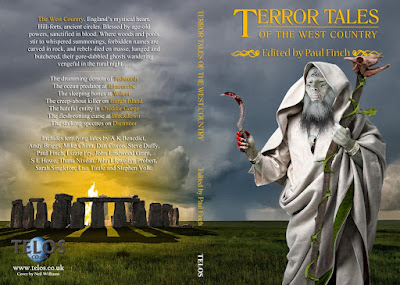

The season of mist is definitely upon us. So, it’s probably a very good time to talk about the next volume in the TERROR TALES series, which, as you can see here, is TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY.

Okay, I know you’ve all been waiting for this one. And don’t worry; if you always associate the West Country with sunshine, hay riggs and the green fields of summer, and now, all of a sudden, we’re into the realm of darkness, falling leaves and jack-o-lanterns, be assured that facades can be deceptive. There is an awful lot of spookiness going on in the West Country, and especially in this new anthology.

Just keep reading for the full Table of Contents, the back-cover blurb, a few choice snippets from selected stories, and full details of how you can pre-order HERE.

In addition to that treat, and fully in keeping with the fact that Lisa Tuttle, that British queen of the mysterious macabre, makes her debut in this volume in the series, I’ll also be reviewing her exceptional novel, THE MYSTERIES, a wonderful work of folk-horror in its own right.

If you’re only here for the review of Lisa’s book, you’ll find that, as always, in the Thrillers, Chillers section at the lower end of today’s blogpost.

Before that though, let’s get into …

This is of course the latest in a long line of regional folklore-inspired horror anthologies that I’ve edited (firstly for Gray Friar Press, but this time and for the last several in fact with TELOS PUBLISHING), all stemming from my lifelong fascination with ghost and horror stories, regional lore and folk-mysteries, and the most ancient and unexplained aspects of Britain’s landscape and culture.

If you want to check out the other books in the series so far, go HERE. If you want to proceed with this one, let’s get on with this …

The West Country. England’s mystical heart. Hill-forts, ancient circles. Blessed by age-old powers, sanctified in blood. Where woods and pools stir to whispered summonings, forbidden names are carved in rock, and rebels died en masse, hanged and butchered, their gore-dabbled ghosts wandering vengeful in the rural night …

The drumming demon of Tedworth

The ocean predator at Ilfracombe

The sleeping bones at Wilcot

The creep-about killer on Burgh Island

The hateful entity in Cheddar Gorge

The flesh-rotting curse at Blackdown

The stalking spectres on Dartmoor

Includes terrifying stories by AK Benedict, Andy Briggs, Mike Chinn, Adrian Cole, Dan Coxon, Steve Duffy, Paul Finch, Lizzy Fry, John Linwood Grant, SL Howe, Thana Niveau, John Llewellyn Probert, Sarah Singleton, Lisa Tuttle and Stephen Volk.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Darkness Below by Dan Coxon

Unto These Ancient Stones

Objects in Dreams May Be Closer Than They Appear by Lisa Tuttle

The Horror at Littlecote

The Woden Jug by John Lindwood Grant

And Then There Was One

Chalk and Flint by Sarah Singleton

When Evil Walked Among Them

Epiphyte by Thana Niveau

The Hangman’s Pleasure

In the Land of Thunder by Adrian Cole

The Thing in the Water

Unrecovered by Stephen Volk

Priests of Good and Evil

Gwen by SL Howe

The Pixie’s Curse

Watcher of the Skies by Mike Chinn

Vixiana

Bullbeggar Walk by Paul Finch

The Tedworth Drummer

The Pale Man by Andy Briggs

By the Axe, He Lived

Little Down Barton by Lizzie Fry

Hounds of Hell

Certain Death for a Known Person by Steve Duffy

The Blood Price

Knyfesmyths’ Steps by AK Benedict

Lonesome Roads

Soon, the Darkness by John Llewellyn Probert

And if that didn’t wet your whistles sufficiently, here are several uber-discomforting excerpts.

The old moss woman stepped out from the side of the lane and stood in front of her. Still in threadbare wintery apparel, she was all rotten wood bones beneath the lush moss cloak. Her hair was long and white, bedraggled strands of last year’s grass around a face of dark, yawning gaps and hollows …

Sarah Singleton – Chalk and Flint

‘What are you getting at?’ For the first time since my arrival at High Thornhays I was on the defensive. Old habits born of inadequacy coming to the fore; truculence, sullenness … and just the beginnings of fear. The man with no face there in the armchair: I was already afraid of him. Not nearly as afraid as I ought to have been, not yet. But soon; very soon.

