In the meantime, though, on the subject of thrillers, chillers and other writings of that ilk, I’ll be posting another detailed review, and this week it’s the turn of KIN by Kealan Patrick Burke.

As usual, if you’re only here for the book review, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Feel free to jump straight down there and check it out. Before then, though, let’s roll back the centuries to …

Darker Ages

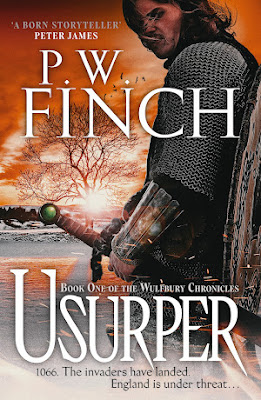

I’m guessing that most people reading this column will be familiar with my recent diversion from the world of crime and thrillers into the land of historical adventure fiction, as initially seen in my book of last April, USURPER, which told a blood and thunder tale set during the Norman invasion of England.

It wasn’t a total diversion, by the way; there’ll be more crime-thriller news from the Côté de Chez Finch in the next few weeks.

USURPER seems to have done pretty well. It got some good reviews and garnered some very pleasing

thumbs-ups from a range of respected authors …

An action-packed, coming-of-age, adventure set against the upheaval and battles of 1066 … Matthew Harffy

Fearsome battles, believable characters, uncommon valour. A relentless page turner … David Gilman

An authentically blood-soaked historical epic to rank with the best … Anthony Riches

With all the brutal power of a battle-axe to the head, Finch brings 1066 to life in new and vivid ways … Steven A McKay

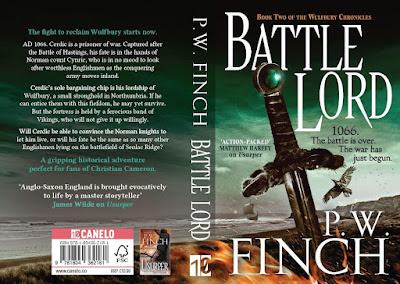

Well, as mentioned, next January, the second volume in the Wulfbury saga, BATTLE LORD, will hit the bookshelves, though it’s available for pre-order right now of course. Here’s a quick thumbnail outline:

It’s October 1066. The battle of Hastings is over, and King Harold and the flower of his English army lie slaughtered. But the Normans have suffered too, and from this point on, can only advance with caution. Though this doesn’t stop them harrying the English people: burning, raping and pillaging.

The prisoners they have taken are equally mistreated. One of these is Cerdic Aelfricsson, second son and sole surviving heir to the earldom of Ripon, whose extensive holding in the north of England is centred around the hill fortress of Wulfbury.

Wulfbury is the only reason Cerdic is alive. He has teased his captors with information that this earldom and all its treasures can now be theirs, though he makes no bones about the fact that they must first steal it back from Wulfgar Ragnarsson, a Viking warlord whose private army splintered away from Harald the Hardraada’s invasion force and captured it for themselves.

The household of the Norman count, Cynric of Tancarville, is the particular group in whose chains Cerdic resides. Not trusting their duke to give them their due reward, they are strongly tempted to march north, but they know that will be through enemy territory, while the Viking opponent awaiting them grows stronger every day.

Before then of course, they still have duties to discharge for their duke, namely the capture of the Saxon fort at Dover, and England’s religious capital, Canterbury, then the hardest nut of all to crack, London. Only then of course, can the duke genuinely claim the crown of England.

All through this ordeal of chaos and war, Cerdic can only use his wits to survive. At the same time, though, he becomes increasingly close to a fellow hostage, Yvette d’Heimois, the English-speaking daughter of a Norman count currently living in exile, and two Norman knights, Turold and Roland, the former whose mother was English, the second whose adherence to the code of chivalry leads him to show compassion to the prisoners.

That said, the benign presence of Yvette, Turold and Roland is counterbalanced for Cerdic by several ferocious adversaries: Joubert, Count Cynric’s cruel and uncontrollable son, Yvo ‘the Slayer’ de Taillebois, his personal attack-dog, and Duke William himself, an implacable tyrant, who hasn’t yet earned his epithet ‘Conqueror’, but is currently known for all sorts of reasons as ‘the Bastard’.

If you like the sound of BATTLE LORD, as I’ve already said, you can pre-order it right now. Or, if you need further persuasion, check out a few reviews and see what you think on it on its day of publication, January 8, next year.

