statue, erected in 1990 to look to the future, says much.

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

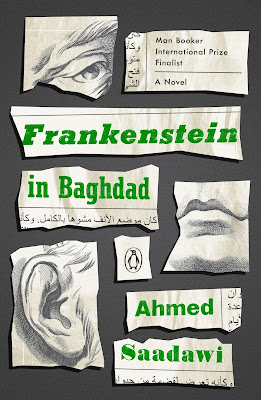

FRANKENSTEIN IN BAGHDAD

by Ahmed Saadawi (2013)

Outline

Iraq, 2003. A shell of a country in every sense of the word, but nowhere does that apply more visibly than in Baghdad itself, where the social and architectural fabric of the city has been near-enough destroyed even though the war is still raging. Saddam and his forces have gone, while the Americans and their allies have retreated into fortified enclaves, from which they only occasionally emerge in armoured columns, making swift and futile patrols. But now a range of replacement killers, not just the Sunni and Shiite militias and the Iraqi National Guard, but armed gangs of seemingly every persuasion, shoot it out daily on the shell-ravaged streets, and bombings are a common occurrence, the resulting indiscriminate explosions killing dozens each time and annihilating more and more of the city’s infrastructure, doing so much damage that what remains of the Iraqi government are completely unable to repair it.

The ordinary citizens eke out an appalling existence amid corpses and bullet-scarred ruins, and yet somehow they survive. One of these, an eccentric, happy-go-lucky junk dealer called Hadi, prowls the rubble looking for things to sell, and occasionally entertains his neighbours in the time-honoured tradition of Scheherazade with his tall stories.

Hadi, we realise, like so many of his fellow Iraqis, is in a state of ongoing traumatic stress, so much so that he barely knows it anymore. His grasp of reality is so tenuous that one day, instead of collecting rubbish and trying to sell it in his shop, he collects disparate human body parts, thinking that if he can stitch them all together and give them a proper burial, it will soothe a great number of aggrieved souls.

At the same time, in a particularly effective, near hallucinatory sequence, Hasib Mohamed Jaafar, a conscientious security guard, is killed in yet another suicide truck-bomb attack, his body almost vapourised in the blast, his spirit cast to the four winds.

Though it doesn’t remain there.

Deeply affronted by its own murder, Hasib’s spirit comes in search of a new host, and discovers the sewn-together travesty in Hadi’s outhouse. It duly possesses the homemade corpse, bringing it to a monstrous kind of life.

The patchwork horror has no initial purpose other than to wander the devastation of its former home city, though of course it can’t do this by daytime, for it is so hideous to look upon. Instead, it travels by night … and starts to commit murders.

These are not carried out for their own sake, for the hybrid thing, utterly deranged, is a mix of personalities, and having heard the prayers of those slain from whom it is comprised, now seeks vengeance on all their behalf. There is thus a rhyme and reason behind its crimewave, though few initially notice this thanks to the surplus of criminal violence already in progress. Nevertheless, urban legends spread that a monster, the Whatsitsname, as they call it, is on a non-stop nocturnal rampage, and soon the population are as terrorised by this as they are by any of the insurgent militia.

No one can locate the Whatsitsname during daytime because it has found a place to lie low. Elishva, an Assyrian Christian widow, who lives in the district of Bataween at the very heart of the guerrilla war being waged in the city, has long been in mourning for a son who never came home from the Iran/Iraq conflict of the early 1980s. When the Whatsitsname breaks into her house, the disturbed woman confronts it, and immediately decides that this is her disfigured son, returned at last.

Her home and the motherly care she provides prove convenient for the Whatsitsname, which is far from done in its quest for vengeance. It has now expanded its search, hunting down anyone it considers to be a criminal, though its righteousness is increasingly compromised because as the body parts it seeks vengeance for rot and fall away, it replaces them with new chunks of humanity, and some of these, inevitably, come from slaughtered men who were once criminals themselves.

Meanwhile, determined to investigate the ongoing bloodbath are two very different characters.

Mahmoud al-Sawadi is a local journalist who is working on the story, though his life is complicated by his Machievellian editor, Ali Bahir al-Saidi, whose mistress, Nawal al-Wadir, Mahmoud happens to be in love with, and whose intrigues look increasingly likely to get the magazine closed. Mahmoud’s direct opposite in terms of temperament and intellect is Brigadier Sorour Mohamed Majid, head of the Tracking and Pursuit Department, and a brutal, autocratic man drawn from the old regime but now charged with finding the Whatsitsname. Denuded of all his old methods, his spies and informers, Majid relies increasingly – and this is another nod, I suspect, to the magical days of The Arabian Nights and The Thief of Baghdad – on astrologers, soothsayers and other mystics, who attempt to collect intelligence by contacting the djinn.

