Most scholars conclude that it actually dates back to the earliest days of agrarian society, when the harvest had been gathered and stored, and with the land seemingly dead and frozen, people had nothing to do for a couple of months but sit by the roundhouse fire and tell tall tales. I’ll also take a punt and say that the apparent death of Nature – for that was how it must have appeared in those primitive days – would neatly correspond with notions of dark spirits, the evil doings of elves, goblins and other mysterious woodland sprites, and the arrival of heralds from beyond, here to warn us that the deities were taking a dim view of our antics on Earth.

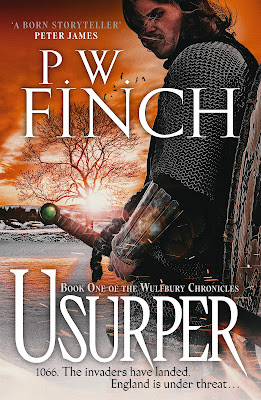

Anyway, that’s that bit done. As promised, a curtailed preamble this year (hope you appreciate that). Today, I’m going to hit you with a relatively new story of mine, WHAT DID YOU SEE?. It was first published in 2020 in the ALCHEMY PRESS BOOK OF HORRORS 2, edited by Peter Coleborn and Jan Edwards.

Here it is again, for your delectation. Hope you approve ...

WHAT DID YOU SEE?

“Excuse me,” the old woman said, leaning across the table, “I hope you ladies don’t think I’m intruding, but I couldn’t help overhearing that you’re on your way to Norwood Lee?”

Kay and Marsha were a little surprised. Not least because they’d been speaking together quietly while the old woman had apparently been asleep, but also because, while it might be impossible not to eavesdrop in the close confines of a crowed train compartment, it wasn’t the sort of thing you’d readily admit to.

As if reading their thoughts, the old woman gave an apologetic smile and raised a shrivelled, jewel-encrusted hand. “It’s just that I live close to Norwood Lee. I know it well, and…” Her words tailed off as she pondered the best way to continue.

She was in her late seventies and though wizened, with a mop of unruly white hair and far too much make-up, some degree of feminine allure remained. She’d once been a beauty, that much was evident, though as time had taken her looks, perhaps it had taken her wits also. It was warm and cosy inside the carriage, but an overlarge fur coat, a woolly hat and a many-times wrapped-around muffler engulfed the old dear in dramatic and preposterous fashion.

“Forgive me … you must think me a silly meddlesome old thing. But, and I’m sorry to ask you this … you ladies weren’t by any chance thinking about going to the parish church tonight?”

The two young women glanced at each other.

“No … erm.” Kay shrugged. “We … we don’t go to church.”

“Oh…”

“I fear we misunderstand each other. Looking to attend the Nine Lessons at Norwood Lee tonight would be futile. It’s only a hamlet really, and the church reflects this. We call it a ‘parish church’ but it’s actually rather small, with an even smaller congregation these days, I’m sad to admit. The vicar, Reverend Donaldson, has four other village churches in his care … so tonight the Christmas service will be held at St Margaret’s in Long Hanborough. But that wasn’t what I was referring to anyway.”

Kay, who, with her honey-blonde hair, schoolgirl looks and petite frame, was always the more approachable of the twosome, leaned forward. “I’m sorry,” she said in her soft Manchester accent, “but you’ve really lost us.”

“Ah, well … yes.” The old woman sighed. “That will certainly be the case shortly, I fear…”

“Hey, I hope you don’t mind,” Marsha interrupted, her puzzlement finally giving way to aggravation. “But we’re making our plans for Christmas and we’re kind of busy…”

The old woman gave her a strange strained look, as if something about this particularly concerned her. “Just so long as those plans don’t involve the Wilcote crypt, my dear.”

Marsha pulled a face. “I’m sorry?”

The woman dug under her fur, producing a pair of glasses on a chain, placed them on the end of her nose, and drew a sleeve back to glance at a delicate little watch. “We are ten minutes from Bladon, which is my stop. I may just have enough time to tell you a story…” She arched an inquisitive eyebrow. “If you’ll permit me?”

Marsha was a tall Brummie, older than Kay by two years, and much more athletic thanks to her hockey and netball. She had a shock of dark hair and attractive feline features, which made her a striking individual to look at, but she was also inclined to surliness when denied her own way. She now looked increasingly disgruntled, only a covert squeeze of the thigh from Kay, which translated into “let’s not make a scene” preventing her giving voice to this.

“It’s just that you remind me of me and my friend, Miriam,” the old woman said. “We made this exact same journey to Norwood Lee on Christmas Eve some sixty years ago…”

“I don’t think you quite understand,” Marsha replied tersely. “We’re not going to this parish church of yours. We don’t believe in God.”

That arched eyebrow again. “And yet you’re making plans for His birthday?”