It’s my sad duty to report that my Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers column, which I’ve been running on this blog since 2015, and in which I think I’ve now reviewed several hundred books, will shortly be finishing.

I should say straight away that airing my thoughts publicly and extensively on those works by other authors that I have particularly enjoyed has been one of the great joys of my life in recent years. But, for various reasons now, I need to bring this to a close.

Most people who are familiar with this blog will probably recognise that I offer very detailed reviews of these novels, anthologies and story collections. Some might say I actually go into too much detail, and that writing hundreds and hundreds of words each time is an OTT response and maybe too much for the average internet browser to bother reading.

In truth, I suspect this latter may be the case.

Many’s the time sadly when I’ve had only a very limited response to these reviews, which is a huge amount of time wasted. Don’t get me wrong … I’ve not been doing this so that people will discuss my book reviewing skills (such as they are) online, though it’s nice if an author responds, and that happens quite a lot, but ultimately it’s an exercise in trying to spread the word about a great piece of fiction that has made an impact on me personally, and it’s too often the case that I’ve seen no evidence I’m achieving that … so, what’s the point?

Of course, what it really boils down is that, even if each of these reviews generated a waterfall of chatter, they’ve simply become too time-consuming an exercise. I have my own writing to do – two more novels are in the offing, with more to add, while I also have several short story commissions – so it’s just not possible to keep taking out two or three days twice a month to write continuous book reviews. (On top of that, it does take the enjoyment out of reading, having to make copious notes in a pad while you’re working your way through a damn good book).

I won’t be putting it to bed straight away. I’ve still got several reviews in the barrel, which I’ll post over the next couple of months, and I’ll always post a quotable paragraph on social media if I really like a book, but I suspect that 2024 will be the first year in quite some time when the Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers section of this twice-monthly blogpost is basically no more.

And now, speak of the Devil …

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

A series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

KIN by Kealan Patrick Burke (2012)

Outline

When Claire Lambert is found on the side of the road near Elkwood in rural Alabama, raped, mutilated and blinded in one eye, Jack Lowell, the black farmer who discovers her, knows immediately who’s to blame. A local hillbilly clan, the Merrills, controlled by their fearsome father, Papa-in-Gray, and their odious, deranged mother, Mamma-in-Bed, have been terrorising the district for ages. While content to leave their neighbours alone (mostly), they are always ready to waylay visitors, not just robbing, torturing and killing them, but cannibalising the remains afterwards. And by that, I mean literally cannibalising them, as in cooking and eating them, and burning what’s left-over on huge, greasy bonfires.

Claire’s small group of happy-go-lucky hitchhikers has suffered exactly this fate, but Claire herself escaped and in the process managed to kill one of her captors.

None of this, by the way, has happened ‘on camera’. We learn all about it through Claire’s dazed recollections and the few things she manages to say to her reluctant rescuer and then to a retired doctor, who patches her wounds but is hesitant to publicise the incident because both he and Lowell now know that the Merrills won’t rest. One of their victims has escaped, someone who can now implicate them in multiple homicides. Not only that, she slew one of their own.

Lowell’s dim-witted but good-natured son, Pete, drives Claire away when she’s fit to travel, and only just in time, the vengeance of the Merrill family then falling ferociously on both the farmer and the good-hearted medical man, the latter taking the blame posthumously when local lawman, Sheriff McKindry, finds fragments of Claire’s friends scattered in his cellar.

The story of the mad, murdering doctor is accepted by the state police, and Claire is despatched home to her sorrowing family in Ohio, unable to persuade anyone that it was a whole group of men who attacked them. Her older sister, Kara, won’t listen, because she hopes the terrible issue is now over. Relatives of the other victims feel much the same way. With one exception.

Thomas Finch, the brother of Claire’s deceased boyfriend, and an ex-boyfriend, himself, of Kara’s, is a veteran of the Iraq War. As such, he’s now an embittered, introspective man, whom Kara doesn’t like or trust anymore, and who seems to be constantly on the verge of doing something self-destructive. Secretly, he’s tortured by the memory of shooting an innocent Iraqi woman and her child, and later covering his back by lying that they were suicide bombers, though no one else knows about this except his old combat buddy, Beau. Finch does believe Claire that the real murderers down in Alabama have got away scot free, and seeks permission of the bereaved families to go and look for them. Most don’t want anything to do with him; they are comfortable middle-class citizens, so even though ravaged by grief, they can’t conceive of a vigilante rampage. One, however, a wealthy chap, agrees to bankroll Finch’s mission of vengeance, which allows him and Beau to buy high-power weapons.