Steve Duffy – Certain Death for a Known Person

Holes had been poked for eye sockets. The blackened lumps of something moist that had been pushed deep within the ragged cavities now regarded him soullessly. It was the kind of weird nonsensical thing that under normal circumstances would be funny but here, in this desolate place, with the chill and the damp worming their way between the folds of his clothes, the idea of some mutant horse-thing hobbling across the landscape on its hind legs wasn’t remotely amusing.

John Llewellyn Probert – Soon, the Darkness

The TERROR TALES series is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me throughout my time in dark fiction. I’ve derived limitless pleasure from working alongside and becoming very friendly with a vast number of immensely talented authors from a range of disciplines (crime, thriller and historical as well as horror and fantasy), almost all of whom (with only one or two rare exceptions), have totally bought into what I’ve tried to do with these books, and have given it their very best shot. With luck, there are lots more titles in the barrel yet, and many, many more writers for me to invite to participate.

But in the meantime, everything is focussed on TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY, which will be published around Halloween but which you can pre-order RIGHT NOW.

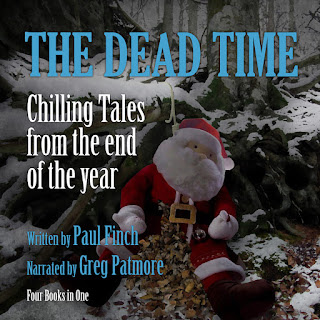

Before we get to today’s book review, a quick reminder about THE DEAD TIME.

But in the meantime, everything is focussed on TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY, which will be published around Halloween but which you can pre-order RIGHT NOW.

*

Before we get to today’s book review, a quick reminder about THE DEAD TIME.

This is an all-in-one collection of four of my books, each one related to a different scary aspect of the waning year, and it can be purchased now on Kindle or Audible RIGHT HERE.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

*

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

by Lisa Tuttle (2005)

Outline

We open with Ian Kennedy, an ex-pat American living in London who just about earns a living as a private eye, his speciality pursuing and finding missing persons. A tricky way to make ends meet, you might think, but this vocation is pretty much hardwired into him thanks to a series of incidents in his past during which loved ones dropped out of sight.

For example, one day when he was a child, during a family daytrip, Kennedy’s father disappeared right in front of his eyes. In later years, when he was living happily with girl-of-his-dreams, Jenny, she too vanished, simply winked out of existence just when he thought they couldn’t have been happier together. In both cases, these seemingly unaccountable mysteries were resolved by Kennedy when he finally got his investigator head on, and in truth, and perhaps sadly, there were no extraordinary circumstances: it was all very mundane and centred around selfishness and sex.

However, both disappearances made such an impression on Kennedy that they set him on a course in life he has never rejected since, so much so that he’s become very good at finding missing people. He’s also become very open-minded, because one of his earliest commissions sent him up into the Scottish Highlands, where, amid the mist and pine-trees, he found himself on the trail of a young woman who might have been abducted into the ‘Other World’ … and that would be the real Otherworld, the hidden land of mysterious spirits once known as faeries.

It all may sound implausible, as fantastical a memory as the delusion Kennedy lived under that his father had dropped out of this world through some kind of dimension door when in reality all he’d done was move in with his mistress, but rushing back to the present day, we now find Kennedy recruited by another American living in London, the attractive and wealthy Laura Lensky, whose daughter, Peri, also vanished during a bizarre and inexplicable occurrence.

This was two years ago, and the police have never really been interested. To them, Peri was an adult and adults can drop out of sight if they wish, and this seems especially likely when there is no evidence at all of foul play. However, Peri’s posh ex-boyfriend, Hugh Bell-Rivers, a guy who, to all intents and purposes, has now moved on with his life and even has another girlfriend, tells a different story.

He struggles to recollect criminal activity, but still recalls a chilling event, explaining how he and Peri attended an eerie nightclub in the heart of London (in a tremendously skin-prickling scene), where they met a handsome, charismatic stranger called Mider, who seemed to be particularly taken by Peri, while she, in turn, was semi-entranced by him, and how, even though Peri was later delivered safely home by Hugh, she went missing the following day, and when he went back to the nightclub, it was no longer there.