Marsha looked flustered at that. “It’s a holiday, okay? We’re going to Norwood Lee for a break … to get away from it all.”

The woman sat back, her lips pressed together in a curious half-smile. Kay thought she looked sad rather than offended and couldn’t help but feel embarrassed by Marsha’s abruptness. At the same time there’d been something about the urgency with which the old dear had suddenly tried to speak to them that left her uneasy. She and her friend had come this same way sixty years ago? It would have been nice to know what the exact circumstances of that long-ago trip were that made her feel it necessary to pass on a warning.

On top of that, it could be awkward travelling for the next ten minutes in total silence, face-to-face with someone they’d just reprimanded.

“What happened sixty years ago?” Kay asked.

Marsha tensed, sucking in a tight breath.

“It can’t hurt to know,” Kay said quickly. “After all, we’re strangers in Norwood Lee. We don’t know anything about the place.”

“Whatever it is, I’ve just made it quite clear that we won’t be going near the parish church,” Marsha retorted.

“My dear, my dear…” The old woman shook her head gently as if chiding a recalcitrant child. “Norwood Lee is a speck on a map. You can’t go anywhere in the village without being close to the parish church.”

“And is there a problem with that?” Kay asked. “You mentioned a crypt. Is it dangerous?”

The woman leaned forward, gazing birdlike from one to the other. Irritably, Marsha scrunched up the plastic cellophane from the packet of sandwiches she’d eaten earlier but couldn’t throw it anywhere and so had to keep it screwed into her fist.

“The crypt houses the tomb of a knight, Sir Henry Wilcote, and his wife, the Lady Abigail,” the woman said. “It’s fifteenth century but safe enough to visit as it’s been well maintained – at least, that’s my understanding. Personally, I haven’t been down there since December 24, 1958.”

If nothing else, that impressed Kay.

The old woman remembered the exact date and had clearly crossed off all the days that had passed since. Whatever had happened, it had obviously been significant.

“The crypt is easily accessible … or it was,” the woman said. “There are two doors on the church’s south side. The one on the left leads to the vestry, but that one is kept locked when the church is closed as there are some items of value inside. But the one on the right, the old one … that leads down to the crypt. That one is not locked, or it never was in our day. No one went down there, you see. During the Wars of the Roses, Sir Henry fought for the House of Lancaster. It was a bitter struggle, and when it was over he was fortunate to return to his wife, who he was very much in love with. They remained together for the rest of their lives, but later on developed a reputation for dabbling in the dark arts.”

Marsha muttered under her breath, “For Heaven’s sake…”

“It was a dangerous time, and this, it was said, was the only thing that spared them the vengeance of Richard III.”

Kay continued to listen, intrigued despite herself.

“I’m not saying that people believed it, of course,” the woman added. “Most likely, the dark arts story was untrue, a fable that grew up in later centuries. Otherwise, how could the Wilcotes have been laid to rest on hallowed ground?”

Marsha muttered again, something about her not being able to care less. Anything relating to religion was of zero interest to her. She tried not to consciously hate it. Hating stuff was no good for you. She just considered it silly and irrelevant.

“That rumour alone created a sinister atmosphere in the crypt,” the woman said. “The effigies of the knight and his lady were badly eroded. Little more than lumpen monstrosities back in 1958, so Heaven knows what they look like now. After nightfall, no one, not even the most rational man, would wish to go down there.”

“So how come you went down?” Marsha asked. “I’m assuming that’s what you’re going to tell us? That you and this Miriam went down into the crypt that Christmas Eve.”

“Yes, it’s true.” The old woman removed her glasses, digging a tissue from her sleeve to clean the lenses. “We both lived in Oxford then. But we’d heard all about the church at Norwood Lee, and the Wilcote crypt. We were children. Grammar schoolgirls. We didn’t believe there was anything particularly ominous about the place but one particular superstition had … well, it’d rather captivated us.”

She carefully replaced her glasses. They awaited her explanation.

“It was claimed,” she finally said, “that if one visited the crypt on Christmas Eve one might perform a love divination.”

“A what?” Marsha said.

“A simple ritual.” The old woman considered. “These old country ways … they were always simple at heart. I suppose so that simple folk could practice them.”

“A love divination?” Kay said. “I don’t understand?”

“On the stroke of midnight, at the very moment of Christmas, one stood at the foot of the slab on which the knight and his lady rested, threw a handful of hemp-seeds over one’s left shoulder, and uttered these words: Hemp-seed I scatter, hemp-seed I sew, He that’s my true love, come after me and mow.” She paused briefly, looking breathless, as if mere recollection of the rhyme had taken something out of her. “The belief was that on completion of this ritual one glanced over one’s shoulder and one would see the image of one’s future spouse. Ahhh…” She registered their bemused expressions. “You look at me as if I’m mad. I can’t blame you. Even we didn’t think it would work. We scoffed at the folly of it, but it would be a lie to say that we weren’t intrigued and … maybe a little hopeful. You must understand, being the era it was, we girls were first and foremost raised to seek out solid dependable husbands…”

“And you seriously thought we were going to Norwood Lee to do this?” Marsha interrupted, almost openly scornful.