Young Pete, meanwhile, is also ready to get payback. Despite his endless good humour, with his Pa dead and his home burned, he’s been left with nothing but the family truck. He heads north to Detroit, to try and hook up with Louise, his former stepmom, but Louise, though she’s glad to see him, is currently dealing with a wannabe gangster boyfriend and all the trouble that brings, and eventually is severely wounded just trying to prevent Pete from getting involved himself.

Pete thus drives to Ohio, to check on Claire. He really is an innocent soul. It never enters his head that she might regard him as a real-life reminder of her terrible ordeal rather than the friendly kid who helped her. But Claire, who’s been strictly forbidden by Kara from accompanying Finch and Beau back to the South, now sees Pete as a new kind of salvation. Because, the moment Kara looks the other way, he can drive her down to Alabama. And whatever revenge is going to be had on the diabolical Merrill clan, she can have a piece of it too …

Review

Back in 2012, I would have wondered how much more an author could have wrung out of the ‘hillbilly horror’ genre. Much earlier, in 2001, I attended World Horror in Seattle and heard opinions from various US writers that they felt this particular neck of the literary backwoods was now thoroughly explored.

However, Kealan Patrick Burke gives it a new lease of life in his rural thriller, Kin, though not in ways you might expect.

Yes, the terror of the malformed and the inbred is all there, the extreme sexual violence is there, the distortion of religious belief, the deep, dark woodland filled with dense, thorny undergrowth. The Southern Gothic atmosphere pervades it from the start. We are in a familiar world, and a familiarly ominous one, where local law enforcement pay lip service to their badges, doing no more for visitors than offering friendly advice that they ignore such and such a wooded back-road; where said roads inevitably lead to mysterious ramshackle farms, heaps of junked, rusted machinery, loads and loads of seemingly abandoned cars; and where hairy bad guys in dungarees are likely to leap out of the trees at any second, armed with hatchets, knives and bows.

But I say it again, Kin is what I’d call a ‘rural thriller’ rather than a traditional ‘hillbilly slasher’, Burke setting up the brutal attack on the innocent band of hikers before the novel has even started, and instead of focussing on their appalling and protracted suffering, choosing to analyse the events that follow (and inevitably spin out of control).

I’ve often wondered when watching movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Wrong Turn or The Hills Have Eyes, how the few survivors of such ordeals would ever have been able to get on with their lives afterwards. We got a hint of it in Deliverance and Wolf Creek, where, in the former, the very least they could expect were repeated sweat-soaked nightmares, and where, in the latter, there was a general disbelief that such events could ever have happened, the survivors themselves coming under suspicion of murder.

But in Kin, Kealan Patrick Burke takes it a whole lot further – and here’s the really clever bit, because when this author is talking about ‘kin’, he isn’t just talking about the cannibal clan at the heart of the horror, he’s also talking about the response their atrocious act elicits from the siblings of those slain. In fact, that’s what he’s talking about mainly. So often in this kind of tale, we meet a tightknit group of uneducated killers living in rural isolation, fearing and hating the rest of the world, and subsequently prepared to die for each other even though there is much abuse and cruelty among them. Well, newsflash! – other ordinary folk, the ‘men of the world’ as they are referred to in this book, care about each other too, and in Kin, the Merrill clan of Elkwood are about to learn that the hard way.

Even so, the author doesn’t use this as a reason to simply drag us through a gutter of depraved self-justifying violence. Fighting back against deadly criminals with equal deadly force would be a big step for any civilised person to take; not just a terrifying prospect, but a moral quandary all of its own. And this is the key aspect of Kin. If your life was genuinely ruined by an act of such horrific violence as this, and the outrage was compounded by the indifference or incompetence (or both) of local police forces – so much that you felt there was no option but to take the law into your own hands – what kind of agonies would you go through as you, firstly, sought to convince yourself that this was the only solution, and, secondly, then had to persuade sufficient others to form an effective posse?