Meanwhile, our main antagonist continues to scour the benighted backstreets, killling with a free hand, and at the same time, amassing a band of fanatical followers, creating, in effect, yet another insurgent group with which to torment the tragic city …

Review

It’s perhaps an obvious point to make that Frankenstein in Baghdad was published in English in 2018, 200 years to the year after the first publication of Frankenstein (or, as it was alternatively titled, The Modern Prometheus), but that is largely it in terms of similarities. Though both novels share a murderous, sewn-together monstrosity as their central antagonist, in the latter book there is no real concept of good v evil, minimal debate between science and religion, and no musing at all on the folly of Man playing God. In any case, Frankenstein in Baghdad was first published in Arabic in 2013, so it was never intended to be an anniversary reboot.

In truth, it’s a whole different animal from the original but it’s also a hugely affecting read, and no surprise to me that Iraqi author, Ahmed Saadawi, won the prestigious International Prize for Arabic Fiction (an Arab-speaking world version of our own Booker Prize, for which it was also later shortlisted).

On its first publication here, Frankenstein in Baghdad was rightly marketed as a horror novel. It contains so much death and brutality that it couldn’t really be anything else, apart from an anti-war novel, which it also is, but ultimately it’s much more than either or both of those things.

Throughout his intense narrative, Ahmed Saadawi muses movingly on the nature of his home country, and not just as the hellhole it became during the violence-stricken years immediately following the Allied invasion, but as a relatively new country in the midst of an ancient land, on its hugely diverse and cosmopolitan citizenship (the multipart creature referring to itself as ‘the first true Iraqi citizen’), and on how problematic all this appears to have become in modern times in the absence of effective leadership.

It’s all portrayed through the metaphor of the meaningfully-titled Whatsitsname, a composite creature progressively more at war with itself than those around it, the outcome of which confusion is a blood-trail that goes on and on, seemingly without end.

However, Ahmed Saadawi isn’t talking completely in riddles and parables. He also gives us a very stark account of life in a teeming city defeated in war and crushed by its enemies, and where the worst kind of lawless anarchy is an ongoing reality. Much of this darkness is lightened by sardonic humour, though it’s a poignant tale too, perhaps the saddest aspect of which is Saadawi’s eyewitness testimony to the resilience of his own people, who have had no option but to adapt their daily lives to a world where bombers and gunmen are running amok, to a cityscape that’s been physically devastated, to blocked roads and endless half-demolished houses, and to a government once famous for its ruthlessness but now more notable for near-comical ineptitude.

He paints a vivid but what we must also assume is an accurate picture of a broken society in which hope lies in short supply. The western powers who overthrew Saddam are nothing more by this time than omnipotent, uninterested figures who have no real stake in the country they destroyed, and yet Frankenstein in Baghdad, while a hard-hitting satire, is not a polemic or even politically slanted (it’s curious but maybe telling that among the many and varied individuals the Whatsitsname seeks to punish, there are no members of the Allied military, even though they are still present in the city). Much like the journalist version of himself, who briefly appears in the novel later on, Saadawi seems to be more interested in reporting the plain facts than offering colourful opinions. Even his monster occupies a strange twilight place between good and evil, the author simply describing the things it does and why it believes it does them (even though the creature itself is a confused mess by the end), along with the myths that are soon woven around it: a reflection perhaps of many societies’ inability to face the results of their own failings as seen in their creation of imaginary evil-doers.

It’s also a tale well-told. Originally written in Arabic, this translation of Frankenstein in Baghdad was provided by Jonathan Wright, and while it doesn’t comprise mercurial prose, it is solidly and enjoyably readable, packing in great descriptive work and much clarity of time, place and character.

As a non-Arabic speaker, I can never know what kind of impact the original text would have had on me, but I concur with the general opinion that this must be a superb rendition simply because it’s so damn good. Despite being sold as a horror novel, it was clearly never intended to be just that, and in that regard the translation’s tone is pitch-perfect, the horrors of war balanced nicely with Saadawi’s waspish humour (the monster frustrated at having to continually replace its decaying constituent parts, Brigadier Majid’s cruel but amateurish security service, who all look exactly the same as each other, and so on). And again – and I mention this again because I enjoyed it so much – we are repeatedly but subtly reminded about Iraq’s long tradition of mystery and legend, journalist Mahmoud al-Sawadi creating his own One Thousand and One Nights in the form of a scrapbook he is putting together containing his country’s strangest stories, Majid surrounding himself by buffoonish mystics and fake magicians.

I strongly recommend Frankenstein in Baghdad to fans of all literary disciplines. It’s a detailed study of present-day Iraq as well as a rattling good thriller. It’s also the Middle East as you’ll never have seen it before, and that can only be a good thing.

And now, as usual, I’m going to try and cast this saga in the event that it gets made into a film or TV series. It’s only a bit of fun of course (not least because my knowledge of Middle Eastern actors and actresses is not exactly encyclopaedic), but the authors always seem to like this part of the review, so I’m doing it anyway.

Mahmoud al-Sawadi – Malek Rahbani

Elishva – Nour Bitar

Hasib Mohamed Jaafar / the Whatsitsname – Oded Fehr

Brigadier Sorour Mohamed Majid – Hamzah Saman

Hadi – Omid Djalili

Ali Bahir al-Saidi – Anouar H. Smaine

Nawal al-Wadir – Sandra Saad