“In truth, my dear, no.” The old woman removed her glasses again, staring from the train window. “I can see, having spoken to you, that you are spirited, intelligent and independent-minded ladies, who no doubt will make marvellous futures for yourselves without the assistance of any men.”

You don’t know the half of it, Kay thought, but she kept this to herself.

The old woman now seemed embarrassed by the story she’d told. “Doubtless, you have no truck with folk tales or other such childish beliefs.”

“As I say,” Marsha said, “we’re not religious.”

But then the old woman turned again, unexpectedly, and reaching sharply across the table, seized Kay’s wrists in both her hands.

“Hey!” Marsha protested, reaching out, herself, to intervene. However, the woman released Kay almost as quickly as she’d grabbed her.

“Please understand…” The rheumy gaze roved frantically from one to the other. “I made no assumptions about your character or intellect. But when I heard you were headed for Norwood Lee, old memories were stirred. And I couldn’t … well, I couldn’t allow it. Not without warning you first.”

“Well, so far you haven’t warned us about anything,” Kay said, a little shaken. “What happened in the crypt, Mrs…?”

“Miss Jenkins. Gertrude Jenkins.”

“What happened in the crypt, Miss Jenkins?”

The woman fidgeted with her tissue, shrugging. “We performed the ritual. Obviously we did. When we actually got there it was almost midnight and terribly cold. I wasn’t so sure about it but Miriam was adamant. And very excited. Even as a youngster at school her head had been in the clouds about men and boys. From earliest girlhood she’d dreamed that somewhere a handsome beau was awaiting her. So … after we’d performed the divination, which as I say was very simple, she was the first to look over her shoulder. She was so eager, her eyes bright with candle-fire, cheeks flushed, mouth wide open…”

She paused, as though struggling to remember, or at least to understand.

All around them the swaying carriage was crowded with noisier-than-usual folk heading home, having finally finished their last day’s work before Christmas commenced. That good-natured uproar now dwindled to a dull distant monotony as Kay and Marsha waited.

“And then she screamed,” Gertrude Jenkins said in a distant voice. “Just that. Gave a short, rather terrible scream.”

“Okay,” Kay said, vaguely alarmed. “So … what did she see?”

The woman’s expression remained blank as if she’d mulled this matter over many times and had never yet found a satisfactory answer. “A wraith-like figure, apparently. Of a much older heavier-set man than she’d hoped for. A man with a sour face, and an air about of him of violence and cruelty.”

Kay’s skin prickled. “And did she go on to marry such a person?”

“I honestly don’t know.” The woman sniffled into her tissue. “I lost contact with Miriam after we left school. And in the half-year before that happened she never spoke about the incident again. Or about very much in fact. All the life seemed to have been sucked out of her, all the gaiety, the hopes, the dreams…”

“Oh, that’s ridiculous,” Marsha cut in. “Total nonsense. Your friend could have married anyone she wanted. She didn’t have to fall in with a brutish idiot just because of some stupid spell in a church cellar…”

The woman eyed her with something akin to pity. “My dear, if only it were that simple. I’m sure that, even at your tender years, the pair of you already know many a poor girl who’d never have entertained the man in her life had she known his true nature.”

“And what did you see?” Kay asked, sensing that there was more to come.

“Me, my dear?” The woman gave a wintry smile. “Why … I didn’t look. When I saw Miriam’s reaction, I couldn’t bring myself to. And I’ve never looked over my shoulder since. For any reason at all.”

“Sorry?” Marsha sounded even more sceptical. “You’ve never glanced over your shoulder once in the last sixty years?”

“I can’t afford to take the chance.”

The train decelerated as they slid into a station. There was a stirring and shuffling as passengers collected baggage and fastened coats.

“Ah … this is me,” Gertrude Jenkins said. “Bladon.”

She pulled a pair of woollen gloves over her thin beringed hands and produced two bags, a shopping bag and a handbag from the small space on the seat beside her.

The younger women watched her askance. She noted this.

“I hope I haven’t unduly frightened you?” she said.

“You’ve never once looked over your shoulder?” Kay was fascinated by the mere thought.

The train came to a standstill and there was noisy movement all along the carriage. The woman stood up, making to join the slow-moving queue forming in the aisle.

“It’s not as difficult as it may sound,” she said. “I hear him, you see. From time to time. When it’s quiet. Always close behind, just waiting for me to look.” She regarded them dully. “It’s a terrible sound. Quite horrific. I know just from that noise that I’d be appalled at what I’d behold—”

Kay couldn’t help herself. “Wait, Miss Jenkins. I mean … not looking? That keeps this thing at bay?”