Even in America, where there are guns aplenty, it takes the war veterans Finch and Beau, two men used to conflict and whose lives, on the whole, have already ended, to light the touchpaper. Pete only gets involved because he too has nothing left in his life: his Pa is dead, his home incinerated, his erstwhile mother, Louise, a woman with serious problems of her own. Even Claire, the most damaged character in the story, only goes back to Elkwood because she is being so smothered with care and concern (and at the same time subjected to anger and annoyance for having brought this tragedy on their family) that she knows she’ll only be able to cut loose by taking direct action of her own. And even then, they all follow hard and bumpy roads reaching these conclusions.

I’ve seen some critiques of Kin that take issue with its middle section, where the killers themselves are off the page and, instead of watching them commit more heinous deeds, we ruminate painfully with their stressed and indecisive victims. Of course, what may be boring to some, to others (to me, for instance) is the thing that marks this novel out as more of a thriller than a horror, because it means that we’re dealing with things ultra realistically, a sad, grave tone that is maintained throughout the narrative.

Kin might be a story that we’ve seen before, but rarely will we have seen it done in as grown-up fashion as this. For example, the Merrills are not simply mad, bad and dangerous to know because they come from the country. There are other country folk in here, like Jack Lowell and even Mamma-in-Gray’s brother, Jeremiah Crawl, who, while both from the boondocks, are not evil.

The Merrills are the way they are because Papa-in-Gray, their patriarch, is hopelessly insane, a paranoid religious maniac who has consciously sought segregation and raised his family with such fear and suspicion of the rest of society, treating its corruptive influence as literal poison, that it will only lead to one thing when they encounter it. (I should say that though we’re in authentic serial killer country here, our main antagonist so overwhelmed by delusion that he might as well get what he can from his fellow men because he’s completely dehumanised them in his own mind, the cannibal element feels perhaps a little unnecessary. I can’t help thinking this brings a degree of lurid sensationalism into the novel that it doesn’t really need).

The other thing that impresses me about the Merrills is that they’re not indestructible. We’re a world away from Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, who just keep coming no matter what you do to them. The Merrills are brutal bullies, but they’ve never squared up to combat vets before, and the result of that is inevitable and foreseeable. Not only that; they aren’t totally solid with each other: son Luke, for example, has developed a conscience, and Papa, though he cruelly and horribly punishes the boy, remains wary of him for the rest of the book.

On the whole, though, you almost start to feel for the Merrills in the end, mainly because their simple understanding of what they believe to be an ultra-hostile world has so failed to prepare them for reality that, at times, they are more like silly children than deadly criminals (though you don’t linger with that misconception for long). When their demise occurs, it’s deserved but inevitable, and they almost seem to feel this themselves, predicting the end of their world with a sad, fatalistic air. Papa remains in denial until the end, of course: Mama was a saint, God is still on their side, he’ll find another woman and have new sons, all will come good. It’s all so pathetically deluded. Not that he doesn’t thoroughly deserve the biblical end that awaits him in the final pages.

In terms of the other characters, Sheriff McKindry is an equally complex villain. It’s an old trope, the corrupt southern lawman who’ll go out on a limb to keep things just the way they are. In this version, he’s as much a thief and scavenger as the Merrills, but he too is finally aware that he’s got in over his head, and he genuinely regrets this, as well as the sufferings of all those others caught up in the Merrills’ web, which up until now he’s turned a blind eye to.

I was less enamoured by Finch and Beau, who, dare I say it, are a little bit stock, and like so many veterans in modern day fiction, spend a lot of time talking about how nothing seems to matter anymore, though once again they have clear, defined voices and as we’re still in the real world, neither of them, thankfully, is Rambo.

That leaves only Pete and Claire of our main cast, who, between them, are a very different pair of heroes from the norm, and each very engaging in his/her own way. Claire would normally be fetchingly pretty; she was once, but now she’s been gruesomely disfigured, and switches continually between sweetness and anger. Pete, a young black kid with learning difficulties but a cheerful outlook, lives in a tragi-comic fantasy, where just because he was in the truck that picked Claire up when she was first hurt means he’s destined to be her boyfriend. He’s no hope on this score, of course, but one of the most attractive things about him is, even when he starts to realise this, he never lets it diminish his positive outlook.

As you’ve probably realised, I enjoyed Kin immensely. It was a quick read, though very well written – almost lyrical at times. I do think there are perhaps one or two moments of introspection too many, when we lose the thread of the action because characters are thinking deep, immersive thoughts. But to other reviewers this is a good thing, even steering the book in a literary direction.