Any ordinary PI might take such a story with a pinch of salt, working on the basis of drugs or too much drink, and respond in the same indifferent way the police did. But Kennedy has been around. He’s heard about Mider before, too. The guy is a legend. Literally. A renowned seducer and abductor of women, but he is only supposed to exist in Celtic mythology …

Review

Lisa Tuttle’s The Mysteries is a strange kind of beast. Sitting triangulated somewhere between horror, thriller and fantasy, it packs a unique punch, asking all sorts of questions about the human condition, how our hopes and fears can affect our perceptions of reality, how loss and betrayal can permeate through the rest of our lives, changing us completely, sending us in totally different directions, but at the same time it hits us with an intriguing and suspense-filled mystery, which, from the very beginning has a possible supernatural explanation (which I personally thought made it all the more enthralling).

Of course, mystery lies at the core of this story. Even between chapters, Lisa Tuttle treats us to short, skillfully-told anecdotes about famous disappearances in history, some of which were later resolved, but many of which, most of them in fact, are rumoured to have been the work of the faeries, a race of enigmatic beings who, in mythology, had nothing to do with Victorian nursery books but were the occupants of an alternate world to ours, whose moods and motivations were completely unknowable to humans, and yet who were so fascinated by mortals that they would regularly cross over and take them captive.

We hear about Corporal Armando Valdes Garrido of the Chilean Army, who in 1977 disappeared in front of his men, only to reappear fifteen minutes later, unable to explain where he had been and yet sporting a five-day growth of beard. And Eliduras, the 12th century priest who was tortured for the rest of his days by childhood memories of entering a wondrous land through a portal under a tree, which he was never again able to find. And even the famed quartet of lighthouse keepers, Joseph Moore, James Ducat, Donald McArthur and Thomas Marshall, who in 1899 vanished from the remote Eilean Mor lighthouse without explanation or trace.

All of this is counterbalanced to a degree by the prosaic solutions provided for the disappearances of Ian Kennedy’s father and later on his girlfriend, Jenny Macedo. Not that these aren’t also mysterious events in their own way, or compellingly handled by the author (as well as showing great emotional depth). A couple of reviewers have criticised the otherwordly elements in The Mysteries, pointing out that Fairyland, for want of a better term, if it exists at all, is supposed to be unreachable by humans and that Ian Kennedy, though he’s already overcome the immense obstacle of not knowing whether to believe in it or not, makes contact with this curious realm far too easily. My response to that would be that Lisa Tuttle is only reflecting the many myths of Britain and Ireland, wherein ordinary, everyday people unintentionally blunder into this fantastical place, or at least make contact with its denizens by accident (unless those denizens themselves want it to happen, in which case those ‘accidents’ can easily be engineered).

Another argument presented by naysayers is that it’s all too implausible and that, in The Mysteries, we are simply asked to believe the unbelievable, namely that the Otherworld is real, and that magical beings known as the Fae, or the Faerie, or fairies, genuinely exist, and that everyone in this narrative buys into it far too quickly, which is all the more odd given that Ian Kennedy is supposed to be a private investigator, the sort of hardnosed bloodhound who would normally be chasing wanton wives and absentee husbands. But again, there’s an answer. If you want a hardboiled detective story set in the world of Noir, don’t read The Mysteries. Likewise, if you want a police procedural or an actioner, go somewhere else.

As I’ve already said, from its outset, this novel makes it clear that we are on the edge of a fantasy kingdom, and this despite the down-to-Earth elements of Kennedy’s father’s callous abandonment of his family, Jenny Macedo’s unfaithfulness, and even the cold, rain-wet London streets where our hero spends most of his time.

If because of this, you are only half-and-half on whether or not to read The Mysteries, I would urge you to proceed. Because the real joy of this book is Lisa Tuttle’s writing style. It’s very smooth and hugely accessible, everything clipped down to its crisp basics but penned with a real flourish so that it’s a pleasure simply to read it, the pages flipping by effortlessly. In addition to that, though it’s not a complex mystery (not by other PI novel standards), the overarching story that The Mysteries seeks to tell could be overly complex if it wasn’t for the masterful way that Tuttle constructs it. The various events of Ian Kennedy’s life, not just his own odd experiences as a young man back in the States, but his first investigation up in Scotland (the one that persuaded him there are more things in Heaven and Earth), and then the main one, the pursuit of Peri Lensky, run in parallel strands, which are timed to perfection and complement each other marvellously.