“I’ve no idea, child. It has so far, but I’m only seventy-seven next February, and some would say there is still time.” With a weak smile directed at no one in particular she stepped into the aisle and edged towards the doors. “Just heed my advice, ladies. I beg you.”

Several seconds passed before either of the twosome could speak. Inevitably, it was Marsha.

“My dad always says that one advantage of rail travel being so expensive these days is that you don’t get as many loonies on trains. Wait till I tell him about this one.”

Kay stared out onto the platform, which was crowded with people heading for the exits. Gertrude Jenkins was among them, her short distinctive figure still buried in that overlarge fur coat. More by instinct than design, Kay glanced down at the old woman’s booted feet and the tracks they left in the snow, and then at the snow behind her, to see if any other tracks were appearing there. But there were too many other people and it was already churned to slush. So there was no way to tell.

Kay Letwin and Marsha Finnegan had met on the very first day of Freshers’ Week at Balliol College, Oxford, when by happy fortune they casually chatted in the Student Bar only to find that they’d both enrolled on the same course to study geography. It was well into that first year of study, during a very drunken Christmas party, when they learned that they’d come to be more to each other than mere friends. But it was almost twelve months after that before their lives and emotions had become so interwoven that they’d begun tentatively to discuss tying some kind of knot.

Initially, both were hesitant, Marsha wondering if they were getting their priorities wrong and if it would distract from their coursework and interfere with their exams; Kay suspecting that they’d allowed themselves to be seduced by the relative novelty of gay marriage and that they might be rushing into something they hadn’t thought about sufficiently. In addition, neither of their families, with the sole exception of Tom, Kay’s older brother, were aware of their daughters’ sexual orientation, and while neither bunch were especially conservative in their views it would likely come as a shock if the first they heard of it was the day they were invited to a wedding. In light of all this the two friends had taken what they considered to be the very adult decision of isolating themselves for a few days, over the next Christmas period in fact, in a relatively luxurious environment – Tom’s weekend cottage – where they would discuss every aspect of their relationship, weighing up the pros and cons and hopefully reaching the most sensible decision possible.

Even so, despite the seriousness of this – it was a weighty matter which could impinge on both their lives for decades to come – when they disembarked from the GWR train at Norwood Halt that very chilly Christmas Eve, with backpacks hoisted, scarves, gloves and hats in place, and unbroken snow crunching underfoot, it was impossible not to feel a tingle of holiday excitement.

Unlike at Bladon, where plenty of people had got off the train, Kay and Marsha were the only ones at Norwood Halt, and it was eerily beautiful. After descending the staircase alone (hanging onto each other for dear life) and passing out through the unmanned entrance hall, they found themselves on high ground overlooking the silent village.

“This is perfect,” Kay said, delighted. “Wouldn’t surprise me if a horse came clopping through, pulling a sleigh.”

“Yeah, it’s also damn cold,” Marsha replied. “Let’s get indoors, eh? See if your lovely brother’s come through for us.”

Tom Letwin, who was ten years older than Kay, was an investment banker in the City, but all their lives he’d been her closest buddy and confidante. His cottage in Norwood Lee, “a crash-pad in the sticks”, as he referred to it, was only one of several properties he owned. His pride and joy was a villa in the foothills of the Gascon Pyrenees, which he used in summer for the sun and in winter for the skiing. Kay and Marsha had been invited to join him there now with his wife, Tamara, and their two children, but when she’d said that she wanted some privacy he’d happily handed over the keys to the crash-pad.

They found it in a narrow mews just behind the post office, one of a row of three. Tom had already warned them that it was small, comprising a single room downstairs with a kitchenette, and a single bedroom upstairs. But they had a real fire, for which there was lots of firewood and kindling stored in the outhouse, and once they lit that, he’d promised that it would be very comfortable. It also boasted a plethora of olde worlde fixtures, including a large stone hearth carved with ancient characters, exposed wooden beams on both floors, and a staircase so steep that it was more like a loft-ladder ascending through a hatch.

They built up the fire until it was roaring, and when they checked in the kitchenette and the ice-box of a scullery attached to it, they found all the consumables they’d need, from six-packs of lager to boxes of wine, from packets of biscuits and cereal, bread, butter, milk, sugar and eggs, all the basics, to sacks of potatoes, carrots, onions and the like. There were also a few extras, provided generously and unexpectedly by Tom, such as an oven-ready prize turkey, several strings of sausages, a box of mince pies and a tinned Christmas pudding.

“Good as it gets,” Marsha said a couple of hours later, when they were unpacked and settled. She wriggled her sock-clad toes in front of the fire while using the remote for the big hi-def telly to channel-hop through a procession of atmospheric but for the most part empty-headed festive entertainments.