Ultimately, of course, it’s all in the eye of the beholder. I’d just say this: read Kin. It doesn’t do what it says on the tin, but for that reason I think you’ll thorough enjoy it.

As I so often, and so ill-advisedly do after reviewing books on this blog, I’m now going to attempt to cast Kin on the off chance that it gets made into a movie or TV series. So many of the books on here should get that treatment, but never seem to. But in this case, as with all others, here’s hoping. (And remember – the one good thing about this is that I have no limits on how much I can spend on my actors).

Claire – Kara Hayward

Pete – Tyrel Jackson Williams

Papa in Gray – Dennis Quaid

Luke – Josh Hutcherson

Louise – Gabrielle Union

Finch – Sean Faris

Beau – Omari Hardwick

Sheriff McKindry – Scott Glenn

With all the brutal power of a battle-axe to the head, Finch brings 1066 to life in new and vivid ways … Steven A McKay

Well, as mentioned, next January, the second volume in the Wulfbury saga, BATTLE LORD, will hit the bookshelves, though it’s available for pre-order right now of course. Here’s a quick thumbnail outline:

It’s October 1066. The battle of Hastings is over, and King Harold and the flower of his English army lie slaughtered. But the Normans have suffered too, and from this point on, can only advance with caution. Though this doesn’t stop them harrying the English people: burning, raping and pillaging.

The prisoners they have taken are equally mistreated. One of these is Cerdic Aelfricsson, second son and sole surviving heir to the earldom of Ripon, whose extensive holding in the north of England is centred around the hill fortress of Wulfbury.

Wulfbury is the only reason Cerdic is alive. He has teased his captors with information that this earldom and all its treasures can now be theirs, though he makes no bones about the fact that they must first steal it back from Wulfgar Ragnarsson, a Viking warlord whose private army splintered away from Harald the Hardraada’s invasion force and captured it for themselves.

The household of the Norman count, Cynric of Tancarville, is the particular group in whose chains Cerdic resides. Not trusting their duke to give them their due reward, they are strongly tempted to march north, but they know that will be through enemy territory, while the Viking opponent awaiting them grows stronger every day.

Before then of course, they still have duties to discharge for their duke, namely the capture of the Saxon fort at Dover, and England’s religious capital, Canterbury, then the hardest nut of all to crack, London. Only then of course, can the duke genuinely claim the crown of England.

All through this ordeal of chaos and war, Cerdic can only use his wits to survive. At the same time, though, he becomes increasingly close to a fellow hostage, Yvette d’Heimois, the English-speaking daughter of a Norman count currently living in exile, and two Norman knights, Turold and Roland, the former whose mother was English, the second whose adherence to the code of chivalry leads him to show compassion to the prisoners.

That said, the benign presence of Yvette, Turold and Roland is counterbalanced for Cerdic by several ferocious adversaries: Joubert, Count Cynric’s cruel and uncontrollable son, Yvo ‘the Slayer’ de Taillebois, his personal attack-dog, and Duke William himself, an implacable tyrant, who hasn’t yet earned his epithet ‘Conqueror’, but is currently known for all sorts of reasons as ‘the Bastard’.

If you like the sound of BATTLE LORD, as I’ve already said, you can pre-order it right now. Or, if you need further persuasion, check out a few reviews and see what you think on it on its day of publication, January 8, next year.

Thrillers, Chillers no more

It’s my sad duty to report that my Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers column, which I’ve been running on this blog since 2015, and in which I think I’ve now reviewed several hundred books, will shortly be finishing.

I should say straight away that airing my thoughts publicly and extensively on those works by other authors that I have particularly enjoyed has been one of the great joys of my life in recent years. But, for various reasons now, I need to bring this to a close.

Most people who are familiar with this blog will probably recognise that I offer very detailed reviews of these novels, anthologies and story collections. Some might say I actually go into too much detail, and that writing hundreds and hundreds of words each time is an OTT response and maybe too much for the average internet browser to bother reading.

In truth, I suspect this latter may be the case.