All in all, The Mysteries is a thoroughly engaging and entertaining read: a fantasy, yes, but without the extreme aspects of that genre that some readers might find offputting; a thriller too, but without the terror and violence and blood (though this doesn’t mean there aren’t some intense moments of creeping dread – oh yes, there is evil afoot, even in Fairyland).

I stumbled upon this book by accident, and I’m really glad I did. In The Mysteries, Lisa Tuttle has given us a very different, very sophisticated but, above all, very enjoyable kind of mystery. I recommend that you avail yourself of it right away.

I’m now going to commit my usual folly of attempting to cast this piece before someone out there in film or TV land gets smart enough to do it for real. Just a bit of fun, of course, but here’s who I’d use:

Ian Kennedy – Tom Payne

Laura Lensky – Amy Adams

Hugh Bell-Rivers – Dean-Charles Chapman

Mider – Claes Bang

Jenny Macedo – Ruth Negga

Fred Green – Elizabeth Debicki

Outline

We open with Ian Kennedy, an ex-pat American living in London who just about earns a living as a private eye, his speciality pursuing and finding missing persons. A tricky way to make ends meet, you might think, but this vocation is pretty much hardwired into him thanks to a series of incidents in his past during which loved ones dropped out of sight.

For example, one day when he was a child, during a family daytrip, Kennedy’s father disappeared right in front of his eyes. In later years, when he was living happily with girl-of-his-dreams, Jenny, she too vanished, simply winked out of existence just when he thought they couldn’t have been happier together. In both cases, these seemingly unaccountable mysteries were resolved by Kennedy when he finally got his investigator head on, and in truth, and perhaps sadly, there were no extraordinary circumstances: it was all very mundane and centred around selfishness and sex.

However, both disappearances made such an impression on Kennedy that they set him on a course in life he has never rejected since, so much so that he’s become very good at finding missing people. He’s also become very open-minded, because one of his earliest commissions sent him up into the Scottish Highlands, where, amid the mist and pine-trees, he found himself on the trail of a young woman who might have been abducted into the ‘Other World’ … and that would be the real Otherworld, the hidden land of mysterious spirits once known as faeries.

It all may sound implausible, as fantastical a memory as the delusion Kennedy lived under that his father had dropped out of this world through some kind of dimension door when in reality all he’d done was move in with his mistress, but rushing back to the present day, we now find Kennedy recruited by another American living in London, the attractive and wealthy Laura Lensky, whose daughter, Peri, also vanished during a bizarre and inexplicable occurrence.

This was two years ago, and the police have never really been interested. To them, Peri was an adult and adults can drop out of sight if they wish, and this seems especially likely when there is no evidence at all of foul play. However, Peri’s posh ex-boyfriend, Hugh Bell-Rivers, a guy who, to all intents and purposes, has now moved on with his life and even has another girlfriend, tells a different story.

He struggles to recollect criminal activity, but still recalls a chilling event, explaining how he and Peri attended an eerie nightclub in the heart of London (in a tremendously skin-prickling scene), where they met a handsome, charismatic stranger called Mider, who seemed to be particularly taken by Peri, while she, in turn, was semi-entranced by him, and how, even though Peri was later delivered safely home by Hugh, she went missing the following day, and when he went back to the nightclub, it was no longer there.

Any ordinary PI might take such a story with a pinch of salt, working on the basis of drugs or too much drink, and respond in the same indifferent way the police did. But Kennedy has been around. He’s heard about Mider before, too. The guy is a legend. Literally. A renowned seducer and abductor of women, but he is only supposed to exist in Celtic mythology …

Review

Lisa Tuttle’s The Mysteries is a strange kind of beast. Sitting triangulated somewhere between horror, thriller and fantasy, it packs a unique punch, asking all sorts of questions about the human condition, how our hopes and fears can affect our perceptions of reality, how loss and betrayal can permeate through the rest of our lives, changing us completely, sending us in totally different directions, but at the same time it hits us with an intriguing and suspense-filled mystery, which, from the very beginning has a possible supernatural explanation (which I personally thought made it all the more enthralling).