Kay muttered a vague response as she wandered – for the third time now – to the window overlooking the back garden. There wasn’t much out there. Again, it was small and blanketed with snow, but beyond the frosty hedge, wooded hills rose into view against the hanging orb of the moon. Silhouetted on its bluish lunar face, amid black tangles of leafless boughs, was the castellated tower of a country church.

“You really want to go up there, don’t you?” Marsha said, joining her.

Kay, who’d first spotted the religious edifice outside and had immediately been entranced by it, was taken aback by the question.

“No,” she said, rather too quickly. “Well … look, I know it’s silly. It’s just … I keep thinking … you know, we’re here to make a big decision. And if we go up there and perform this crazy ritual and when we look over our shoulders, we see each other … well, then we’ll know, won’t we?” She gave a sheepish shrug. “It’ll make everything a lot easier. We can relax and enjoy Christmas without any heavy conversation.”

“Are you actually serious, babes?” Marsha looked astounded. “It’s an old wife’s tale.”

“In which case it can’t hurt, can it?”

Marsha had never been relaxed with that argument: if you didn’t believe in something, where was the harm in indulging it? So often it had been used by religious types in conflict with irreligious types. “If you don’t believe in God you’ve no problem with me going to church, have you, because it doesn’t mean anything anyway?” What that point of view didn’t allow for was the fact you were still being asked to give credibility to something that simply wasn’t real, which was basically asking you to be dishonest. But then again, you also had to consider the give-and-take so essential to successful relationships, and in their particular case, the fact that Kay had long been interested in the odd, the unusual and the uncanny. She had a pile of ghost books back in her room at college, was fascinated by folklore and the occult, and even posted about stuff like that on her blog from time to time.

“I just thought it would be cool to check it out.” Kay shrugged. “Don’t you think that was an interesting story about the crypt?”

“I think it was a horrible story, and a load of guff as well, no disrespect to batty old Miss Jenkins. But … as I don’t believe it’ll do anything at all, let alone do any harm, I don’t suppose I mind a late-evening walk. Should be quite invigorating.”

Kay beamed. “And on a clear night we can see all the Christmas stars.”

“They’re the same stars as usual, Kay.”

“Don’t be boring.”

“I’ll try not to be.” However, as she sat on the sofa pulling her walking-boots back on, Marsha had a thought. “There is one thing. If you genuinely want to perform this ritual, or something similar to it – and frankly, I can’t believe we’re even contemplating such a nonsensical game – you’ve not got everything you need.”

Kay looked puzzled. “We don’t really need anything.”

“Hemp-seed,” Marsha said. “Whatever that actually is.”

“Oh, dear.” Kay looked worried. Before a sly smile crept over her face and she produced from behind her back a sack of “healthy option” granola. “Would you believe, there’s hemp-seed in this?”

Marsha tried not to laugh. “So … we’re going up that hill to chuck a handful of breakfast cereal over our shoulders and that will confirm the hopes and fears of all our years?”

Kay’s impish smile faded, as if such mockery was hurtful but perhaps not entirely unjustified. “Like you said, it’s game. We don’t have to do it. I just wanted to check out this spooky crypt at a time when it’s supposed to be at its spookiest.”

Marsha sighed obligingly. “Well, it’s not far off midnight. If we’re going, we should go now.”

They couldn’t initially find the way. There were no signs to it and no one was around to ask. But fortunately the parish church was visible from just about everywhere thanks to its lofty perch, and after circling the green a couple of times they chanced on a narrow passage between two cottages, which initially they’d thought a private entry, and this led to a road on the village outskirts. Evidently the road was used very little because only one or two pairs of runnels from passing vehicles marked the carpet of snow lying across it, but they followed it for thirty yards to a finger-posted junction, and from here another minor road lead uphill in roughly the right direction.

Breath smoking and backs bent, they trudged up the slippery incline, following a pavement that was all but indistinguishable from the road itself. To either side, thickets of frozen trees crowded against the low, stone walls.

“Getting spooky,” Marsha observed.

“Thought you didn’t believe in that stuff,” Kay said.

“I don’t. And neither do you, remember. It’s just a bit of fun.”

Some fun, Kay thought, squeezing her gloved hands into fists to prevent the fingers turning numb, grunting as she struggled to keep her footing.

A short time later, a lychgate appeared on the left. No doubt it would normally stand as an icon of elaborate rusticity, a simple latched gate hung between two wooden posts wound with rose bushes and supporting a tiled roof, the lintel of which was inscribed with Latin lettering. But now that roof was buried under snow and the lintel dangling with icicles.

“With any luck this’ll be locked, and we can go back to the cottage,” Marsha said.

But the gate wasn’t locked. They had to force it open, the hinges stiff with frost, but a sufficient gap had soon been made and they sidled quickly through, hoping to avoid precipitating an avalanche from overhead.