Many’s the time sadly when I’ve had only a very limited response to these reviews, which is a huge amount of time wasted. Don’t get me wrong … I’ve not been doing this so that people will discuss my book reviewing skills (such as they are) online, though it’s nice if an author responds, and that happens quite a lot, but ultimately it’s an exercise in trying to spread the word about a great piece of fiction that has made an impact on me personally, and it’s too often the case that I’ve seen no evidence I’m achieving that … so, what’s the point?

Of course, what it really boils down is that, even if each of these reviews generated a waterfall of chatter, they’ve simply become too time-consuming an exercise. I have my own writing to do – two more novels are in the offing, with more to add, while I also have several short story commissions – so it’s just not possible to keep taking out two or three days twice a month to write continuous book reviews. (On top of that, it does take the enjoyment out of reading, having to make copious notes in a pad while you’re working your way through a damn good book).

I won’t be putting it to bed straight away. I’ve still got several reviews in the barrel, which I’ll post over the next couple of months, and I’ll always post a quotable paragraph on social media if I really like a book, but I suspect that 2024 will be the first year in quite some time when the Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers section of this twice-monthly blogpost is basically no more.

And now, speak of the Devil …

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

A series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

KIN by Kealan Patrick Burke (2012)

Outline

When Claire Lambert is found on the side of the road near Elkwood in rural Alabama, raped, mutilated and blinded in one eye, Jack Lowell, the black farmer who discovers her, knows immediately who’s to blame. A local hillbilly clan, the Merrills, controlled by their fearsome father, Papa-in-Gray, and their odious, deranged mother, Mamma-in-Bed, have been terrorising the district for ages. While content to leave their neighbours alone (mostly), they are always ready to waylay visitors, not just robbing, torturing and killing them, but cannibalising the remains afterwards. And by that, I mean literally cannibalising them, as in cooking and eating them, and burning what’s left-over on huge, greasy bonfires.

Claire’s small group of happy-go-lucky hitchhikers has suffered exactly this fate, but Claire herself escaped and in the process managed to kill one of her captors.

None of this, by the way, has happened ‘on camera’. We learn all about it through Claire’s dazed recollections and the few things she manages to say to her reluctant rescuer and then to a retired doctor, who patches her wounds but is hesitant to publicise the incident because both he and Lowell now know that the Merrills won’t rest. One of their victims has escaped, someone who can now implicate them in multiple homicides. Not only that, she slew one of their own.

Lowell’s dim-witted but good-natured son, Pete, drives Claire away when she’s fit to travel, and only just in time, the vengeance of the Merrill family then falling ferociously on both the farmer and the good-hearted medical man, the latter taking the blame posthumously when local lawman, Sheriff McKindry, finds fragments of Claire’s friends scattered in his cellar.

The story of the mad, murdering doctor is accepted by the state police, and Claire is despatched home to her sorrowing family in Ohio, unable to persuade anyone that it was a whole group of men who attacked them. Her older sister, Kara, won’t listen, because she hopes the terrible issue is now over. Relatives of the other victims feel much the same way. With one exception.

Thomas Finch, the brother of Claire’s deceased boyfriend, and an ex-boyfriend, himself, of Kara’s, is a veteran of the Iraq War. As such, he’s now an embittered, introspective man, whom Kara doesn’t like or trust anymore, and who seems to be constantly on the verge of doing something self-destructive. Secretly, he’s tortured by the memory of shooting an innocent Iraqi woman and her child, and later covering his back by lying that they were suicide bombers, though no one else knows about this except his old combat buddy, Beau. Finch does believe Claire that the real murderers down in Alabama have got away scot free, and seeks permission of the bereaved families to go and look for them. Most don’t want anything to do with him; they are comfortable middle-class citizens, so even though ravaged by grief, they can’t conceive of a vigilante rampage. One, however, a wealthy chap, agrees to bankroll Finch’s mission of vengeance, which allows him and Beau to buy high-power weapons.

Young Pete, meanwhile, is also ready to get payback. Despite his endless good humour, with his Pa dead and his home burned, he’s been left with nothing but the family truck. He heads north to Detroit, to try and hook up with Louise, his former stepmom, but Louise, though she’s glad to see him, is currently dealing with a wannabe gangster boyfriend and all the trouble that brings, and eventually is severely wounded just trying to prevent Pete from getting involved himself.