Of course, mystery lies at the core of this story. Even between chapters, Lisa Tuttle treats us to short, skillfully-told anecdotes about famous disappearances in history, some of which were later resolved, but many of which, most of them in fact, are rumoured to have been the work of the faeries, a race of enigmatic beings who, in mythology, had nothing to do with Victorian nursery books but were the occupants of an alternate world to ours, whose moods and motivations were completely unknowable to humans, and yet who were so fascinated by mortals that they would regularly cross over and take them captive.

We hear about Corporal Armando Valdes Garrido of the Chilean Army, who in 1977 disappeared in front of his men, only to reappear fifteen minutes later, unable to explain where he had been and yet sporting a five-day growth of beard. And Eliduras, the 12th century priest who was tortured for the rest of his days by childhood memories of entering a wondrous land through a portal under a tree, which he was never again able to find. And even the famed quartet of lighthouse keepers, Joseph Moore, James Ducat, Donald McArthur and Thomas Marshall, who in 1899 vanished from the remote Eilean Mor lighthouse without explanation or trace.

All of this is counterbalanced to a degree by the prosaic solutions provided for the disappearances of Ian Kennedy’s father and later on his girlfriend, Jenny Macedo. Not that these aren’t also mysterious events in their own way, or compellingly handled by the author (as well as showing great emotional depth). A couple of reviewers have criticised the otherwordly elements in The Mysteries, pointing out that Fairyland, for want of a better term, if it exists at all, is supposed to be unreachable by humans and that Ian Kennedy, though he’s already overcome the immense obstacle of not knowing whether to believe in it or not, makes contact with this curious realm far too easily. My response to that would be that Lisa Tuttle is only reflecting the many myths of Britain and Ireland, wherein ordinary, everyday people unintentionally blunder into this fantastical place, or at least make contact with its denizens by accident (unless those denizens themselves want it to happen, in which case those ‘accidents’ can easily be engineered).

Another argument presented by naysayers is that it’s all too implausible and that, in The Mysteries, we are simply asked to believe the unbelievable, namely that the Otherworld is real, and that magical beings known as the Fae, or the Faerie, or fairies, genuinely exist, and that everyone in this narrative buys into it far too quickly, which is all the more odd given that Ian Kennedy is supposed to be a private investigator, the sort of hardnosed bloodhound who would normally be chasing wanton wives and absentee husbands. But again, there’s an answer. If you want a hardboiled detective story set in the world of Noir, don’t read The Mysteries. Likewise, if you want a police procedural or an actioner, go somewhere else.

As I’ve already said, from its outset, this novel makes it clear that we are on the edge of a fantasy kingdom, and this despite the down-to-Earth elements of Kennedy’s father’s callous abandonment of his family, Jenny Macedo’s unfaithfulness, and even the cold, rain-wet London streets where our hero spends most of his time.

If because of this, you are only half-and-half on whether or not to read The Mysteries, I would urge you to proceed. Because the real joy of this book is Lisa Tuttle’s writing style. It’s very smooth and hugely accessible, everything clipped down to its crisp basics but penned with a real flourish so that it’s a pleasure simply to read it, the pages flipping by effortlessly. In addition to that, though it’s not a complex mystery (not by other PI novel standards), the overarching story that The Mysteries seeks to tell could be overly complex if it wasn’t for the masterful way that Tuttle constructs it. The various events of Ian Kennedy’s life, not just his own odd experiences as a young man back in the States, but his first investigation up in Scotland (the one that persuaded him there are more things in Heaven and Earth), and then the main one, the pursuit of Peri Lensky, run in parallel strands, which are timed to perfection and complement each other marvellously.

All in all, The Mysteries is a thoroughly engaging and entertaining read: a fantasy, yes, but without the extreme aspects of that genre that some readers might find offputting; a thriller too, but without the terror and violence and blood (though this doesn’t mean there aren’t some intense moments of creeping dread – oh yes, there is evil afoot, even in Fairyland).

I stumbled upon this book by accident, and I’m really glad I did. In The Mysteries, Lisa Tuttle has given us a very different, very sophisticated but, above all, very enjoyable kind of mystery. I recommend that you avail yourself of it right away.

I’m now going to commit my usual folly of attempting to cast this piece before someone out there in film or TV land gets smart enough to do it for real. Just a bit of fun, of course, but here’s who I’d use:

Ian Kennedy – Tom Payne

Laura Lensky – Amy Adams

Hugh Bell-Rivers – Dean-Charles Chapman

Mider – Claes Bang

Jenny Macedo – Ruth Negga

Fred Green – Elizabeth Debicki