Beyond the lychgate a path that was just about visible meandered through the trees towards a dark distant structure. When they passed a large noticeboard on the right, it was so plastered with flakes that they couldn’t read it.

“Everyone loves a white Christmas,” Marsha said. “Until one comes along and the sheer impracticality of it kicks in … like, when you can’t even find out what time you’re supposed to go to church.”

Kay didn’t comment, her eyes fixed on the gaunt building looming ahead.

The truth was, and she’d only partially admitted this to herself, she really wasn’t sure the route they were currently contemplating was one she wanted; okay, they were both uncertain about it but her fears, she suspected, went much deeper than Marsha’s. She’d never had any partner before coming to university, girl or boy. Oh, there’d been the usual kissing and fumbling at school parties, but none of that had carried an emotional price-tag. In contrast, it had been very different with Marsha. Kay had been strongly attracted to the older student from the moment she’d met her, and now felt deeply connected to her. If there was such a thing as spiritual love then perhaps this was how Kay felt. But increasingly she had reservations. Marsha was taller and sturdier than she was, which gave her a protective aura. Kay couldn’t help wondering if she’d fallen for someone like this because she’d been unconsciously seeking a parent-type ally during those difficult early days at university, when fear and loneliness were issues.

She wasn’t saying there was anything false about her feelings, but on reflection it still seemed very early – she’d only recently turned twenty – for a commitment like marriage. By modern standards that was astonishingly young.

And will the parish church of Norwood Lee really help with any of this?

It now stood directly in front of her and didn’t look much different from other rural churches, except for being older and more weathered than most, and for the snow overhanging its roofs and the spears of ice descending from its eaves. As the leafless trees parted, and they emerged onto flat ground where ancient headstones jutted from the snow like black badly-angled teeth, Kay forcibly reminded herself that this was just a silly old tradition, that her curiosity about it sprang from her interests in the odd and esoteric, that she wasn’t taking it seriously.

Marsha gazed at the leaning gravestones and then up the towering edifice, its tall stained-glass windows blacked out by the icy darkness behind them. “Where’s a Hammer Horror film crew when you need one?” “Didn’t think it was going to be this big,” Kay admitted. “Didn’t Miss Jennings say it was small.”

“I think she meant it was small by parish church standards, which it probably is.”

“Why have something like this in a village the size of Norwood Lee?”

“It was probably paid for by that character who’s lying in the vault … what’s his name?”

“Henry Wilcote.”

“Yeah. Speaking of which—” Marsha looked at her phone “—it’s ten to midnight, so if we’re going to do this daft thing we’d better get on with it.”

A small part of Kay felt a twinge of unease. Perhaps, now that they were actually here, she’d been subconsciously hoping they’d have run out of time, but she nodded all the same.

They didn’t have a compass but circumnavigated the building on the basis it would have been built facing east, which meant that the main entry doors would be at the western end. From there, it was easy to deduce which side was south, and indeed when they crunched their way around there along a side-path shin-deep in banked-up snow they encountered two doors standing ten yards apart. The one on the left looked like a relatively recent addition, but the one on the right was made from older semi-perished wood filled with flattened nail-heads. What was more, that one stood ajar by a couple of inches.

“There’s an invitation if ever I’ve seen one,” Marsha said in a voice that was more cheerful than Kay thought the circumstances warranted.

For some reason, a dead chill now ran through Kay that had nothing to do with the temperature.

“Five minutes left,” Marsha said. “Are we going down?”

“Erm, yeah … sure.”

“Before we do, there is, perhaps … something.”

Kay glanced up, surprised at the querulous note in Marsha’s voice, and even more surprised to see the moonlight reflecting from a face suddenly taut with foreboding.

“Supposing,” Marsha said. “Just supposing … well, imagine that this ritual works. And we look round, and each of us … we see someone else? I mean not each other?”

“Oh.” Kay didn’t want to give away that this was precisely her own fear, but at the same time she didn’t want to dismiss it either, because maybe if they both felt this way it would be easier now to just turn around and walk in the other direction.

“I’m joking, you dipstick!” Marsha cackled.

“Oh, right. Yeah … sure.” Kay tried to smile. “What a shock it’d be.”

Marsha pushed at the door which swung open on silent hinges. Beyond it, when she turned her phone-light on, they saw a stone stairway falling into blackness. “After you,” she said.

“You know…” Unavoidably, Kay hesitated. “Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea.”

Marsha frowned. “You marched me all the way up here and now you want to march me all the way back without us at least setting eyes on this mysterious medieval warlock?”

“If you just want to look at his tomb we can come back tomorrow.”

“We’re here now. And it’s nothing to do with what I want. So, after you.”

Teeth gritted, Kay commenced a slow cautious descent. It was a narrow stairway, very much something she’d have expected from the Middle Ages, the rugged ceiling arching just above her head, the stone walls to either side crumbling and covered with moss. Her vaporous breath filled the tight space, white phantasms curling in the bright glow of her phone-light. When they reached the bottom, Kay at the front, Marsha behind, a gate stood in front of them set with corroded iron bars. And it appeared to be closed.