Pete thus drives to Ohio, to check on Claire. He really is an innocent soul. It never enters his head that she might regard him as a real-life reminder of her terrible ordeal rather than the friendly kid who helped her. But Claire, who’s been strictly forbidden by Kara from accompanying Finch and Beau back to the South, now sees Pete as a new kind of salvation. Because, the moment Kara looks the other way, he can drive her down to Alabama. And whatever revenge is going to be had on the diabolical Merrill clan, she can have a piece of it too …

Review

Back in 2012, I would have wondered how much more an author could have wrung out of the ‘hillbilly horror’ genre. Much earlier, in 2001, I attended World Horror in Seattle and heard opinions from various US writers that they felt this particular neck of the literary backwoods was now thoroughly explored.

However, Kealan Patrick Burke gives it a new lease of life in his rural thriller, Kin, though not in ways you might expect.

Yes, the terror of the malformed and the inbred is all there, the extreme sexual violence is there, the distortion of religious belief, the deep, dark woodland filled with dense, thorny undergrowth. The Southern Gothic atmosphere pervades it from the start. We are in a familiar world, and a familiarly ominous one, where local law enforcement pay lip service to their badges, doing no more for visitors than offering friendly advice that they ignore such and such a wooded back-road; where said roads inevitably lead to mysterious ramshackle farms, heaps of junked, rusted machinery, loads and loads of seemingly abandoned cars; and where hairy bad guys in dungarees are likely to leap out of the trees at any second, armed with hatchets, knives and bows.

But I say it again, Kin is what I’d call a ‘rural thriller’ rather than a traditional ‘hillbilly slasher’, Burke setting up the brutal attack on the innocent band of hikers before the novel has even started, and instead of focussing on their appalling and protracted suffering, choosing to analyse the events that follow (and inevitably spin out of control).

I’ve often wondered when watching movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Wrong Turn or The Hills Have Eyes, how the few survivors of such ordeals would ever have been able to get on with their lives afterwards. We got a hint of it in Deliverance and Wolf Creek, where, in the former, the very least they could expect were repeated sweat-soaked nightmares, and where, in the latter, there was a general disbelief that such events could ever have happened, the survivors themselves coming under suspicion of murder.

But in Kin, Kealan Patrick Burke takes it a whole lot further – and here’s the really clever bit, because when this author is talking about ‘kin’, he isn’t just talking about the cannibal clan at the heart of the horror, he’s also talking about the response their atrocious act elicits from the siblings of those slain. In fact, that’s what he’s talking about mainly. So often in this kind of tale, we meet a tightknit group of uneducated killers living in rural isolation, fearing and hating the rest of the world, and subsequently prepared to die for each other even though there is much abuse and cruelty among them. Well, newsflash! – other ordinary folk, the ‘men of the world’ as they are referred to in this book, care about each other too, and in Kin, the Merrill clan of Elkwood are about to learn that the hard way.

Even so, the author doesn’t use this as a reason to simply drag us through a gutter of depraved self-justifying violence. Fighting back against deadly criminals with equal deadly force would be a big step for any civilised person to take; not just a terrifying prospect, but a moral quandary all of its own. And this is the key aspect of Kin. If your life was genuinely ruined by an act of such horrific violence as this, and the outrage was compounded by the indifference or incompetence (or both) of local police forces – so much that you felt there was no option but to take the law into your own hands – what kind of agonies would you go through as you, firstly, sought to convince yourself that this was the only solution, and, secondly, then had to persuade sufficient others to form an effective posse?

Even in America, where there are guns aplenty, it takes the war veterans Finch and Beau, two men used to conflict and whose lives, on the whole, have already ended, to light the touchpaper. Pete only gets involved because he too has nothing left in his life: his Pa is dead, his home incinerated, his erstwhile mother, Louise, a woman with serious problems of her own. Even Claire, the most damaged character in the story, only goes back to Elkwood because she is being so smothered with care and concern (and at the same time subjected to anger and annoyance for having brought this tragedy on their family) that she knows she’ll only be able to cut loose by taking direct action of her own. And even then, they all follow hard and bumpy roads reaching these conclusions.

I’ve seen some critiques of Kin that take issue with its middle section, where the killers themselves are off the page and, instead of watching them commit more heinous deeds, we ruminate painfully with their stressed and indecisive victims. Of course, what may be boring to some, to others (to me, for instance) is the thing that marks this novel out as more of a thriller than a horror, because it means that we’re dealing with things ultra realistically, a sad, grave tone that is maintained throughout the narrative.