“Looks like we can’t go any further,” Kay said.

Marsha leaned past her, gripped one of the bars and pushed. With a grating and groaning, the gate opened. “That old biddy was right about one thing. This place is completely insecure.”

With no option, Kay ventured forward, phone held rigidly in front. The floor was paved and dry, but the actual dimensions of the place difficult to judge.

Kay slithered to a halt. And flinched when Marsha’s hand landed on her shoulder.

“Bloody hell,” Marsha chuckled. “You’re really jumpy.”

“I’m just cold…”

“It’s only another of those crusader tomb-type things. You’ve probably seen one in every cathedral you’ve ever visited.”

“Yes, but Marsha … we were told not to come here.”

“By someone who’s three sheets to the wind. Look, babe, you’re the one who wanted…”

“I know, but isn’t it…?”

“Hey, we don’t have to do it.” Somewhat belatedly, Marsha had latched onto the fact that Kay was quite nervous. She held up to two flat palms to indicate that they didn’t need to proceed, though the gesture was underscored with amusement implying that she still thought it a load of hogwash. “Won’t it give you a great blogpost, though? Your very own Christmas ghost experience?”

As if to illustrate, she strode along the left side of the tomb, phone clicking as she took photographs. Encouraged a little by this, and agreeing that yes, it would be an excellent post for her blog on Christmas morning, Kay shuffled closer, though even that slight movement echoed eerily, the mobile-light sources playing visual tricks in the deeper recesses of the undercroft.

Now that she was right up to him, Sir Henry Wilcote and his wife, Abigail, were much as Miss Jenkins had described them: smooth, featureless travesties of the detailed sculptures they’d once been.

“Wonder if their actual bones are lying under here?” Kay said, peering at the timeworn faces, only vaguely definable bumps and contours hinting at the eyes, mouths and noses.

“Presume so,” Marsha replied. “Otherwise, why would this place have any alleged magical power? They kind of lucked in, don’t you think?” She walked around the stone effigies until she was back where she’d started. “They weren’t just together all their lives, they’ve been together ever since. What was it … the Wars of the Roses? That’s nearly five-hundred years, yeah? These two were right for each other at least, even if they mucked about in the black arts to ensure it lasted. Anyway—” she checked the time “—we’ve got one minute, babe. Are we doing this thing, or what?”

“Suppose so.” Kay tugged off her left glove and stuck her hand into her anorak pocket where she’d stored a fistful of the high-health granola.

The Wilcotes’ long-lasting fidelity was surely some kind of indication that it was possible for people to remain loyal life-partners from an early age. Even in turbulent times. How old would Abigail Wilcote have been? Back in the Middle Ages didn’t girls get married as young as twelve or thirteen? And yet here she was in 2018, still lying alongside her husband.

“Let’s just do it,” she said, suddenly feeling energized by that. “After all, it’s better to know than not to know.”

Marsha held out her gloved palm so that Kay could sprinkle some grains into it, but arched a curious eyebrow. “You’re not really buying into this, are you? I mean, not seriously?”

“Like you say, let’s just do it.” Kay positioned herself so that they faced each other directly. “Now, do as I do…” And she threw the handful of grain over her left shoulder.

“Babe, whoa.” If you’re … look, maybe this isn’t such a good…”

“Please, Marsha!” Now that they’d started Kay was eager to see it through.

Defeated but bemused, Marsha tossed her own seeds backward.

Kay remained focussed. “Now repeat after me…”

“Whoa, you’ve memorised those lines? The old bat only said them once.”

“I only remember vaguely but I’m sure it’s the thought that counts…”

“Kay, listen…”

“‘Hemp-seed I scatter’ – come on, Marsha, you’ve got to say it.”

Reluctantly, Marsha said, “‘Hemp-seed I scatter.’”

“‘Hemp-seed I sew’—”

“Kay, this is—”

“Come on, please!”

Marsha shrugged exasperatedly. “‘Hemp-seed I sew.’”

“‘Let my true love come after me and mow.’”

“For Christ’s sake!”

“Marsha!”

“‘Let my true love come after me and mow.’”

Kay nodded, compressing her lips into a tight tense smile. Briefly, the silence in the crypt seemed to thunder in their ears. The friends regarded each other fixedly. And then Marsha jolted, her head jerking part-way around as though in surprise.

“What is it?” Kay asked, her pulse immediately racing. Almost as an afterthought she turned to glance over her own shoulder.

Marsha had heard something: a hollow wooden thud. Initially it had sounded like a door closing. As she’d glanced around she’d expected to see a priest or vicar, or some other custodian of the church who’d just emerged from another part of the cellar. That would have been difficult enough.

But this…

Her mouth slackened open, her eyes bugging in a face rapidly draining white.

“This … it’s a trick…” she said hoarsely, backing away until she collided with Kay, half-knocking her sideways. Kay turned and tried to grapple with her to prevent them both falling over but Marsha was rigid, a virtual stone. “It’s a damn trick!” she hissed again, staring at what to Kay looked like empty darkness.

“What is it?” Kay attempted to put arms around her. “What did you see?”

Marsha tore loose and backed frothy-lipped towards the iron gate. She pointed a shaking finger. “You … you had something to do with this. You must have. No one else could’ve—”

Kay held her hands out. “What is it? Just tell me.”

“It’s a damn trick! That’s all it can be! And a bloody nasty one!”

Marsha turned and blundered up the stairway.

“Wait!” Kay yelled, more confused than frightened, though that confusion lent wings to her heels as she stumbled up the steps in pursuit.

Marsha was the athlete, of course. When Kay reached the surface world there was already no sign of her friend, but there was only one way she could have run. Increasingly bewildered, Kay hastened along the side of the church. When she reached the end of the building she halted, lungs heaving, sweat chilling on her brow. From the chopped-up snow it appeared that Marsha had descended the hill the same way they’d come up here: down through the graveyard and along the lychgate path.

As Kay went that way too she spotted her partner’s lurching shape some fifty yards ahead.

“What in God’s name?” she stuttered as she ran. “Marsha! Marsha, wait!”

She finally got to the sloping road, sliding out through the gate and falling full-length on the pavement. The snow cushioned the impact but from here it was much more difficult: downhill and a smoother surface, her feet repeatedly skating from under her. Marsha was having similar problems and was now only thirty yards ahead. She too fell repeatedly and heavily until by the time she was at the bottom of the hill she was limping.

“Marsha!” Kay called again. “Wait, please!”

Marsha at last came down to the little-used road on the outskirts of the village. This area was street-lit, and perhaps feeling she’d returned to some version of civilisation and sanity, she turned around, her face flushed and soaked with sweat, though perhaps soaked with something else too – tears?

Kay was incredulous, never having once known Marsha to cry.

“What happened?” she asked, approaching with arms outspread. “For Heaven’s sake!”

“Don’t come near me, Kay.” Marsha retreated steadily. “If you didn’t know about that … well, it doesn’t matter because I know you didn’t. It know it couldn’t have been you. And if that’s the case I don’t like to think … I can’t even imagine…”

She stumbled off a kerb that was hidden in snow but continued to backtrack.

“So, you did see something?” Involuntarily, Kay’s own advance faltered.

Marsha shook her head, perplexed, baffled, tormented. “I just … I can’t believe it. I turned my head … and it was there. Right behind me. Only for a second, but—”

“What was there?”

“It was standing upright. Like a joke, like someone had put it there…” Fresh tears brimmed from Marsha’s eyes. “But I know that nobody did.”

“What? What was it?”

“For God’s sake, Kay … I saw a coffin.”

Kay’s blood iced over as she stopped in her tracks. She was still on the pavement, of course. But Marsha, unwittingly, had retreated into the very middle of that little-used road.

Little-used, but not unused – as a sudden screech of brakes and squealing of tyres attested. The van, which had come around the corner at reckless speed, went careering out of control, its wheels locking on the frozen surface.

Kay shouted hysterically but it was too late.

The impact was shattering, the detonation reverberating across the sleeping village.

Within a couple of minutes people were emerging from the nearest houses, wearing coats over their pyjamas and wellingtons instead of slippers. A short time later an ambulance arrived, followed almost immediately by a Thames Valley police car. Questions were fired around as people stood dumbfounded in the cold.

Kay watched it all from a sitting position on the kerbstone, through a bur of tears and clawed fingers. She barely spoke, scarcely aware of the hot tea and blankets offered by concerned villagers. She voiced no opinion, as the van driver, who was incoherent – whether that was through shock or drink or both was unclear – was taken away in handcuffs. She literally lost track of time as the haze of spinning blue lights slowly mesmerised her.

“Excuse me but I must ask you this … what happened?”

Kay could barely respond though she was aware the question had come from a police officer, a sergeant by the stripes on the epaulettes on her hi-vis, waterproof overcoat.

“I’m sorry, I don’t know who you are yet,” the policewoman persisted. “But perhaps you can tell me … did you see anything?”

Kay looked up at that, the policewoman blanching at the depths of horror and misery etched into her face.

“I’m sorry,” the officer said. “But I need to know … what did you see?”

Kay directed her gaze back across the road, thoughts straying to that frigid pit beneath the church – but her eyes fixed on the large black bag, heavy and cumbersome and zipped securely up one side, that the undertakers were manhandling into the back of their hearse.

“Nothing,” she said in a voice of utter bleakness. “I saw nothing at all.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)