Kin might be a story that we’ve seen before, but rarely will we have seen it done in as grown-up fashion as this. For example, the Merrills are not simply mad, bad and dangerous to know because they come from the country. There are other country folk in here, like Jack Lowell and even Mamma-in-Gray’s brother, Jeremiah Crawl, who, while both from the boondocks, are not evil.

The Merrills are the way they are because Papa-in-Gray, their patriarch, is hopelessly insane, a paranoid religious maniac who has consciously sought segregation and raised his family with such fear and suspicion of the rest of society, treating its corruptive influence as literal poison, that it will only lead to one thing when they encounter it. (I should say that though we’re in authentic serial killer country here, our main antagonist so overwhelmed by delusion that he might as well get what he can from his fellow men because he’s completely dehumanised them in his own mind, the cannibal element feels perhaps a little unnecessary. I can’t help thinking this brings a degree of lurid sensationalism into the novel that it doesn’t really need).

The other thing that impresses me about the Merrills is that they’re not indestructible. We’re a world away from Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, who just keep coming no matter what you do to them. The Merrills are brutal bullies, but they’ve never squared up to combat vets before, and the result of that is inevitable and foreseeable. Not only that; they aren’t totally solid with each other: son Luke, for example, has developed a conscience, and Papa, though he cruelly and horribly punishes the boy, remains wary of him for the rest of the book.

On the whole, though, you almost start to feel for the Merrills in the end, mainly because their simple understanding of what they believe to be an ultra-hostile world has so failed to prepare them for reality that, at times, they are more like silly children than deadly criminals (though you don’t linger with that misconception for long). When their demise occurs, it’s deserved but inevitable, and they almost seem to feel this themselves, predicting the end of their world with a sad, fatalistic air. Papa remains in denial until the end, of course: Mama was a saint, God is still on their side, he’ll find another woman and have new sons, all will come good. It’s all so pathetically deluded. Not that he doesn’t thoroughly deserve the biblical end that awaits him in the final pages.

In terms of the other characters, Sheriff McKindry is an equally complex villain. It’s an old trope, the corrupt southern lawman who’ll go out on a limb to keep things just the way they are. In this version, he’s as much a thief and scavenger as the Merrills, but he too is finally aware that he’s got in over his head, and he genuinely regrets this, as well as the sufferings of all those others caught up in the Merrills’ web, which up until now he’s turned a blind eye to.

I was less enamoured by Finch and Beau, who, dare I say it, are a little bit stock, and like so many veterans in modern day fiction, spend a lot of time talking about how nothing seems to matter anymore, though once again they have clear, defined voices and as we’re still in the real world, neither of them, thankfully, is Rambo.

That leaves only Pete and Claire of our main cast, who, between them, are a very different pair of heroes from the norm, and each very engaging in his/her own way. Claire would normally be fetchingly pretty; she was once, but now she’s been gruesomely disfigured, and switches continually between sweetness and anger. Pete, a young black kid with learning difficulties but a cheerful outlook, lives in a tragi-comic fantasy, where just because he was in the truck that picked Claire up when she was first hurt means he’s destined to be her boyfriend. He’s no hope on this score, of course, but one of the most attractive things about him is, even when he starts to realise this, he never lets it diminish his positive outlook.

As you’ve probably realised, I enjoyed Kin immensely. It was a quick read, though very well written – almost lyrical at times. I do think there are perhaps one or two moments of introspection too many, when we lose the thread of the action because characters are thinking deep, immersive thoughts. But to other reviewers this is a good thing, even steering the book in a literary direction.

Ultimately, of course, it’s all in the eye of the beholder. I’d just say this: read Kin. It doesn’t do what it says on the tin, but for that reason I think you’ll thorough enjoy it.

As I so often, and so ill-advisedly do after reviewing books on this blog, I’m now going to attempt to cast Kin on the off chance that it gets made into a movie or TV series. So many of the books on here should get that treatment, but never seem to. But in this case, as with all others, here’s hoping. (And remember – the one good thing about this is that I have no limits on how much I can spend on my actors).

Claire – Kara Hayward

Pete – Tyrel Jackson Williams

Papa in Gray – Dennis Quaid

Luke – Josh Hutcherson

Louise – Gabrielle Union

Finch – Sean Faris

Beau – Omari Hardwick

Sheriff McKindry – Scott Glenn